Review by Ian Keogh

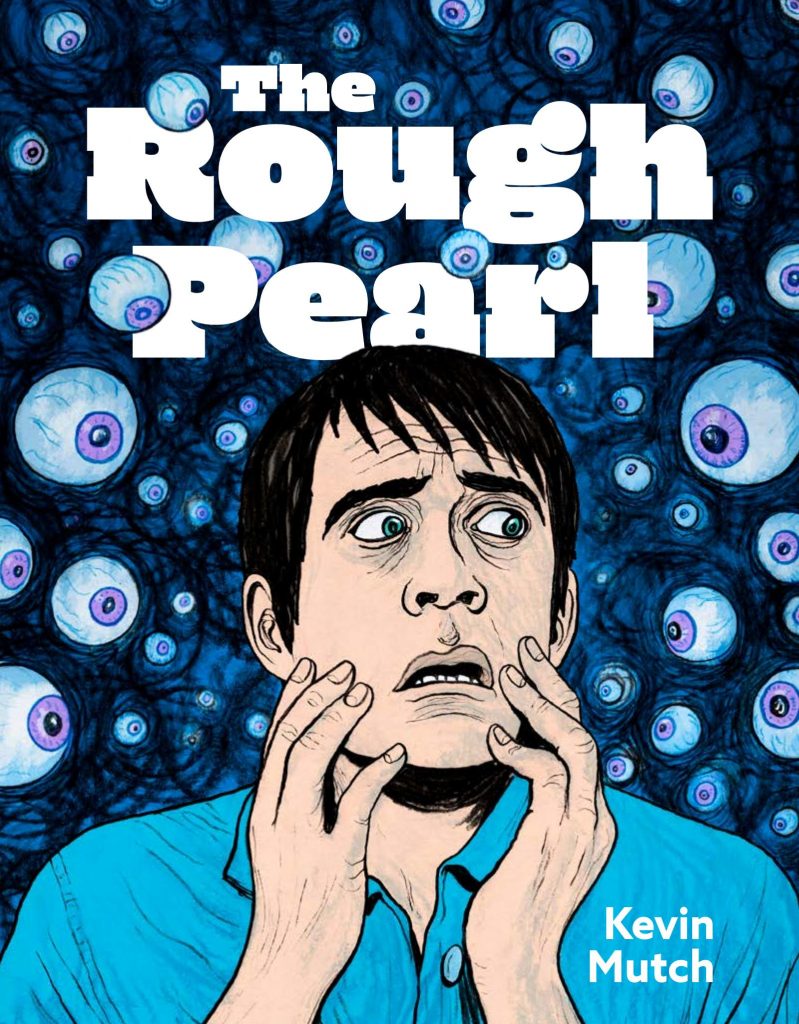

Anyone who’s spent any time lecturing at a university or college will instantly bond with Kevin Mutch’s put upon Adam Kline, employed part time in 1995 to teach computer manipulation at an art institute. Mutch instantly supplies the reality by dumping on Kline over the opening pages every indignity he’s ever suffered while teaching. The dim students multiply, Kline has regular demands to attend meetings outwith working hours, deadlines are moved up requiring overnight attention, and that’s before he has to go home for a tense dinner with his wife’s working colleagues who’ll decide her possible tenure. It’s seat-squirmingly hilarious Abigail’s Party territory with the terminology of the pretentious wanker additionally thrown in. That’s only the half of Adam’s problems, though. He’s started having hallucinations again despite his medication, and there’s the inevitable attraction to a student.

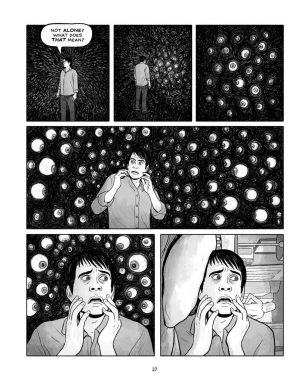

It’s easy to laugh at the sad sack Kline has become when his own artistic aspirations butted up against reality, but a deeper delve considers the depressing value wider society places on art, which is a theme returned to throughout. His art manipulates reality, also manipulated to sell art. And can it be possible Kline’s life is being manipulated? Mutch cultivates an unreality via the blackouts Kline experiences. Some are accompanied by weird dreams, others end with him waking up in the middle of some completely normal activity, the missing hours a mystery. It’s successfully unsettling, with staring eyes a recurring motif, whether as a pair or multiples, while Kline is simultaneously warned he’s always under observation.

If only briefly, most adults have experienced the feeling of not being in control of their own lives, and Mutch returns to this in various forms as Kline stumbles through the train wreck his life is becoming. There’s an almost sadistic pleasure taken in piling yet another trauma on Kline’s accumulation, all drawn in a traditionally accomplished figurative style well away from any art discussed. Yet the metaphors abound, Kline as self-absorbed as anyone he sneers at and despises, failing to take in the messages from what may be his own subconscious about how he’s complicit in his own failings.

Despite a refined sense of personal injustice, Kline’s passivity and predatory buttons have faulty settings, one continually applied when the other would be more suitable. That being the case, and given The Rough Pearl’s airing of internalised voices, perhaps any expectation of a neat ending was always wishful thinking, and it could be argued providing it would betray the reality presented. Yet being true to one ideal concludes a thoughtful and original graphic novel in an open-ended and tired way. The journey is accomplished, but needed something more transparent.