Review by Karl Verhoven

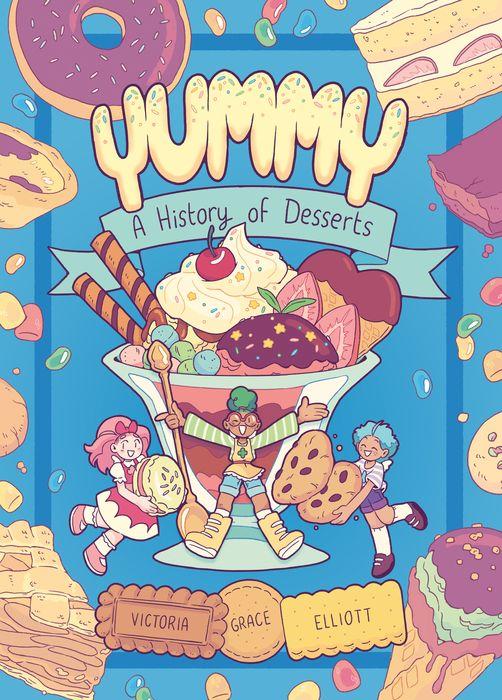

Anyone with a sweet tooth isn’t going to think twice about heading for this seductive confection, designed to look like the colourful, sugary constructions it explains. It meets the expectations promised by the cover, yet readers whose tastes are more savoury may require greater persuasion. With that, Victoria Grace Elliott scores early, explaining how Ancient Persia engineered a method of preserving ice all year round.

That’s noted in the opening chapter dealing with ice cream throughout history, which sets the recipe for the remainder of the book. Peri, the overall host, introduces other representatives of mythical realms to explain the sweet specialities of their area, prominent chefs are “interviewed”, there’s an explanation of how each treat is made, and legends about innovations where the first use isn’t clearly known. Each chapter closes with a recipe, and these are easily understood and diligently provided, explaining the reason for minor processes that might seem pointless, and how they improve the final product. Subsequent chapters deal with cakes, brownies, donuts, pie, gummies (jellies and sweets), cookies and macaroons (here called macarons), and many other desserts are hauled in besides, with Elliott applying the same enthusiastic attention to detail and global outlook.

Sociologically, there’s a similar pattern to each dessert, most devised as specialities for royalty and the very wealthy, as the ingredients were often sourced from distant lands, and so something very few could afford. Only from the 1800s did the concept of desserts filter down below the wealth line. What’s apparent in every chapter is that the common form of a dessert in the West isn’t necessarily the preferred version elsewhere, and how cross-cultural experimentation with ingredients shaped what we enjoy today. Among this Elliott drops in a considerable number of surprising facts. The very concept of a dessert, for instance, is relatively recent, as for centuries sweet and savoury dishes were served alongside each other, and the sheer amount of time once needed to beat cake ingredients for the best results is a jaw-dropper. Even today with all the advances of technology the maxim of “without fresh ingredients you don’t get a fresh cake” still holds some truth, although the applicable equation measures time against taste.

The drawing is kept simple and practical, with the emphasis on bright colour and decorative patterns for backgrounds to set off the illustrations of the desserts, which all have the intended appeal. Some omissions are inevitable, the British Christmas pudding being one, but it’s a casualty of priorities. Even allocated 230 pages, this can’t be an exhaustive compilation. However, Elliott densely, cheerily and informatively fills the pages, and along the way you’ll learn why donuts have holes, the difference between pie crusts and that the nursery rhyme line about blackbirds in a pie wasn’t as far fetched as it sounds. And you’ll surely be tempted to have a go at least one of the recipes.