Review by Ian Keogh

Reconfiguring Huckleberry Finn is an immediate challenge, not least that it’s often considered the greatest novel from an American writer, so tackling it alone invites comparison, never mind messing with it. Furthermore, in the 21st century it’s a problematical work. If the treatment of escaped slave Jim is kindly in some respects, it also encompasses the repeated use of the era’s racist language. Author David F. Walker, a Black writer, provides an introduction to his reworking explaining why the word “nigger” needs to remain in editions of the original work and why he’s used it.

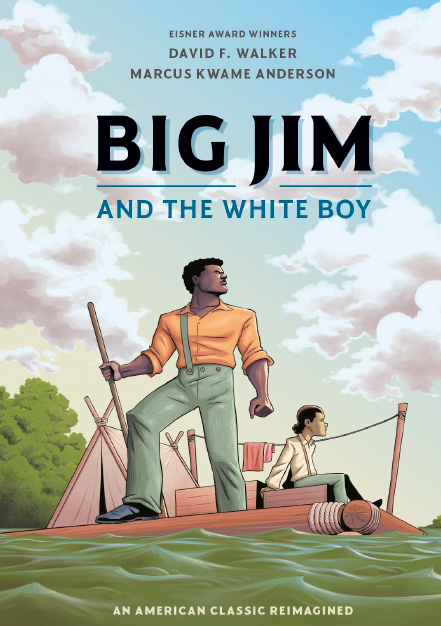

Walker picks up with Huckleberry and Jim already on the raft floating down the Mississippi river approaching a steamboat wreck, but almost immediately interrupts the narrative to jump to 1932 and Jim’s comments on events as related by Mark Twain before presenting Jim’s true version. Marcus Kwame Anderson alters the tone of the art to convey the accurate circumstances. Jim is no longer a reluctant cowering figure, but drawn as strong, confident and heroic. Almost an action hero, in fact.

It’s indicative of Walker initially telling the story while also inviting conversation about it and about what was socially acceptable at the time, with later scenes picturing lectures about Twain and his work. Walker delves deep, and in doing so inserts additional scenes humanising Jim in a way Twain didn’t. It’s illuminating. We also see Jim’s commentary comes from a lecture he’s giving, accompanied by Huckleberry, now also an old man. The White Boy in the title is an implant attributed to the name by which Joe Finn referred to his son.

Jim and Huckleberry as action heroes is a continuing theme, in one way a more realistic configuration of their relationship were they to remain together beyond the novel’s end. They rescue slaves and tackle injustice while avoiding capture. Here Anderson feeds in the layouts and cinema of action comics, down to mimicking the flat colour, speed lines and shading. His art throughout is well conceived and deliberately avoids complexity to best pass on the message to the young audience at whom this is aimed.

The deeper into Big Jim and the White Boy we travel, the more Walker’s introduction makes sense, and the further it departs from Twain’s novel to become a multi-generational saga, even involving elements from Walker’s family history. Unlike other well intentioned graphic novels, Walker cuts no corners in spelling out on a scale from indignity to horror just what life was like for an escaped slave, and why it was still preferable to servitude. A clever presence is an old Huckleberry arguing with an aged Jim about the truth of what happened roughly eighty years previously, which occurs as Walker returns to another of the novel’s pivotal sequences when Jim is captured.

There are a couple of mis-steps, one being the forced introduction of John Brown and through him the story of Nat Turner. It’s Walker having a captive audience and taking his opportunity to pass on as much as possible, which is brief, but intrusive. Another item that could have been considered more is just how much to bend toward the needs of narrative fiction. When a menace appears a third time, it’s once too many despite forcing a resolution. However, the bigger picture is more important.

Whether you look at Big Jim and the White Boy as a social study, a retelling adding depth and detail or an educational tool, it’s a resounding success.