Review by Frank Plowright

At first reckoning it may not seem that a rambling gothic novel written by an exiled Victor Hugo in the Channel Isles during his dotage in the mid-Victorian era would have much relevance to 21st century Britain. Hugo’s core strengths, though, were his talents as a consummate storyteller and his unflagging compulsion to highlight the plight of those without a voice of their own, the downtrodden and dispossessed. Both are relevant today.

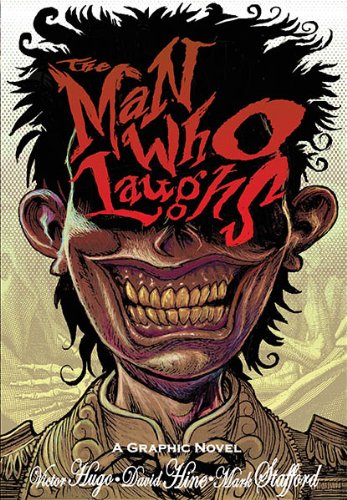

Adapter David Hine has carried out much of the hard work on our behalf, mining Hugo’s discursive narrative for the excellent plot at its core. We open with a mystery, then move to a shoeless young boy in the snow, Gwynplaine, who rescues a crying infant from its frozen mother’s corpse before chancing on the caravan of an erudite travelling entertainer. Ursus christens the baby Dea, and remarks that someone’s deformed Gwynplaine’s face, leaving him with a permanent grinning open mouth.

The trio pool their resources to form a travelling show mixing the cultural and the sideshow, arriving in London when both the children are young adults. From there we enter some very strange territory, and as the plot unwinds we learn of Gwynplaine’s mutilation, a manipulative servant and the callous nature of the upper classes. Hugo’s melodrama is frankly barking, but also thoroughly entertaining, with a central wild, unpredictable twist. Hine is faithful to the republican message integral to the plot, but notes in his afterword that much of the repetition was pruned.

Mark Stafford’s art is excellent in most respects, providing a sort of scratchy engraved woodcut look, but also problematical. He’s deliberately opted for a process that accentuates the grotesque, which works fine for Gwynplaine’s rictus grin, but when the text requires a woman of exceptional beauty the style only permits someone slightly less homely. Stafford is well up to conveying the seedy London of the era and some of Hugo’s more fanciful creations, such as the silent Wapentake, a foreboding official messenger with a distinctive hat and stick who must be followed when he summons. The path leads to court, and refusal to death. Also be sure not just flick past Stafford’s great chapter title illustrations, every one a t-shirt.

The afterword further notes that Conrad Veidt’s portrayal of Gwynplaine in the 1926 film adaptation was the visual inspiration for the Joker, so The Man Who Laughs has a connection leading all the way back to the earliest days of comics. Permit yourself to be sucked into the eccentricity and this is a rewarding adaptation.