Review by Ian Keogh

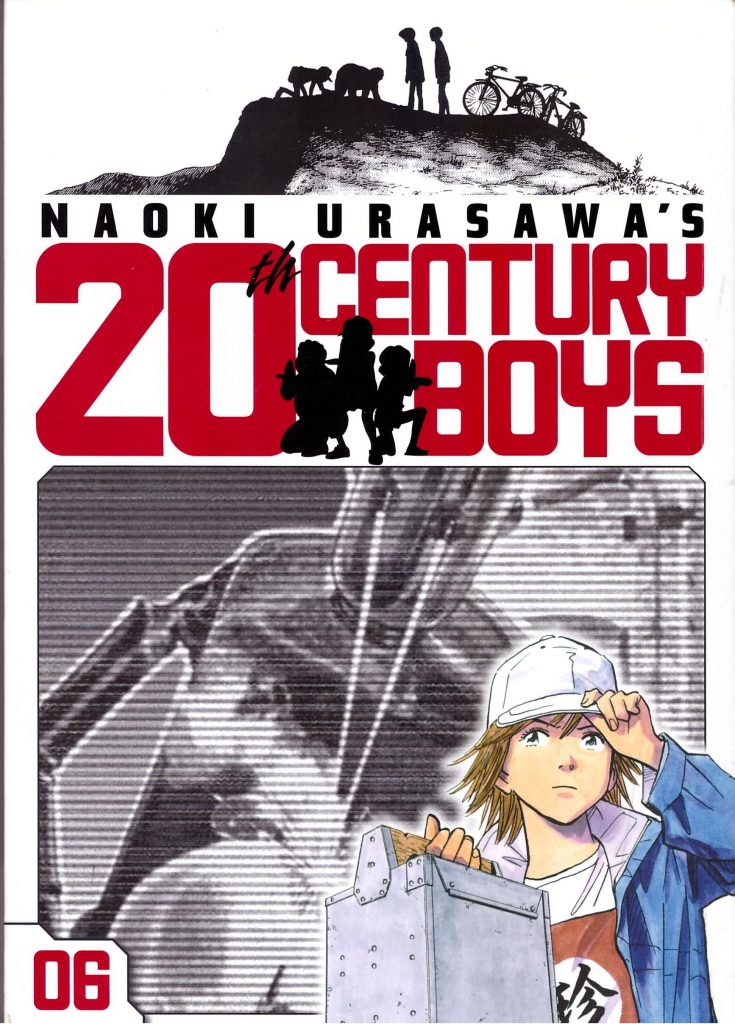

While a slightly lesser volume overall, Naoki Urasawa dropped one hell of a plot bombshell to end Reunion, completely pulling the rug from under what he’d led readers to believe when he began 20th Century Boys. It was a jaw dropping moment. That was after another real surprise in moving the story forward to 2014 with no real explanation of what happened on New Year’s Eve 2000. In the earlier books Kanna appeared as infant, but now she’s a rebellious seventeen and keeping her father’s musical legacy alive. Urasawa didn’t reveal what happened to him.

Along with the switch in time, Urasawa’s changed the idea of a consistent tone. Some horrific events occur in Final Hope, but there’s also a large role for naive police detective Chono, young and lacking the confidence to match his ambition and inspiration. Urasawa shows him as dedicated with sound instincts, but also uses him as a form of comedy relief easily intimidated by longer serving officers and the local community. It’s apparent his will be a persistent and productive part, but his subservience and awkwardness is almost irritating instead of sympathetic.

The Japan of 2014 has been shaped by what happened in 2000, and by all indications it’s a near totalitarian state. In Reunion Urasawa mentioned a manga artist arrested for unsuitable material, and what appeared a throwaway reference at the time actually has some relevance as we now meet him in jail. This series is one of constantly tight plotting and expert foreshadowing, with that just another example. At this point the manga artist isn’t important himself, but where he leads is very interesting. Eventually, so is where Chono leads, which is to a very chilling place for anyone who’s read volume 03, and it plays out as suitably disturbing.

Toward the end of the book there’s a discussion about the movie The Great Escape, the first visit back to the 1970s childhoods for some while. When shown on Japanese TV the movie was serialised over two parts and Urasawa has one of the cast throw out the theory that it was possible to tell who would escape in the second part due to the desire in their eyes. Only those who truly believed they’d escape actually would. It’s a theory carried over to the events of 2014 to iconic effect. And by the end of the book the manga artist has taken a more prominent role, but he seems well resourced, so is he a surprise in waiting? That’s the way Urasawa makes you think. His bombshells are so good he cultivates a suspicious mind among readers inclined to second guess him. Perhaps it’s best not to, and to just enjoy the ride.

Final Hope is very good mystery drama, and combined with the previous outing as Perfect Edition Volume 3. Urasawa presses all the right buttons with some first rate plotting, but for all that, in rebooting the series in 2014 he’s also lost something as he’s moved 20th Century Boys into more conventional territory. The mysteries are good, but it’s no longer a story about one person well beyond his depth standing up to an implacable enemy, filtered through with charming and funny childhood reminisces, and the lack of that contrast slightly diminishes the magic. The series continues with The Truth.