Review by Ian Keogh

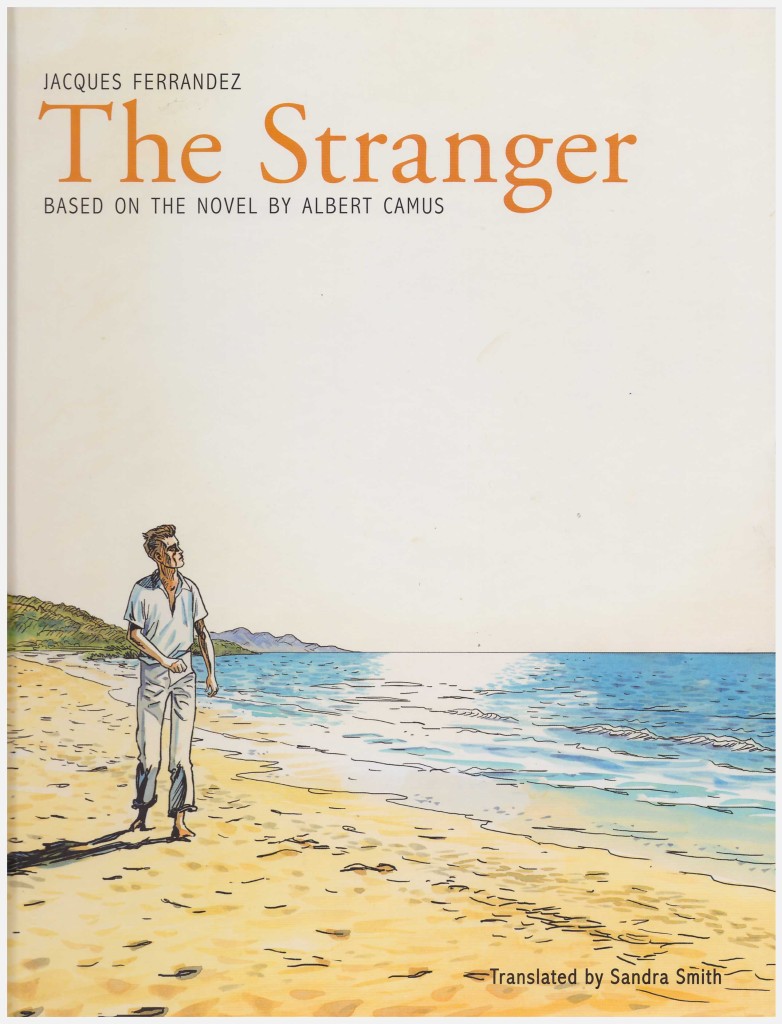

Albert Camus’classic novel of alienation and disassociation appears most commonly in English as The Stranger, but is more accurately translated as The Outsider.

Like Camus himself until the late 1930s, Meursault, only ever referred to by his surname, has lived his entire life in French occupied Algeria. Little is revealed about his past, but he appears to be in his early twenties, and as the story opens he learns that his mother has died in the nursing home where he placed her, unable to pay for care at home. Meursault is emotionally distant. He cares enough about Marie Cardona, with whom he becomes reacquainted early in the novel, to want to sleep with her, but when asked about marriage he’s ambivalent. He’s asked for his views by others on several occasions, and each time claims not to care one way or the other, a person unable to lie even at the cost of causing pain to others. This is contrasted by Raymond Sintés, who has an apartment in the same block, and is a man in whom violent emotions fester and erupt, the pain he administers physical.

As the story proceeds it’s uncertain if Meursault is telling the truth, or merely adopting a pose, but when Raymond’s problems escalate Meursault takes decisive action that shapes the remainder of the book. His honesty concerning his detached attitude to others paints him as a monster.

Camus invested himself within Meursault. Contrary to the prevailing orthodoxy of the times, Camus viewed marriage as a hindrance rather than a blessing, a view noted in the story, and had plenty to say about organised religion. Meursault’s one descent into intense emotion occurs when discussing belief in God.

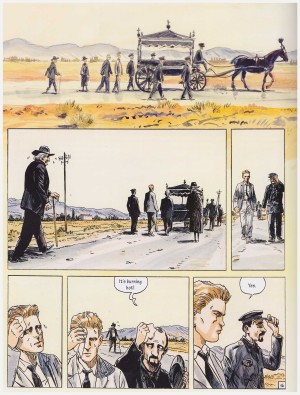

Algerian artist Jacques Ferrandez produces a faithful adaptation, the latest step in a career in which his interpretations of French colonialism in Algeria have been prominent. Despite the era just providing background detail for The Stranger, Ferrandez has applied a great deal of thought to the adaptation. A repeated visual technique is to distance with large illustrations devoid of black ink setting a scene. It’s surprisingly effective, and these are surrounded by smaller panels supplying the finer detail of the dialogue. He provides an appropriately enigmatic Meursault, the analytical emotional void at the centre, but when it comes to the reactions of others he often lapses into melodrama. While these exaggerations are never entirely comedic, neither are they far removed, and there’s an irony concerning a key early sequence featuring French comedian of the era Fernandel. Part of his routine involves repeating the same sentence in several different ways to induce contrasting emotions. Ferrandez doesn’t convey this well.

The enigmatic strength of the plot, however, retains a beguiling compulsion long after the times that produced it have have passed. As with the novel, Ferrandez leaves us wanting to understand what cannot be understood or explained, and the notion that we all fear individuality.