Review by Ian Keogh

The Lone Ranger is firmly entrenched in the past. His heyday expired in the 1950s, the western genre hardly sets the world on fire in any branch of entertainment, and with his old-fashioned attitudes incorporating an aversion against killing, perhaps he’s no longer relevant in the 21st century.

Well Brett Matthews blows all that out of the water with an extremely well considered and diverting look at the Lone Ranger’s origin and early days. The opening six chapters pack a lot in, credibly revising all the essential elements of the character, while the remainder meander through assorted character-forming interludes building tension towards some righteous retribution in the final chapters.

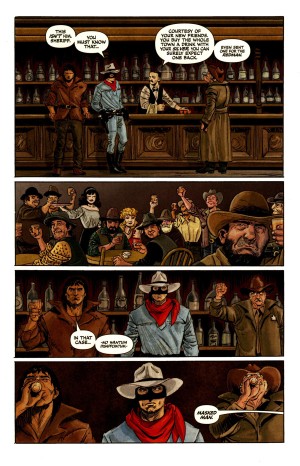

Matthews’ Lone Ranger is very much character based, with the action scenes, if not exactly sparse, certainly well spread, but this isn’t in any way detrimental. The main plot unwinds in leisurely fashion, as Matthews employs a narrative based on how matters work out in real life. There often isn’t the rapid, neat and tidy resolution found in stories, and while this might frustrate expectation, the diversions and interludes along the way are what make the series.

One element that might be considered problematical in this day and age is the previous patronising at best portrayal of Native American sidekick Tonto. Matthews sweeps all concerns aside early, establishing from the start that the Lone Ronger and Tonto are an equal partnership, and if not immediately apparent, Tonto’s reasons for sticking around withstand scrutiny.

As does the remainder of the book. Matthews uses the old west to explore current attitudes over the ethical spectrum, cleverly exploiting perceptions of the Lone Ranger to do so. This never overwhelms, Matthews always aware his primary duty is to adventure, but it’s a perpetual undercurrent often leading to surprising plot diversions.

The content of this bulky book was previously available in four volumes titled Now and Forever, Lines Not Crossed, Scorched Earth and Resolve, with more detail provided under those individual reviews, but absent from those collections is the final short. Here Matthews takes the ethical code established by the Lone Ranger’s previous writers and spreads it in captions across a simple, but effective story that’s otherwise almost dialogue free. That’s a feature of Matthews’ writing. He’s far rarer than might be assumed as a writer able to realise the visual primacy of comics, and let the artist tell the story without words when required.

That’s made far simpler when you’ve the reliability of Sergio Cariello at your disposal. He obviously relishes the genre, creating weather-beaten characters and evocative locales from the isolated farmhouse to the Ranger’s increasingly well-equipped cave. He also has some horrific incidents to illustrate, but never over-eggs them. In places his style is very reminiscent of Joe Kubert, and Cariello has a similarly instinctive storytelling facility. He doesn’t draw the entire book, though, as there’s a short and surprising interlude from Paul Pope, offering insight into Tonto’s worldview.

A possible drawback to picking up this particular volume is the high cover price. It’s a decision that defers to quality. Anyone who enjoys Westerns should really love this, and for your money you’re getting over six hundred pages of reading. If price remains a problem, check out the original paperbacks.