Review by Frank Plowright

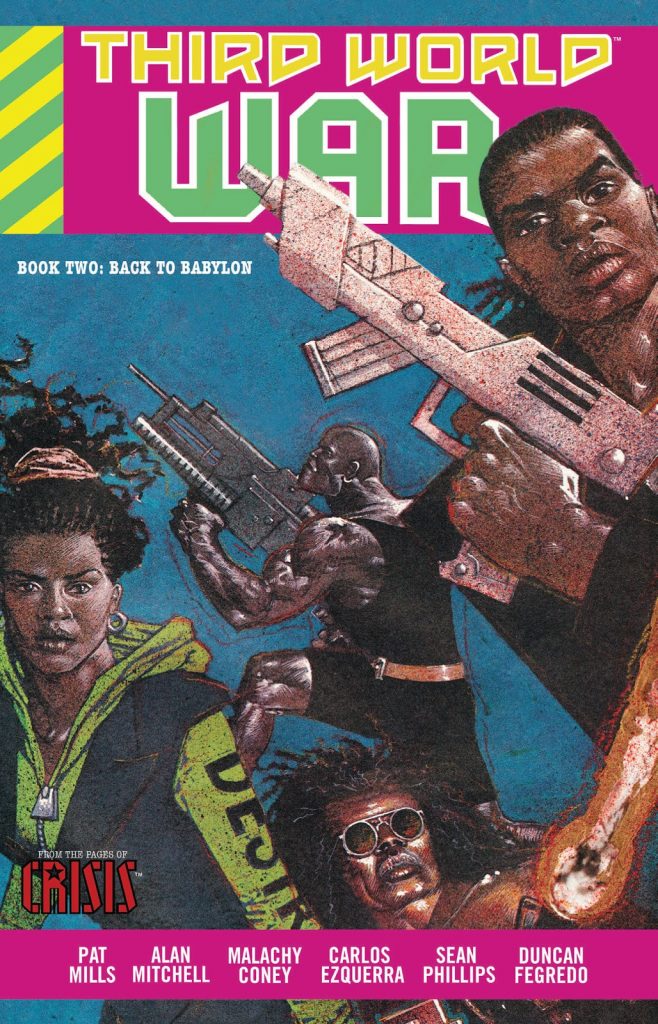

Third World War’s first volume saw Pat Mills extrapolate the then present day imperialistic iniquities of the late 1980s into a near future, corporate-sponsored war in Central America. Back to Babylon broadens the horizons of what constitutes war as Pat Mills makes less pretence about dealing with a future. He continues the theme of how multinational corporations prioritise their profits above any human consideration, and broadens his remit to cover animal rights activists, the contemporary situation in Northern Ireland and radicalism among London’s Black population among other matters.

Throughout his career Mills has always been proactive about working with promising new artists, and while Carlos Ezquerra draws more than anyone else (sample left), Back to Babylon features extended sequences from Sean Phillips (sample right), with several other young artists used. The results are mixed, with John Hicklenton not yet having found his disturbing style, so just awkward, but Duncan Fegredo already very good and Phillips improving page by page. Mills also works with co-writers to convey the feeling of their area, so Black writer Alan Mitchell contributes to a plot about the Black African Defence Squad, and Belfast resident Malachy Coney co-writes sections dealing with Northern Ireland.

However good the intentions are, the stories are as mixed as the art, with Mills orchestrating a multi-agenda polemic that rarely settles long enough in one place to do it justice. However, Third World War has to be seen in the context of its era. British comics had never seen anything remotely as angry and informed about the inequalities of society. Mills researched deeply and wasn’t just preaching to the choir, he was grasping a mass market opportunity, and passing on an alternative view to that supplied by newspapers and TV news. In the pre-internet era learning about police brutality, political trickery and what life was like in Belfast under the British army was worth the price of the occasional contrived conversation such as the one about Eve’s upbringing. Mills packs a lot in, but by today’s standards it’s not subtle, although there are moments of bleak nuance such as a nice line about sugar following a glimpse into Jamaica’s past.

It’s interesting to see that some words have been redacted, words now considered unacceptable even when used by obvious racists in the story context, but other equally offensive terms with similar intent survive.

Distressingly, the names may have changed, but the same corruption, prejudice and repression has resurfaced in the 21st century, even more blatant than it was in the 1980s as it’s now carried out with greater means of scrutiny. Mills still has something to tell us, and potential readers still have a lot to learn.