Review by Ian Keogh

There’s an odd leap from 1570 to 1572 to begin this volume, and those not paying attention will miss the explanation box on the indicia page filling in how events have progressed for Margot since The Age of Innocence. Certificate of chastity notwithstanding, she’s been turned down for marriage by the King of Portugal, and now awaits the arrival of the Queen of Navarre, an independent French principality in those days, to discuss an alternative marriage arrangement.

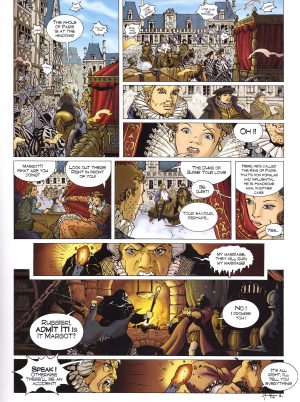

Anyone who hasn’t read The Age of Innocence will have difficulty working out who some characters are, never mind the power structure in which they all have a place. Catherine de Médici, the power behind the French throne, seems aware that the tide of Protestantism will sweep aside the established Catholic monarchies if their representatives are not brought into the establishment. To this end her life is an unceasing search for suitable marriages to sustain France’s position of power and influence, with Margot not a loved daughter, but a pawn amid these plans. However, Margot is learning the cruel ways of the European courts, and Charles IX in his position as King is less inclined to listen to his mother’s wishes.

It amounts to a turbulent brew, and as much has been supplied by Margot’s own memoirs, presumed to be historically credible, there’s a constant sense of wonder regarding what was socially acceptable, and what a monarch could get away with. Reading what they get up to and attempting to transpose such behaviour to modern day royal families causes the jaw to drop still further.

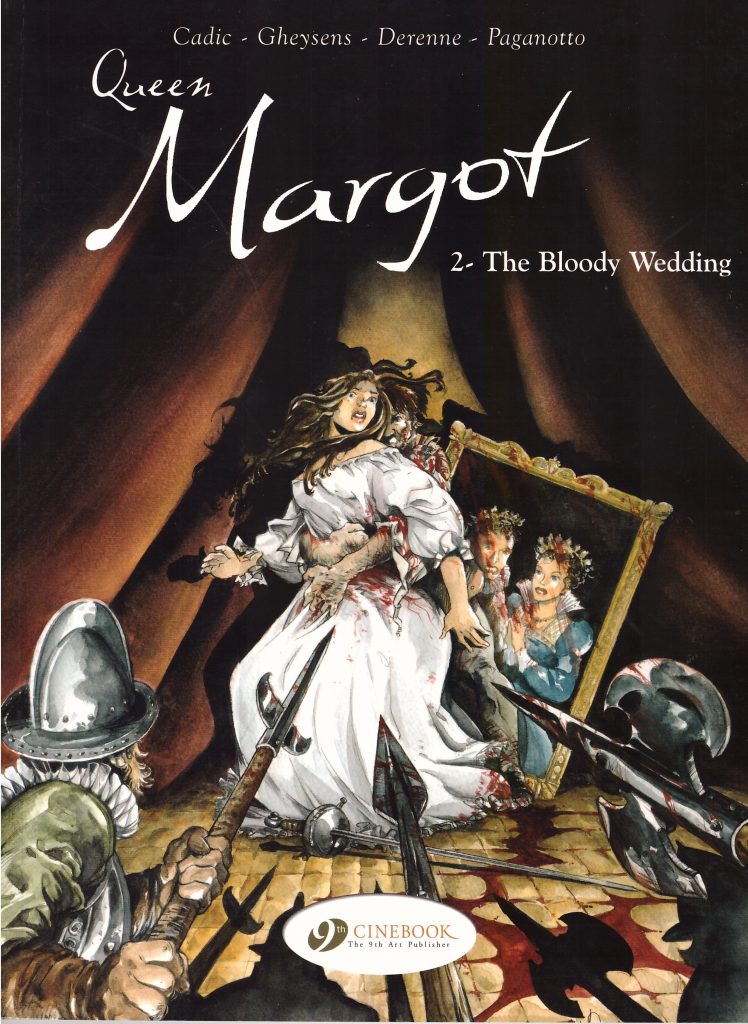

Juliette Derenne brings the historical settings to life, populating the courts and streets with people, convincing these are the most opulent locations in France, and equally astute with the massacres that Margot’s wedding unwittingly launched. As previously, although she tries to differentiate the cast via hair colour, too many of them have a similar look, and unless you pick up on details such as a necklace of sliced-off ears (oh yes!), it’s frequently difficult to know who’s endangered on any particular page. It’s not helped either by co-writers Oliver Cadic and François Gheysens alternately referring to people by their names and titles, nor by a sometimes very literal translation by Luke Spears.

Quibbles notwithstanding, The Bloody Wedding explains a horrific week of Parisian history, and one fundamental to the later accession of Henri IV, considered by historians to be one of France’s more enlightened Kings and good for the country. Margot’s recollections conclude with Endangered Love.