Review by Frank Plowright

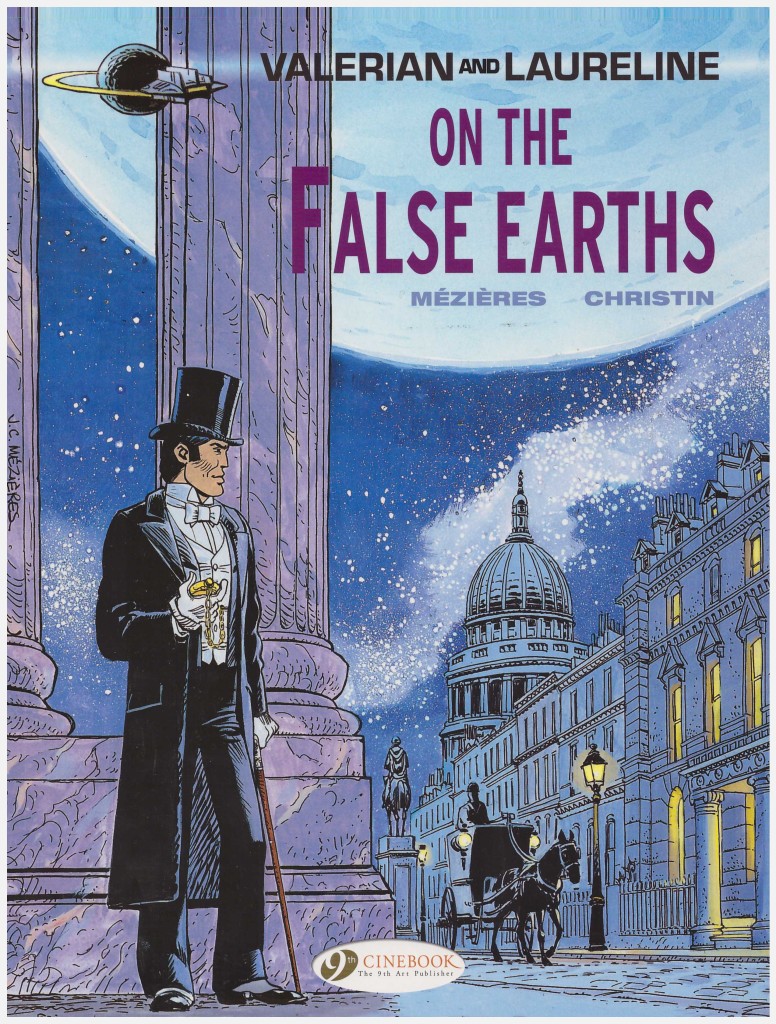

This is probably not the book with which to start the adventures of Valerian and Laureline, but it’s a cracking story packed with ideas well beyond most science fiction comics dating from the early 1970s.

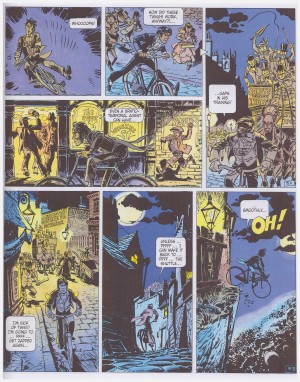

It opens with six pages of Valerian seemingly involved in the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Jean-Claude Mézières effortlessly recreating the period setting. It’s a deliberately puzzling location for a science fiction series, but ties into a tradition of historical drama being a far more popular genre in European comics than elsewhere. Valerian seemingly dies before appearing in late Victorian England and having another micro-adventure. This is spliced with a scene of Laureline monitoring Valerian’s experiences via the visual display of a control panel, accompanied by another woman, seemingly senior, patronising and unpleasant.

We shift through a few more slightly off register historical scenarios in which Valerian appears, until around halfway through writer Pierre Christin hits us with a fine revelation.

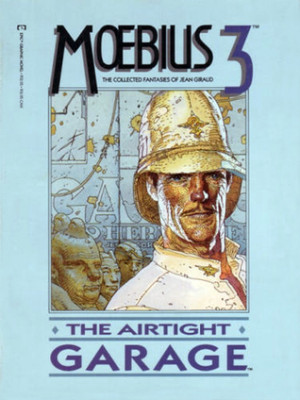

This is a book requiring some context. It was the first Valerian and Laureline story to be created after the début of groundbreaking French science fiction anthology Metal Hurlant in December 1974. That was founded by a group of young comic creators frustrated at the limitations of the entrenched Franco-Belgian comic scene, and fired the imaginations of many.

The creative spark about Valerian and Laureline had been an influence on the breakaway creators, and Christin was now inspired to step into new territory with some hard science fiction concepts and a philosophical debate around them. The specifics would enter spoiler territory, but they make for the best in the series to date.

Mézières is in playful mood throughout, delivering a cameo for fellow adventurers Blake and Mortimer, and saving a nice touch for the final panel. He reproduces Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party in his own style, reducing that to the background while placing Valerian and Laureline at the forefront.

In terms of character, this album is the first in which Laureline admits her feelings for Valerian are more than platonic admiration for a colleague, and there’s an interesting take on self-awareness, perhaps not too far removed from Blade Runner. The film was still a few years in the future on publication, but Christin was surely aware of Philip K. Dick’s work. This isn’t to say he’s copying. His extrapolation of a similar theme is in passing, and has entirely different consequences.

Heroes of the Equinox is the next in the series and both are available in the third hardcover Valerian and Laureline: The Complete Collection.