Review by Ian Keogh

Doom Patrol had been originated as a marginalised, weird feature. Strip it down, and the 1960s incarnation was about three people given a second chance at life, but not as they knew it. Robotman’s polished metal approximation of humanity housed a human brain. Former actress Rita Farr grew to giant size, and Negative Man had to remain swaddled in bandages, occasionally able to soar for sixty seconds as a creature of radioactive impulses. Their saviour, the Chief, Niles Caulder, was an acerbic Victor Frankenstein in a wheelchair. They fought strange creatures, and their original run ended with the entire cast being killed as they sacrificed themselves to save a town.

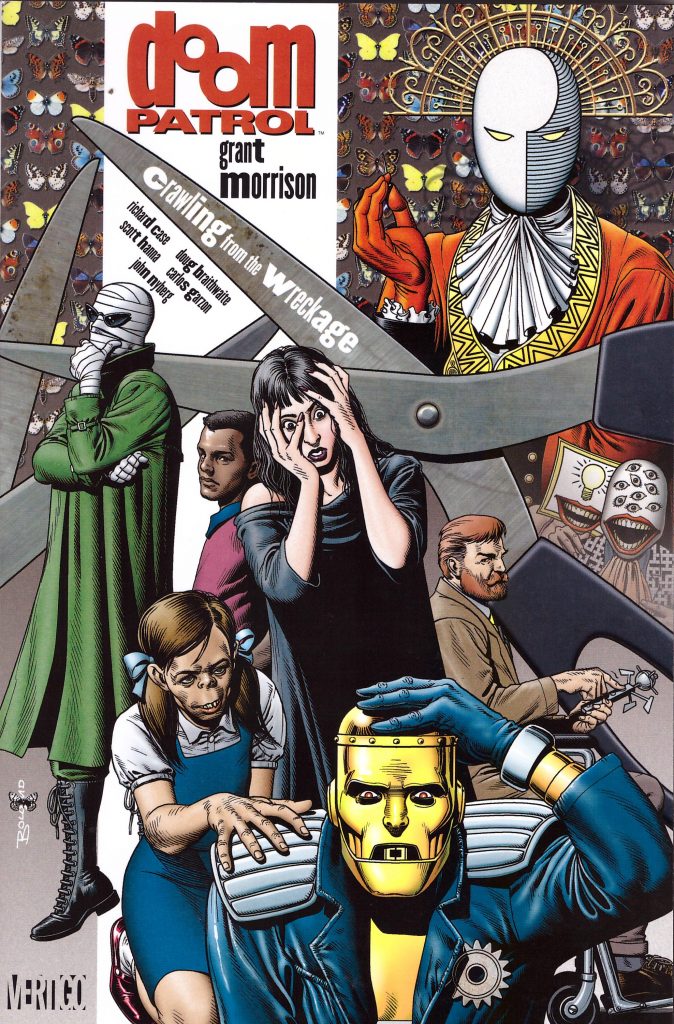

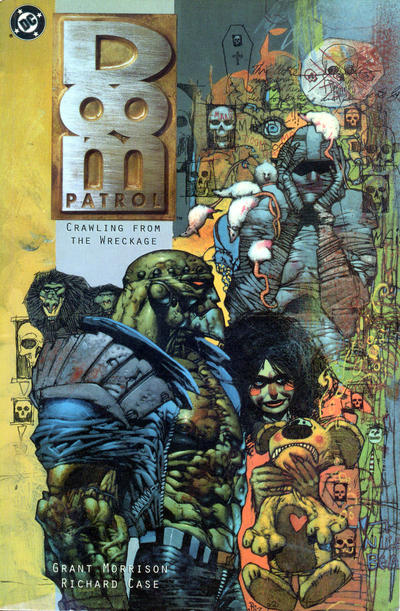

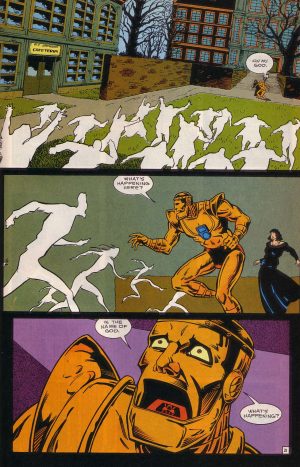

Although in his afterword he claims his younger self avoided the Doom Patrol, the inherent strangeness of that original version appealed to the adult Grant Morrison in 1992 when handed some of the characters revived as more standard superheroes. Undistinguished work from his predecessors had taken the revival to the verge of cancellation, so is the title of Crawling From the Wreckage a comment as Morrison was given a free hand? He prioritises ideas. All but the opening chapter here feature some form of superhero battle, but not with mundane super villains. Instead over two stories they fight creatures of nightmare like the Scissormen who literally cut people out of existence while speaking cryptic crossword clues, and Red Jack, who considers himself God and is also Jack the Ripper. Cities intrude from other dimensions, while people are excised from ours, leaving just empty outlines.

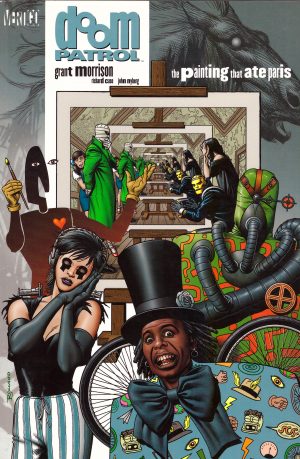

Morrison upgraded the personalities. His Chief is even more grumpy, sinister and manipulative, Cliff Steele (never Robotman for Morrison) is depressed about his situation, Negative Man is now Rebis, incorporating a woman as well as Larry Trainor, and most of the previous 1990s cast is discarded in favour of new characters. It’s Crazy Jane who’ll become Morrison’s signature, a fractured woman with 64 personalities, each with a distinct super power, reflecting his own approach to Doom Patrol. He’ll throw in philosophy, sociology, Fortean events, jokes, strangeness for strangeness’ sake, and there are rudimentary thoughts about gender fluidity. His narrative captions form a torrent of creative thought, cast out randomly.

A more imaginative artist than Richard Case would have taken Morrison’s scripts and turned them into nightmares. Instead Case drags everything down to standard superheroics, and while that might not be ideal it’s surely among the factors enabling such a long run. Instead of the waning audience being confronted with the entirely avant garde from new kids on the block, at least what they were getting looked comfortingly ordinary. Doug Braithwaite in his first DC work draws the final chapter, and that’s also ordinary, but he’d progress and improve, whereas there’s almost no difference between Case here and his work five volumes later.

It might be expected that Doom Patrol has dated. Other more out there pre-21st century Morrison projects have, but this isn’t a series someone else could successfully imitate and dilute, nor is it Morrison deliberately pushing the boat too far. It took his mind to create the gestalt and this opening jolt is still fresh and original. If only the art looked better. Here’s an idea. Why not produce a re-mix with another artist reinterpreting the scripts. The weirdness continues in The Painting That Ate Paris, or alternatively they’re combined as Book One or there’s The Doom Patrol Omnibus, a hardcover collecting all Morrison’s work on the series.