Review by Ian Keogh

In a different world Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelance invented the computer in the 19th century. In ours Babbage’s theoretical Analytical Engine, conceived by him, but with much subsequent input from Lovelace, never developed beyond the planning and diagram stage. As Sydney Padua relates, Babbage ranted to anyone who’d listen about the administrative short-sightedness of not funding his machine, but then the authorities operated on the once bitten, twice shy system. They’d invested £17,000 in his predecessor, the Difference Engine, often wrongly identified as the first computer (in theory), when it was in fact more a calculator. At the time £17,000 could have funded the construction of two battleships. This is learned via the wealth of footnotes and endnotes supplied by Padua, who’s as interested in what was going on around the title characters as she is in them, gleefully satirising the Victorian greats, highlighting hypocrisy and pomposity and passing on a wealth of intriguing information.

Broadly speaking, Padua opens the door to an alternate world where Babbage and Lovelace’s Analytical Engine was actually created, and many of his other suggested devices became commonplace. Although little known now, Babbage was a celebrity of his era, and as the daughter of Lord Byron attention was also focussed on Lovelace from an early age. They were both considerably eccentric geniuses, Lovelace, for instance, losing a fortune by today’s standards convinced she could find a formula applicable to betting on horse racing. Babbage was professor of mathematics at Cambridge, but was a polymath interested in many subjects connected or not. One of his most celebrated works deals with economics.

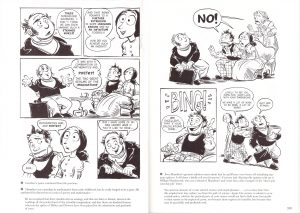

Because there are so many required explanations, Padua’s own intelligence and sardonic commentary is as delightful as the world she weaves around the title characters, and indeed her efficient cartooning. Purists might carp that the comics wouldn’t work without the explanatory footnotes as per the sample spread, given an extra layer by them, but why pick at something that’s so much fun? Yes, Babbage would have done, but there’s no need to sink to his level of pedantry. Take a warning, those not of a mathematical bent may struggle with some aspects despite Padua’s brave attempts to simplify complexity, but don’t be put off. There are so many delights beyond the mathematics in this dense pleasure.

While weaving the miraculous, there are places where Padua is carried away, and a chapter featuring novelist George Eliot investigating whether the Analytical Engine can order a novel isn’t as compelling. There may also be frustration at Padua not explaining how Babbage and Lovelace’s machines were supposed to work. Be careful what you wish for! This is explained in great detail in an appendix, and reading makes it obvious why Padua hasn’t clogged her story with it. The machines were designed by two imposing mathematicians and engineers, and require considerable explanation. Even in simplified form they’re difficult to comprehend, and if back in the day scientific genius Michael Faraday couldn’t grasp it, there’s no shame in admitting you can’t either.

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage lives up to the title for anyone with a curious mind. It’s packed with fascinating snippets of Victorian life, celebrities and social conventions, all deeply researched, and Padua’s own personality shining through seals an inspirational graphic novel.