Review by Graham Johnstone

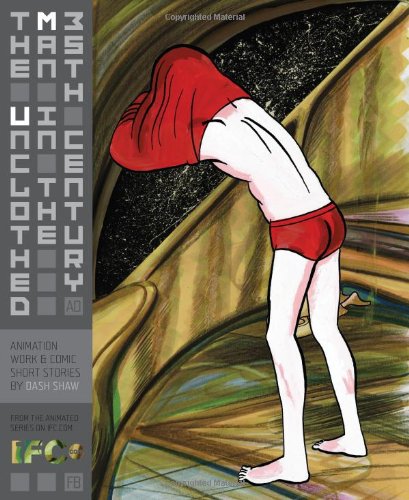

Dash Shaw impressed in the Mome anthology, also published by Fantagraphics. Only in his mid-twenties, he appeared fully-formed with his psychologically and formally dazzling shorts, collected here along with storyboards from animation work.

The pieces from Mome still astound. The first is an untitled story across two versions of earth, with time moving in opposite directions (pictured). Reverse chronology stories aren’t new, but Shaw uses the form for an exploration of the political and social, centring on the most ancient human connection, between a couple across worlds. His dismantled palette of primary colours adds coherence to his intercut scenes. Crammed into six pages, it’s intricate, and as humane as it is technical.

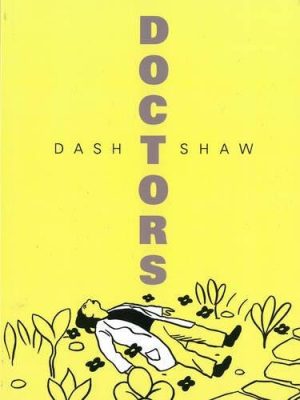

He mines similar territory with ‘Satellite CMYK’, with a futuristic premise of a society constructed on a series of levels, between which movement is forbidden. Rebels subvert this, taking people between levels and implanting them with fake memories into families of rebel moles. It’s such an elaborate set-up as to suggest that these rebels have become as caught up in their own machinery as the establishment they oppose. Again working over an anthology-friendly few pages, Shaw delivers a sharply plotted, multi-stranded story, ultimately about relationships, memory and loss – themes he’d explore at greater length in Doctors. The four ink colours alluded to in the title are used to distinguish different strands of the story. It’s visually appealing, though the text can be hard to read over the full strength colours. As characters move between layers, the colour concept is cleverly used, and Shaw delivers an ending that brilliantly pulls together the narrative and formal elements.

An untitled story is also set in the future, as a young artist tries to represent the never explained phenomenon of galactic funnels. At heart, it’s less about technology than society and individuals, in this case art tutor and pupil. Shaw intensifies the drama by making this a romantic relationship, and giving them overlapping art subjects and methods: raising issues of comparison, originality, and credit between the pair. Shaw’s art here is different again, introducing painted elements. There’s a slight queasiness to his purple and green palette, but mostly the mix of flat and painted rendering works, and it fits with the art style debates within the story. It’s further proof of Shaw’s impressive ability to integrate form and content, world-building and human relationships.

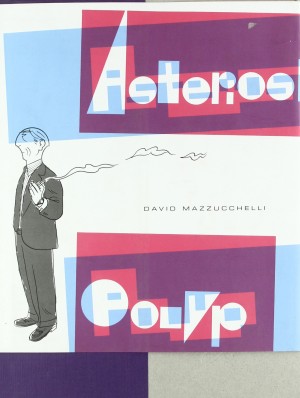

‘Cartoon Symbolia’ is an exploration of some of the abstract symbols and devices used in comics. Readers might deduce that Waftaroms convey smell. and Solrads light, but who knew about Plewds – ‘drop shapes indicating a discharge’? Shaw gives us convincing plewd variants for different types of sweating and tears. He credits Jack Kirby with Invisitides – the dotted lines denoting Invisible Girl, but there’s no mention of Mort Walker who coined many of the terms, and we’re left to guess where Shaw has quoted or invented. Staring with a list format, characters and a story emerge that confront such issues of creation and credit.

The few other comics all have interesting elements, but none satisfy like those above.

Shaw is assertive in presenting the storyboards as equal to the comics – beginning and ending the book with them. They show the same keen mind at work, but ultimately they’re just a working tool – the drawings often too cursory, and the regular panels and text boxes lacking the appeal of his well-designed comics pages. It feels like they are extras bulking out the book, but this is outweighed by the sheer dazzling brilliance packed into the comics pages.