Review by Frank Plowright

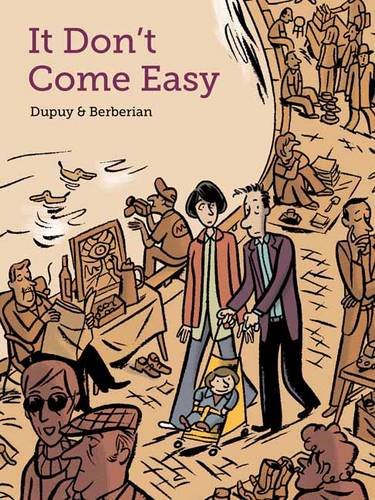

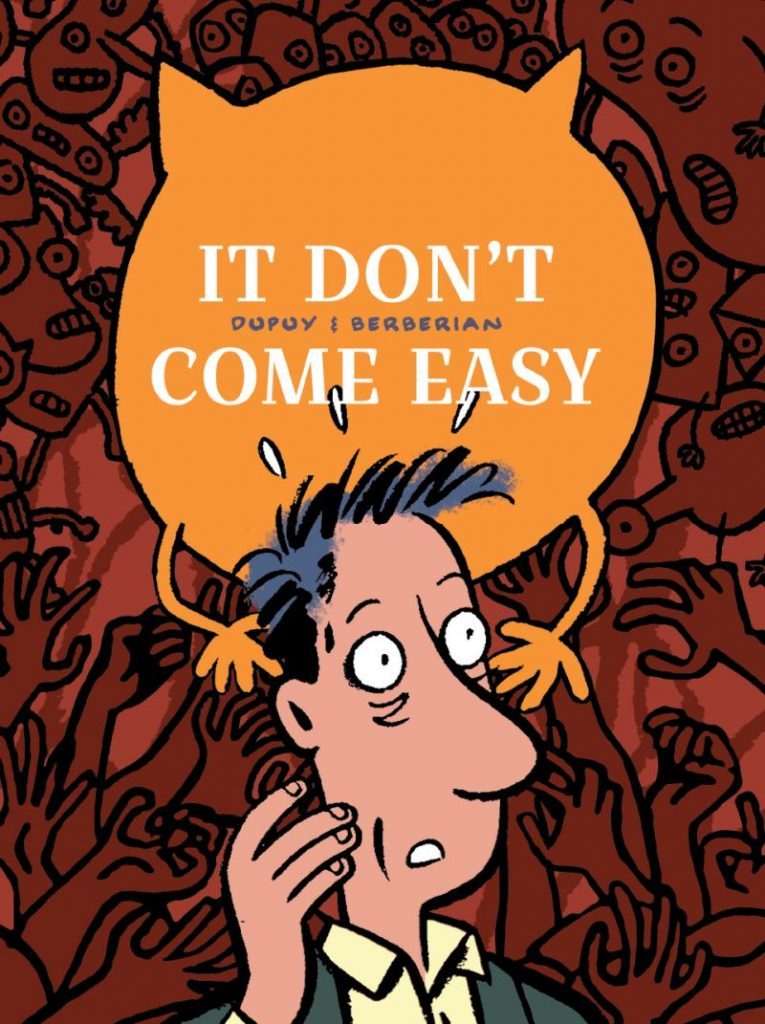

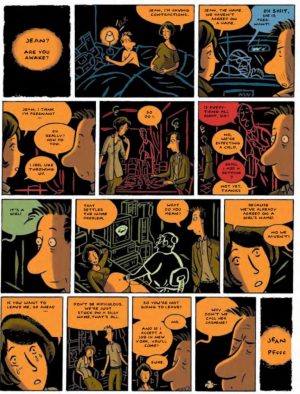

This second collection of Monsieur Jean material collects the three full length albums by Philippe Dupuy and Charles Berberian, and his final outing as his life returns to the glimpses of one or two page sequences. By the end of the stories in Get a Life, the once footloose Jean had more or less settled with Cathy, and his irresponsible friend Felix was now father to the irrepressible Eustace.

If jumping from short stories to fifty plus page albums intimidated the creators in any fashion it doesn’t show at all. They apply their sure instincts for sitcom drama, and the result is three polished stories that surprise and touch the heart. They’d been heading in that direction with some longer pieces to end Get a Life, and introduce the complexities and metaphors for which there was now room. Jean finds parallels to his life in the stories of paintings and their artists, as he hits writer’s block, while Felix becomes obsessed with recontextualising French music hall comedian Fernand Reynaud, whose stock has plummeted by the 21st century. His macabre slapstick personality guides Felix when his far more respectable, but odious brother turns up, family secrets are aired and Felix has to justify to the state that he can be a responsible father to a young boy.

These first two stories have been available in a larger format as part of the Drawn and Quarterly anthology volumes 3 and 5, and with a different translation in larger format as the Humanoids collection Monsieur Jean: From Bachelor to Father. However, the final full length story and the return to shorter gag strips receive their first English language publication here. As the longer story opens Jean has finally committed to sharing a place with Cathy, bequeathing his bachelor apartment to Felix, but he’s strangely distanced, disturbed by the box left by the apartment’s previous owner. It’s a strangely disjointed piece, featuring extended surreal dream sequences, concentration on a trio of homeless guys, and Jean plagued by the ghosts of his grandparents as a form of mystic realism. Individual sequences such as the beautifully constructed page or Felix’s admirably nutty theories about dog dirt are vintage material, and artistically it’s the same seamless blend as ever, but narratively this is the first Monsieur Jean album that seems to have the creators pulling in separate directions. The homeless guys aren’t interesting enough to justify diverting from the other cast members, and too many threads eventually lack a satisfying pay-off.

A reversion to single and two page gag strips for the final Monsieur Jean album isn’t entirely successful either. They’re beautifully drawn and have a connecting narrative, but it’s also clear that having taken him from single and carefree to married with child Dupuy and Berberian have little left to say about their title character. He’s the focus of a few domestic jokes, but far more space is allocated to Felix’s disintegrating life and the woes of Cathy’s single friend Agnes, those being introspective despair, not too far removed from Claire Bretecher’s spiky social observation in Frustration during the 1970s and 1980s. Felix is on repeat cycle, leaving the funniest character in this selection his provocative adopted son Eustace, revelling in unexpected freedom.

The opening two stories are five star material, and compared with most slice of life comedies the following two albums are better than most, just not Dupuy and Berberian firing on all cylinders.