Review by Ian Keogh

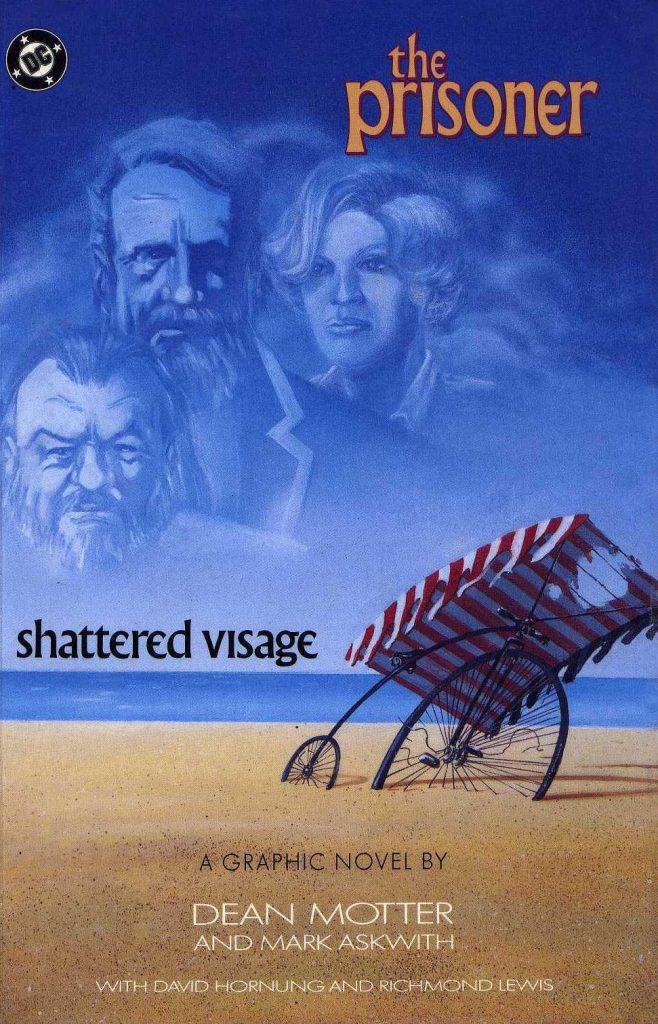

In the days before video tapes or DVDs, British TV series The Prisoner was the very definition of cult TV, screened in the 1960s, then not again until 1984, introducing its mysteries and allegories to a second generation. Seventeen enigmatic episodes aired about a man abducted to live in a strange, distinctively designed place only ever referred to as the Village, tested, questioned and not permitted to leave until he’d satisfactorily answered why he resigned from his previous position as a secret agent. He resolutely refused to co-operate no matter the intimidation or manipulation applied. The purpose remained undefined, and the man only ever referred to as Number Six was left stranded, his true story never revealed. Until Shattered Visage.

Dean Motter and Mark Askwith co-plotted what takes place twenty years later. No-one knows for sure where Number Six is, although it’s believed he remained in the Village when it was liberated by UN troops. A current agent only ever referred to as Thomas has recently released a book based on the memoirs of a Village interrogator, always referred to as Number Two. The truth was laboriously censored, but after access to the original material Thomas has concerns about the past and what the Village is, yet his investigations are frustrated by his MI5 bosses at every turn.

Motter’s art takes different forms. Sometimes everything is hand drawn, other time it’s worked around photographs, yet dates from an age long before widespread digital manipulation. It’s stylish, although the attention to the fashion of the times makes some characters look dated, whereas the TV show’s design was intended as timeless. Elsewhere Motter carefully includes pleasing visual nods to episodes from the TV series, amid well cultivated decay, and likenesses of actors McGoohan and Leo McKern were on the agenda, but if not seen full face on they’re not always convincing.

A very leisurely progression characterises Shattered Visage. Motter very rarely uses more than four panels to a page, and these are often used to set a scene or a mood. Both creators display a respect for the original series in the way their plot progresses. Although it features plenty of references to keep Prisoner fans happy and uses the Village backdrop, this is a new story using the same themes of control. The TV show ending, a hallucinogenic miasma, is recontextualised, in order to set the plot going, and what is revealed and created fits logically with established lore, while taking some satirical sideswipes at the British establishment. The dialogue has a precision inviting interpretation during scenes involving secret service officials, and clever wordplay characterises the scenes featuring the original Number Six, the twisting of meaning now ingrained in him, but he remains an enigma. As he should.

Ultimately the creators supply some answers without destroying the series’ mystique, so don’t look for everything to be neatly tied up, which wouldn’t be attuned to the original material. However, this is stretched well beyond the plot supplied, and some aspects introduced that might be expected to have answers don’t. This especially affects an escape at the end. Anyone immersed in the world of The Prisoner should enjoy revisiting it, but pick this up cold without that knowledge and much will seem inexplicable and dated.

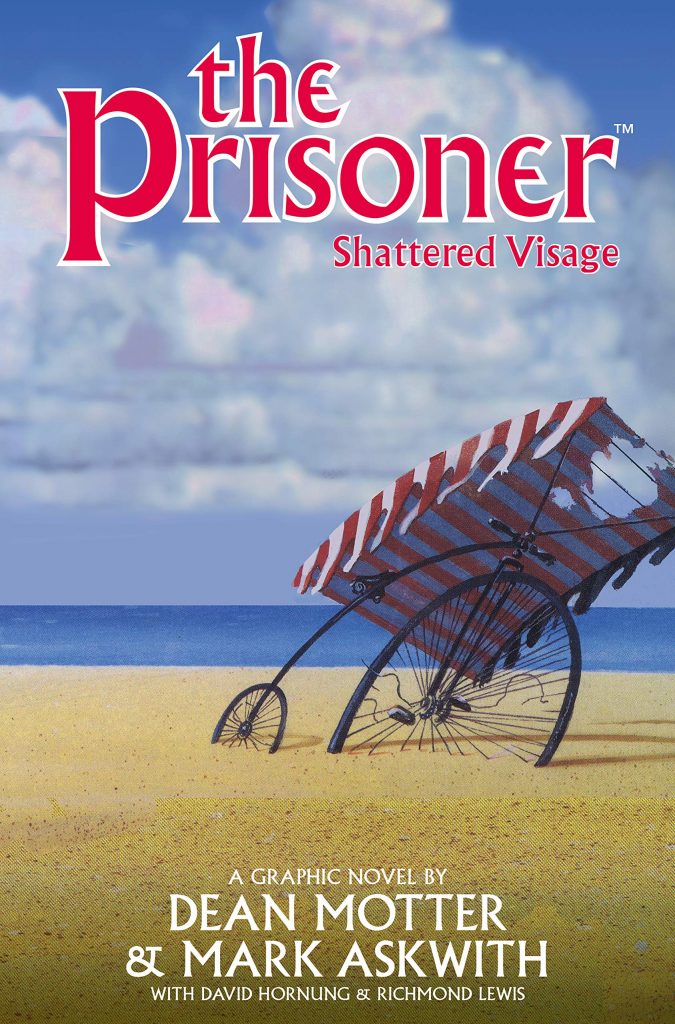

Titan Comics’s 2019 reissue features some productions sketches and aftethoughts from Motter, along with a few pages of his pencilled art before being inked.