Review by Ian Keogh

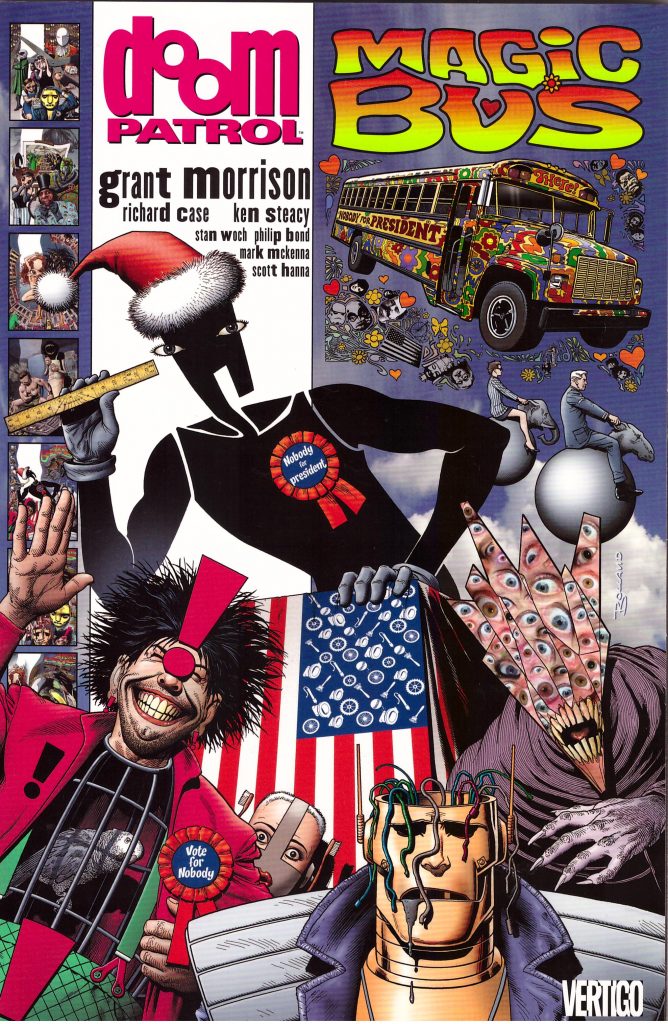

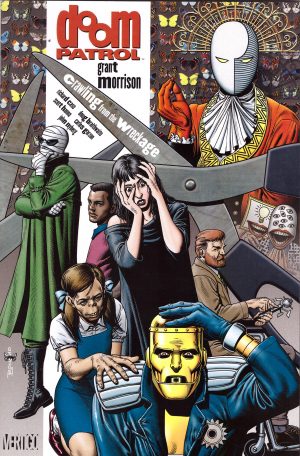

More than any other Grant Morrison Doom Patrol collection Magic Bus showcases a variety of storytelling approaches, beginning with slapstick satire and ending with a look into the manipulative mind of Niles Caulder and his terrifying agenda. In between there’s a loving 1960s Marvel homage, a mind-bending trip into the unknown and multi-layered horror, before the true revelation of how the Doom Patrol came to be.

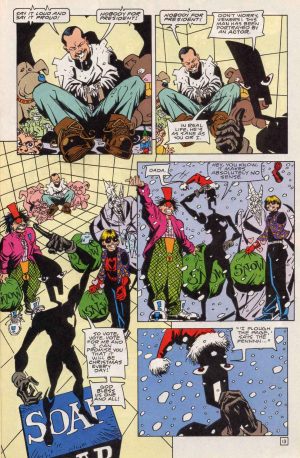

Amid all the admiration for the surreal and conceptual qualities, Morrison doesn’t receive enough credit for how funny some of his Doom Patrol stories are. The title story concerns Mr Nobody and his Brotherhood of Dada spreading their hallucinogenic gospel amid a presidential campaign, having acquired the means in Musclebound. Planting truth among the nonsense, the targets are easy, but well aimed, and Philip Bond’s looser art is a welcome change.

While primarily a Marvel homage, the following story works on several levels. It’s a pastiche of the overly dramatic writing styles, while also being Ken Steacey’s loving tribute to the dynamism of Jack Kirby’s art, and Morrison’s love letter to a 1960s Kirby Fantastic Four story in which the Thing is drugged and replaced. Strip away all the meta-levels, and the primary plot would work today as the basis for a Marvel movie.

Morrison’s been building the transformation of Rebis for some time, and the result is ammunition for anyone who sees him as a pretentious, one trick pony. He’s not, but this is experimental and obscure for obscurity’s sake, self-indulgent with no concessions to an audience. What may or may not be metaphors for rebirth and transformation abound, and those able to pick through and interpret coherently are surely few. Richard Case is back for the art here, and draws the remainder of the book in his traditional superhero style, now sometimes inking his pencils, and Stan Woch a more sympathetic inker than Mark McKenna has been previously.

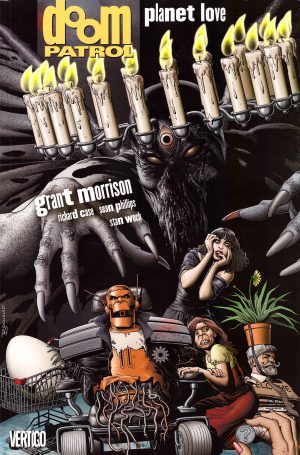

The next two chapters begin the disintegration of the Doom Patrol, concluded stunningly. This is more a horror story, establishing definitively who the core of the Doom Patrol is. Only Cliff wants to keep them together. Over the past couple of volumes, apart from ill-considered exploitation, Crazy Jane has fallen by the wayside, her multitude of personalities and powers unsuited to the plots, but here Morrison delves back into her fractured mind to make sense of who she is. Anyone offended by the use of rape as a device in comics look away now. Is it trivialising? Surely no-one can have seen Crazy Jane as a role model before now. The entire concept of the Doom Patrol is that they’re fractured, the methods something Morrison explores in the final chapter, so a central question if they’re to be seen as convincing characters is why they’re fractured, and what would cause such disintegration. In Crazy Jane’s case it’s entirely feasible that abuse and rape would. That story isn’t finished here, a matter for Planet Love, but after the final chapter it’s difficult to see how any of the Doom Patrol will be around for that.

Alternatively this content can be found combined with Planet Love as Doom Patrol Book Three, or with all Morrison’s other Doom Patrol work as The Doom Patrol Omnibus.