Review by Frank Plowright

The slogans applied to social and employment reorganisation in 20th century Communist states evoke a nationalistic ideal, and some live on, yet the shocking practicalities of them remain largely unknown to the ordinary person outside the country concerned. Mao ZeDong’s Cultural Revolution, for instance, here examined by Emei Burell in terms of how it affected her mother. The Cultural Revolution lasted from 1966 to Mao’s 1976 death and one aspect was shipping sixteen million students from their city homes to work in the countryside. The cities had a shortage of jobs while China’s rural resources were under-exploited. This was no short term relocation either. While students could return home for visits occasionally, and exemptions could be granted for parental need, many spent ten years of their lives hundreds of miles away from their family homes.

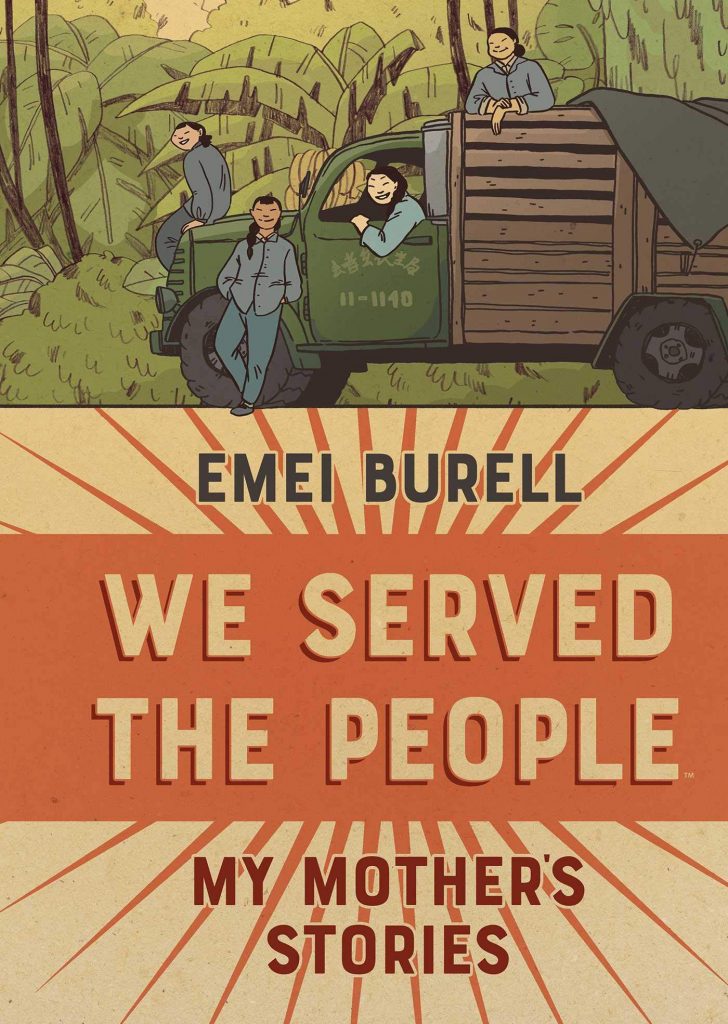

Growing up in the UK, Burell would hear her mother Yuan’s stories about life in a remote plantation, and these form the basis of We Served the People. Yuan’s explanation over several pages provides the background and ideology before Burell starts her mother’s recollections. There’s a good reason for the opening chapter’s tale of a particularly dedicated worker, but compared with other memories the notion of a lorry being stuck on a narrow road lacks drama. As the surprise at the end is well kept, this chapter would have been better placed at the end of the book, or as served up as an epilogue. Its ordinary nature dampens enthusiasm for what’s to come instead of raising it.

The remaining stories are of greater interest, not least for emphasising the hollow nature of the Cultural Revolution. The reality was millions of students not completing their education, removed from their families, allocated farm work and after a long day made to attend “lessons” consisting of nothing more than reading pronouncements from newspapers or the further propaganda of Mao’s writings. Yuan proves more determined and adaptable than most, coping with corrupt officials, and learning new skills providing opportunities for advancement, if not a return home. To an audience used to the freedom of choosing a career, like Burell herself, the job allocation system alone seems appalling, and Yuan provides several examples of people being held back. When she’s allowed to take a university course via TV broadcasts, she recalls the only available room for students being so packed she needed to stand in the doorway.

Burell’s art is compact and expressive, using a muted palette. Once or twice her limitation in capturing a portrait makes it difficult to distinguish between people, but otherwise there’s an appealing delicacy to her linework and the restricted colours serve as a metaphorical echo of her mother’s limited choices. Photos accompanying the art would have been better captioned to provide more context, or at least to identify Yuan among others she’s pictured with.

Yuan’s oral history opens the door into a world few readers will know about, and captivates in doing so, also supplying a distressing glimpse into human nature. If exploitation of others is possible, there are people who’ll indulge. However, we know from the start that Yuan survives her rural experience, and that’s a comfort throughout.