Review by Frank Plowright

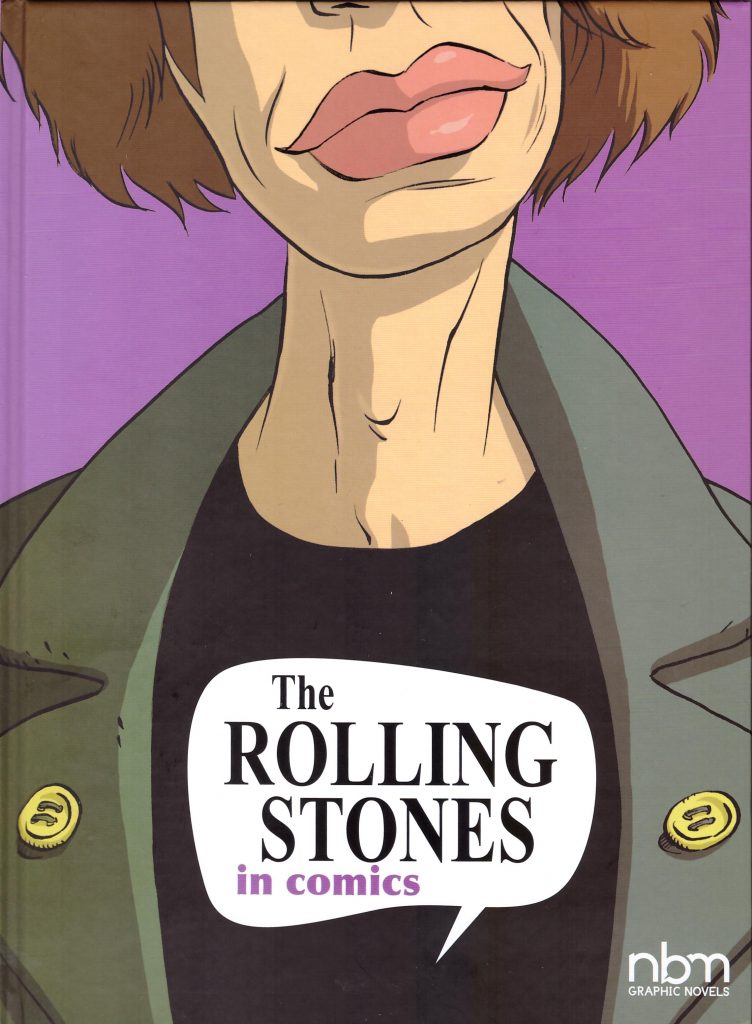

As was the case with their companion translated Beatles edition, NBM’s The Rolling Stones in Comics blends articles, profiles and photographs of what was once the world’s biggest rock band, with short comic strips detailing pivotal moments in the band’s history, 21 in total.

It’s a squarely aimed at feeding a voracious audience who’ll pick up any serious project about their idols. They’ll know most of the information, but seeing it interpreted in a new way is beguiling, and most of the comic strips work well, the assorted cartoonists devising some great caricatures of the band over the years. Each band member gets a spotlight, the content thorough enough to include Ian Stewart, and many pieces avoid the obvious. The importance of open tuning to the Stones sound is essential (but a weaker artistic effort from Patès), the story of Jagger’s first solo album by Sarah Williamson funny, and the Beatles writing I Wanna Be Your Man for the Stones by Domas stands out. Especially good is cover artist Bast’s piece juxtaposing Brian Jones’ death with an embarrassment from two years earlier.

For all the good strips, this is a very different package from the Beatles book, with shorter strips and far more text, and troublesome from the opening words. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ home town is described as a village, when the Dartford in which they grew up had a population well in excess of 50,000. The mistake is compounded by miscrediting the artist drawing their first meeting as “Marin” Trystam instead of Martin (as he was correctly for the Beatles book). It’s widely known that the band took their name on the spur of the moment from a line in Muddy Waters’ Mannish Boy, but instead of referring to the proverb of ‘A rolling stone gathers no moss’ as the phrase’s origin, there’s a story of slaves swallowing stones and rolling on ships. Search online and accreditation isn’t easily found, making the story sound like a mischievous piece of Wikipedia misdirection. Unsympathetic translation doesn’t help either with frequently awkward phrasing in Céka’s text pieces, and mistakes like “every pence”. Those errors just keep coming, heating being five pence for twenty minutes in pre-decimal Britain, the News of the World referred to as a magazine, Soho drawn as a ground floor residential area, Let it Bleed being titled after the Beatles album Let it Be, which was released six months later, John Mayall’s name spelt as “Mayalle”… It’s also astounding that Exile on Main Street, critically considered the Stones masterpiece, is only mentioned once, and then among nine “fun facts” at the end of the book.

Céka applies an enthusiasm to well told tales over the text, supplying enlightening quotes. Presenting these in larger font gives them a relevance maybe missed amid the plain type in the biographies from which they were sourced. Richards’ Life is entertainingly well mined.

After the quality Beatles package, The Rolling Stones in Comics is disappointing, following the formula, but lacking the care. Picking up minor errors in any book isn’t difficult, but the sheer quantity is indicative of a rushed cash-in rather than a project people invested in. They diminish what should be an attractive proposition, and the proposed audience of dedicated fans will hone in on the sloppiness far more ferociously than any reviewer.