Review by Frank Plowright

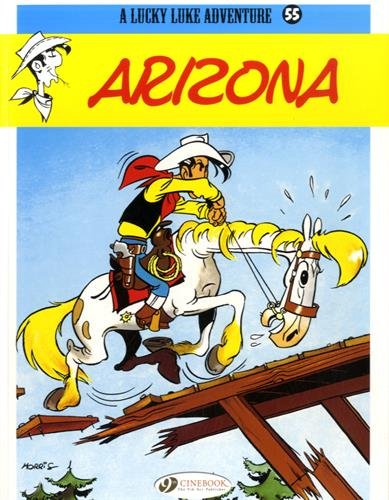

The opening twenty pages of Arizona form the starting point, the first Lucky Luke material, the equivalent of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, or Superman’s 1938 début in Action Comics. When he created what would become a life defining achievement in 1946, 23 year old Belgian artist Maurice de Bévère was producing newspaper illustrations, signing them as ‘Morris’, the pseudonym based on his name. He’d already undertaken a brief spell as an animator where he met André Franquin, another great of Franco-Belgian comics, and that career shows in the title story, one of two forming Arizona.

In his first appearance, were it not for his distinctive outfit Luke would be barely recognisable as the globally acclaimed icon he is today. Like the other European artists of his generation, Morris was in awe of the sophisticated Disney animation and there’s barely a straight line to be seen in his attempts to imbue every object with that rounded cartoon appeal. The little humour to be found is very visual, and at this early stage of Morris’ career also very laboured. He’s not yet learned to compress what needs to be seen for maximum effect, and he’s viewing a comic strip in animation terms, showing every action. In terms of style, though, it’s very good cartooning.

The almost complete lack of gags is the most amazing element when considering how later Lucky Luke strips have a high laugh to page ratio. In ‘Arizona’ only a late spurt averages out the gag occurrence to one every two pages. Were this not drawn in cartoon style the strip would almost work as a completely straight Western. It does, however, close on the familiar scene of Lucky Luke riding into the sunset although the accompanying Lonesome Cowboy song is absent.

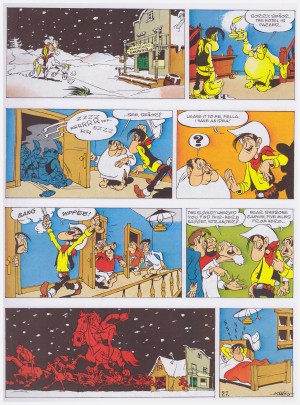

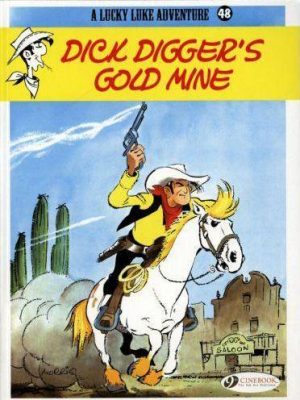

It’s followed by two single page gags (see sample page), and then jumps to ‘Lucky Luke Versus Cigarette Caesar’, originally serialised in 1949. The intervening chronological strips can be found in Rodeo and Dick Digger’s Gold Mine. This Lucky Luke is far more recognisable. He’s less rounded and has lost the lantern jaw, and Jolly Jumper is nearer his final form. By the late 1940s Lucky Luke was being serialised a page at a time, and that shows in the pacing, every page ending with a joke, but while this is still primitive Morris has picked up several storytelling tricks. He also experiments with what would become a signature detailed comic sequence within a large panel, as Cigarette Caesar tears through a Mexican pueblo, leaving chaos and stunned villagers in his wake. It’s wonderfully composed, packs in the slapstick jokes and may well have been drawn from life as Morris was living in Mexico at the time. Anyone interested in knowing more about that should look out the wonderful Gringos Locos, sadly unavailable in English.

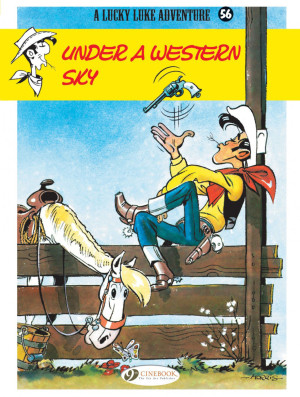

Cigarette Caesar smokes, but his odd name otherwise has no relevance. The work remains primitive by later standards, but this tale is the first indication that Lucky Luke had the potential to become something more than weekly page filler. In terms of the original chronology the material featured in Under a Western Sky follows. That original chronology is restored when the these strips feature in volume one of Lucky Luke: The Complete Collection.