Review by Frank Plowright

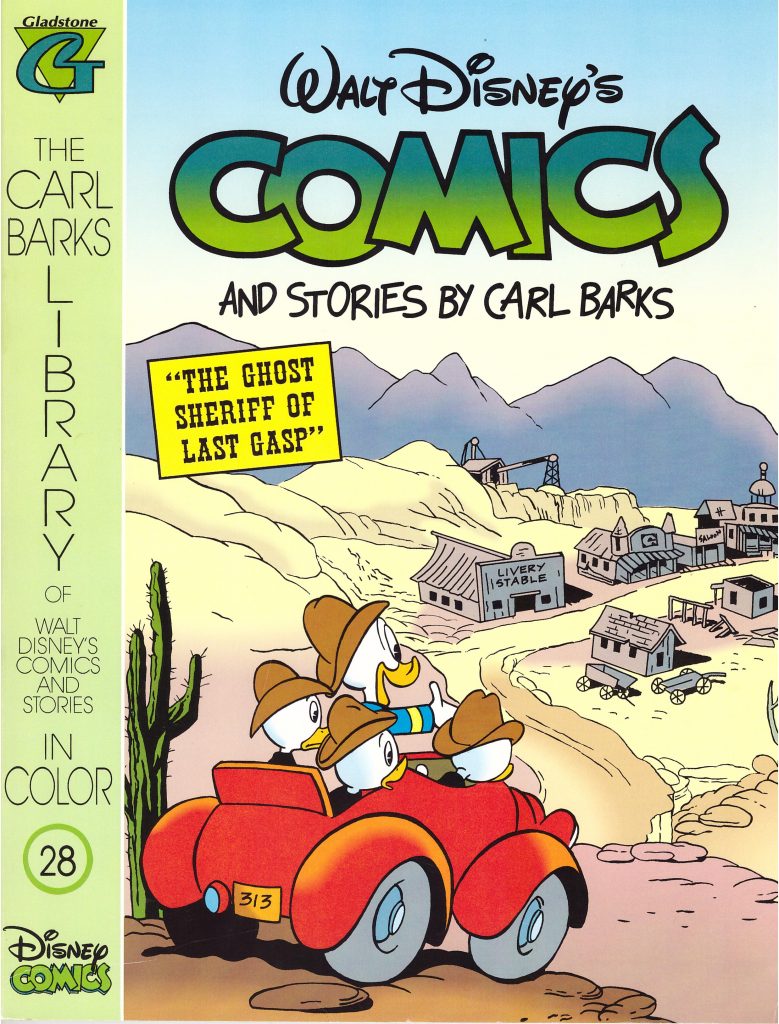

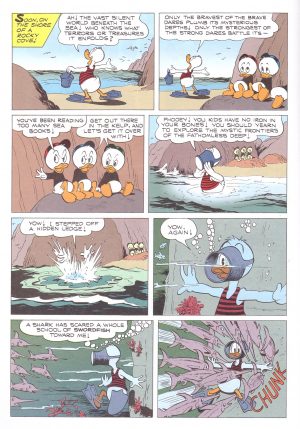

In the spring and summer of 1955 Carl Barks treated his readers to five stories each completely different in mood and emotional pull. There’s the mad chase of Donald Duck desperately trying to retrieve a lost item, a ghost mystery that turns into surreal comedy and ends with a beautiful silhouette, Donald’s deep sea adventure, Donald driven to distraction by noise, and the inevitable contest with the supernaturally lucky Gladstone. Each of them is perfectly plotted and drawn, each of them funny and surprising, and each of them with a broad streak of absurdity as Barks let his imagination run wild. That everything fits together so neatly gives the impression of effortless creation, but of course, the truth is anything but, and Geoffrey Blum’s accompanying essay analyses that opening story via the discovery of sequences excised by Barks as too predictable. It shows almost an entire page of work, pencilled, inked and lettered, that Barks discarded on the basis of it not meeting his standards. On deadline and with only ten pages to produce that’s an incredible discard rate. Barks is right, and his revised pages are funnier, but the original gags aren’t poor, and no-one else would have complained.

A characteristic of almost all the stories is how they begin with one idea and evolve into another. The exception is Donald’s aversion to noise, cited by Barks as a favourite among the ten pagers he created. Because he can no longer stand the noise in his street, Donald moves with his nephews to the quietest neighbourhood in town, and the joke becomes Donald’s intolerance and temper escalating a ridiculous situation into something apocalyptic. The preparation for the eventual pay-off is slipped in early and Donald brings about his own downfall. It’s very satisfying.

In the mid-1950s Barks was on a golden streak with his mastery of the ten page format, and that continues in volume 29.