Review by Frank Plowright

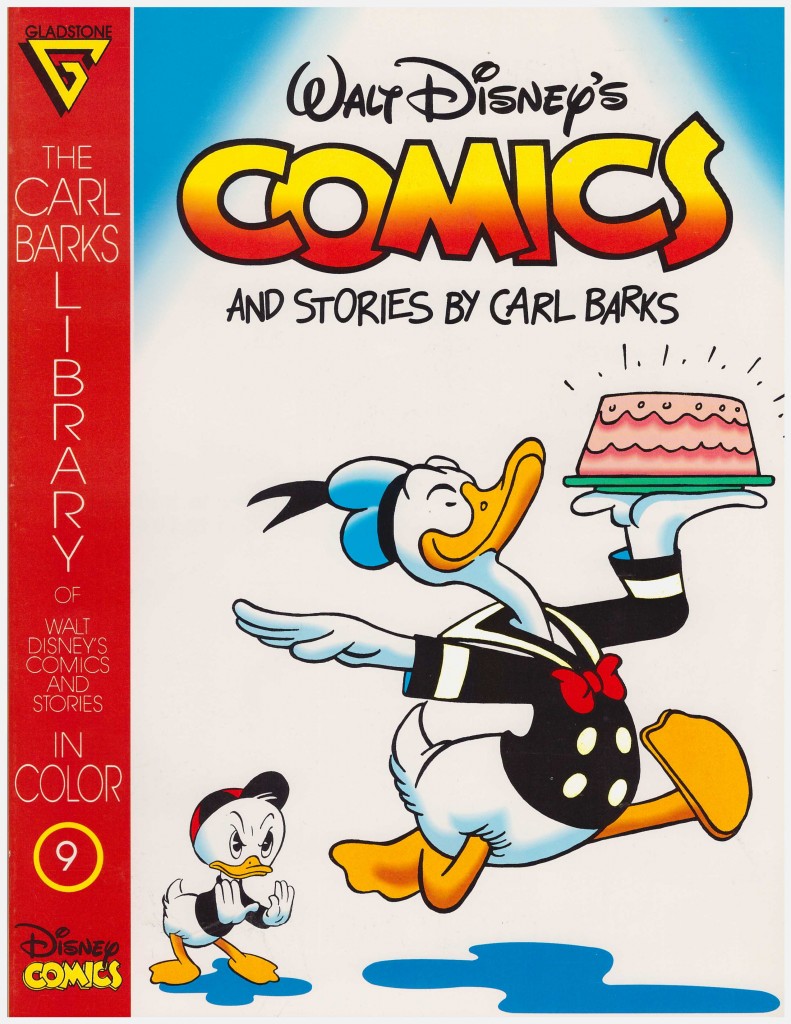

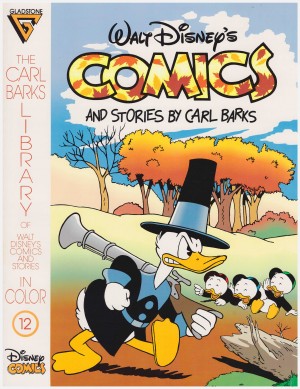

The cover displays a fantastically smug Donald Duck en route to present the cake he’s baked for Daisy. The glowering Huey underneath suggests that what cometh after pride is about to occur. As with all the covers to this series, it’s an enlarged image from an interior story, in this case actually a composite. Producing the covers in this manner has the added benefit of highlighting art that may otherwise be passed by in the course of a story, where it’s only a single panel. Everything about Carl Barks’ illustration is perfect, from the closed eyes to the walking on air in the belief he’s about to rectify an earlier bawling out.

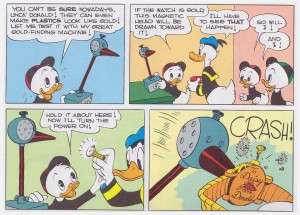

The illustration is lifted from a tale in which Huey invents a gold-detecting machine that’s a little too enthusiastic, and unfortunately some earlier deceit on Donald’s part is revealed. After inspiration running thin in the previous volume, Barks is back to form in late 1946 with clever twists and inventive plots, while the art never went off the boil.

It’s the opening and closing stories that are the best. The opener has Huey, Dewey and Louie persistently bunking off school, with Donald always one step ahead. It’s an interesting story for not exactly complying with the strict ethical code Barks’ applied. The kids do get their come-uppance for wrongdoing, but also revenge on Donald. The final tale is Barks’ first ten pager to see publication in 1947, and features the misadventures that occur when Donald takes pity on a howling stray cat that’s the scourge of the neighbourhood.

Featuring animals in stories about humanised ducks is always a leap of reader credulity, and there’s another concerning Thanksgiving turkeys. Barks supplies some magnificent bad-tempered brutes. Donald at one of his many plot-convenient short-term jobs supplies the final story, with him employed as a bill collector this time. It’s the weakest of the bunch, despite Barks’ supplying a whimsical selection of creditors, and a neat twist as the kids try to earn some money.