Review by Woodrow Phoenix

The legendary animation pioneer and showman Walt Disney has arrived at a crisis point in his life and career. Obsessively overworking, micromanaging his team to the point of collapse and finally losing all control of his faculties, trashing everything, he passes out in his office. His wife Lilian peels him off the floor and transports him to a specialist facility that treats artists in mental and spiritual exhaustion: the Von Spatz Rehabilitation Center in Santa Monica, California.

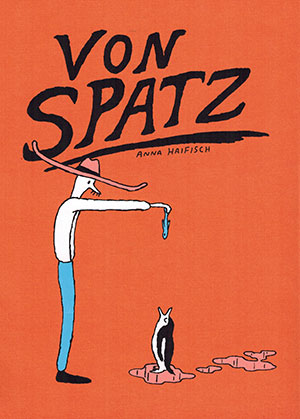

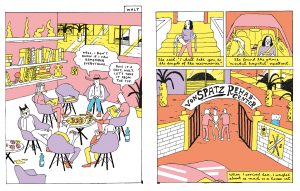

Anna Haifisch uses her noodly line and her hallucinogenic colour palette of orange, pink, yellow and blue to concoct a thematic examination in Von Spatz of the intense emotional and mental pressures that creativity places on artists, through the person of Disney and two other commercially successful and famous men, Tomi Ungerer and Saul Steinberg, who are also recovering from their own breakdowns. This nurturing environment has an atemporal mixture of resources including Bertold Lubetkin’s penguin pool from London Zoo (fully stocked with penguins to walk up and down the spiral ramp), a hot dog stand, a very well-equipped art supply store, a copy shop with the latest duplexing photocopiers, studio facilities, and an art gallery to display the results from all the rehabilitation that will reshape these three during their art therapy sessions and restore them to full function.

This book has a lot in common with The Artist in its absurdist mashing-up of many disparate elements to create a kind of super pure distillation of creative angst, down to its most basic components. It demonstrates how the same situations recur endlessly with only the faces changing as each artist undergoes the same journeys and arrives at the same places, wherever they may have started out. There are lots of sly references to pop cultural situations, figures and fine art totems littered throughout, but the situations are so impersonal in their generic moods that it’s almost arbitrary as to who the protagonists are. The three who are the focus of this story could have been any three creators chosen at random for all the use Haifisch makes of their own personal histories, but in a way that is the point. Or one of them, anyway. Von Spatz works the themes Haifisch works with in her other books into a longer, more sustained pitch here as she contrasts the indulgent, luxurious externalities of the art world with the existentially crippling questions that never quite go away no matter how much success you have: “How arrogant it is that I demand attention for my tentative scrawls when there is so much misery in the world?” asks Disney as he leaves the rehabilitation center behind.