Review by Frank Plowright

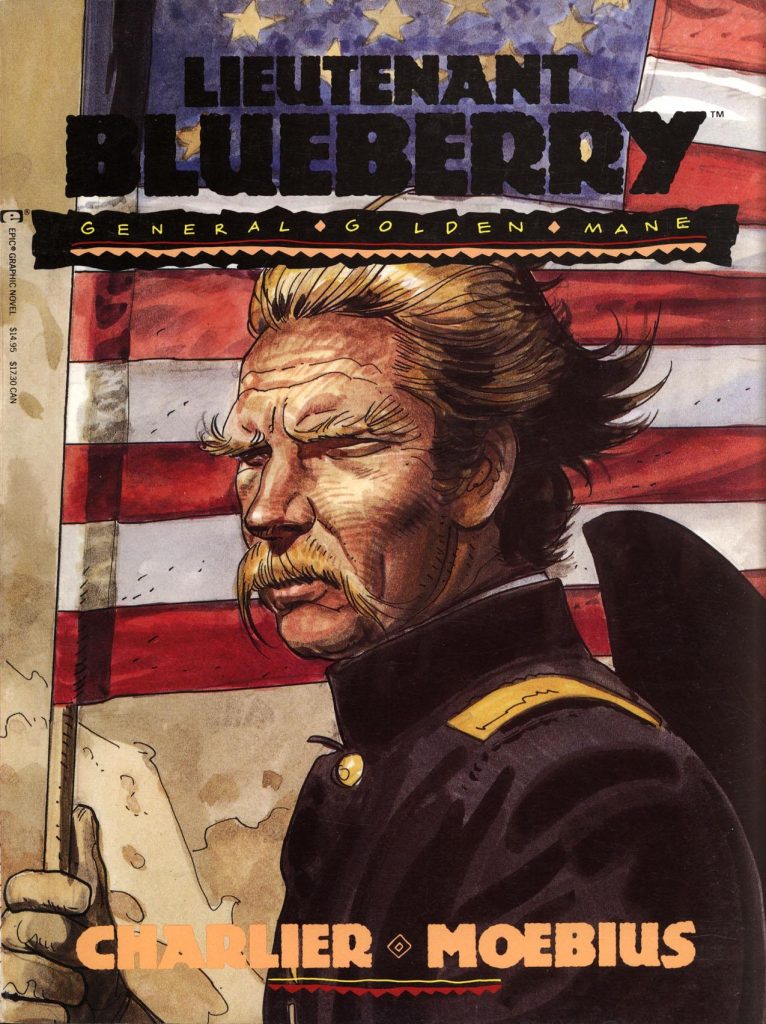

The final two books recounting Lieutenant Blueberry’s time seconded to the Union Pacific railroad are combined here in one thrilling edition. This is still the story of the stranded railroad community endangered by the Cheyenne and Sioux people over trouble that’s been fermented by others, but Jean-Michel Charlier takes an abrupt swerve. One villain’s served his purpose and is dealt with off-panel, while another different type of villain takes centre stage. The cover is a portrait of General Golden Mane, who’s General McAllister inside, but both his appearance and personality are based on General Custer.

Steelfingers concluded with Blueberry instrumental in negotiating a peace deal between Union Pacific and the native Americans. All that was needed was the seal of approval from McAllister. He, however, is the worst type of American patriot, gung-ho and bigoted, and believing in the right of the white man to occupy the land they want, irrespective of any prior claim. As the general in charge of a vast army he’s pretty much a law unto himself, and instead of rubber stamping what has been agreed he sets out with his forces to teach the Cheyenne and Sioux a lesson. McAllister is a monstrous creation, abusing power for his own ends, yet almost untouchable. Charlier, however has historical records at his disposal. In the US history books Custer has been repurposed as a man who died a heroic death, whereas in reality he died as a result of his own pig-headedness in provoking a war he didn’t need to fight. Many historians further consider tactical errors a factor.

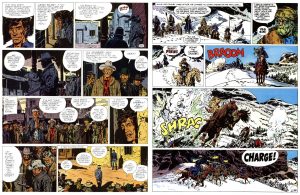

Jean Giraud’s commitment to authenticity is astonishing, especially looking back from an era when picture manipulation is endemic. His freehand art is stunningly detailed, and even serialised in Pilote at two pages per week (alongside Asterix at the Olympic Games and Lucky Luke: Dalton City) this must have been incredibly work intensive. The sample page on the left isn’t the most visually arresting, but Giraud doesn’t short change on a mob, nor on his character definition, and this section of the book has page after page of ten panels. Many of them are during the confusion of battle scenes, yet his clarity never wavers. Incredibly, he began work on The Lost Dutchman’s Mine almost immediately after completing this book.

Contrary to some reviews elsewhere, Charlier doesn’t re-run the battle of the Little Big Horn, but contrives the excitement more to his own storytelling needs, to prioritise the danger for Blueberry. Something Charlier’s very good at is the last minute rescue or intervention that’s been foreshadowed previously, and a couple of occasions here work very well. He ensures the threats Blueberry faces differ from those in the previous books, and while his plotting is more straightforward than it would become over the extended sequence beginning with Chihuahua Pearl, it’s truer to life here. In some ways that’s more satisfying. The entire Lieutenant Blueberry sequence has been a roller coaster thrill ride, and as we’d all want, the conclusion is best. The actual ending, however, is strangely abrupt.