Review by Frank Plowright

The Smurfs are one of the few European cartoon series to have caught on in a big way in the English speaking world. Unlike Asterix or Tintin, however, this has been via their adventures being animated and movies rather than the original graphic novels of which The Purple Smurfs is the first.

Oddly, considering their later success, the Smurfs made their début in the medieval comedy adventures of Johan and Peewit, only two of whose albums have ever been translated into English. This indignity has been compounded by the second now recalibrated as The Smurfs and the Magic Flute, the second in the 21st century Papercutz series. As both features are the creations of Peyo (Pierre Culliford) and the Smurfs proved far more popular, he probably wasn’t too bothered. It took just three appearances in Johan and Peewit before the Smurfs were promoted into their own series, and from that point Johan and Peewit’s albums became sporadic.

For those who’ve managed to avoid the ubiquity of the Smurfs, they’re little blue humanoid creatures with small tails who live in forest communities. Brainy Smurf wears spectacles, but the likes of Jokey Smurf, Greedy Smurf and Lazy Smurf are virtually indistinguishable beyond their names, apart from community leader Papa Smurf, who’s bearded and wears a red cap and trousers in preference to white. Later albums also feature the single Smurfette. Their attraction is viewed on every page with Peyo’s charming cartooning bringing a world of small creatures to life.

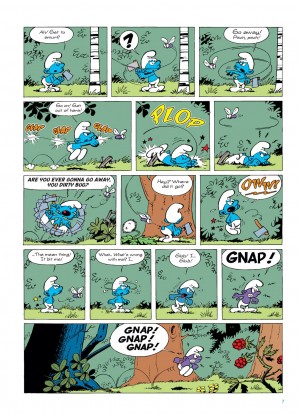

The early Smurfs solo stories were tryouts when first serialised, so this album houses three strips. In the title story a single smurf is bitten by a purple fly. It turns him purple, applies an aggressive attitude and the single word vocabulary of “Gnap”. Every other Smurf he or one of his converts bites is also transformed. Papa Smurf remembers the condition, but he was just a youngster of 108 when it last occurred, and he can’t recall the cure, and as more Smurfs are transformed, that becomes the problem. Yvan Delporte’s plot for the second story is better. A smurf wants to fly and the creators construct an escalating series of slapstick gags about his attempts to achieve this. Better still is the final story about a Smurf who wants some peace and quiet. Peyo’s pastoral scenes and the building of a fairy tale hideaway in a tree stump are story elements to fascinate any imaginative child, and despite adversity there’s a happy ending to all tales.

Kids will find the graphic novels every bit as entertaining as the Smurfs in other media. Adults, however, may find the joke of replacing all verbs in their speech with the word ‘smurf’ wears thin very quickly, although no less than Umberto Eco once wrote an essay on the semiotics of the Smurf language. It apparently originated when Peyo and André Franquin were in a restaurant, Peyo wanted the salt, momentarily forgot the word and instead asked for the schtroumpf, which is how the Smurfs are known in Europe. This is apart from the Netherlands from where their English name was taken.

European readers seeing this volume may be surprised that the converted Smurfs are purple, as in the original volumes they remain black. An editorial explains what could be seen as a ridiculous degree of cultural sensitivity, or, alternatively a sensible attitude to avoid offending anyone if that’s possible. This is also available in a larger format as part of the first Smurfs Anthology.