Review by Frank Plowright

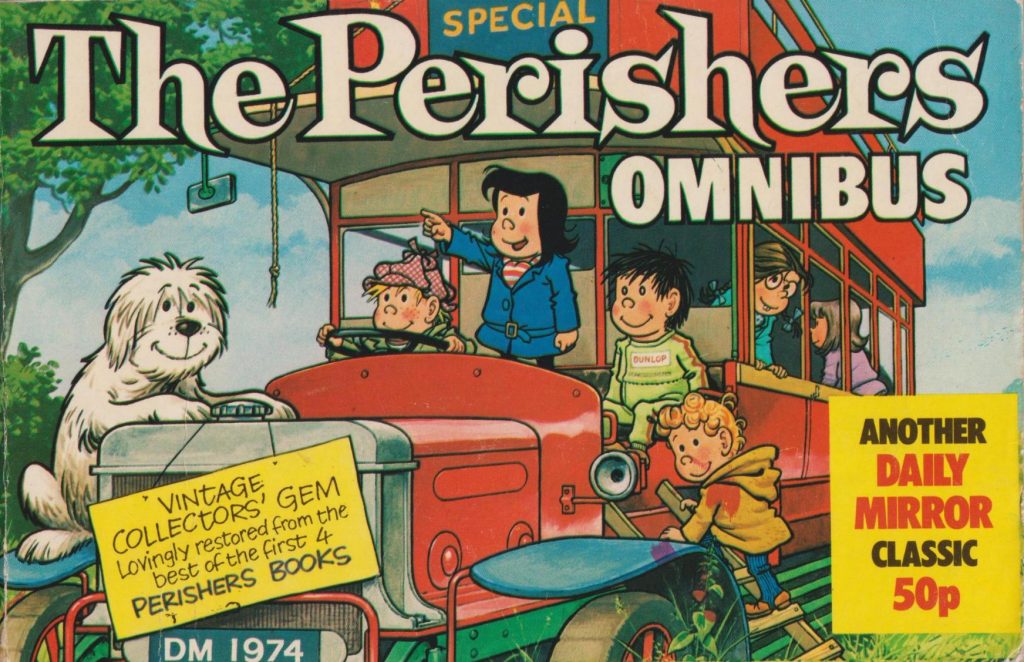

The Perishers exemplifies the difference in respect for newspaper strips in the UK and the USA. It’s a British national treasure that ran for almost fifty years, generated an animated TV show and provided a daily dose of eccentric characters, sophisticated wordplay, impeccable comedy pacing and exquisitely paced slapstick, all beautifully drawn. In the USA such a beloved cast would generate lavishly produced hardcover volumes reprinting the series chronologically from 1959 to 2006. In the UK the only archiving beyond annual collections was three selections of early strips issued in 1974, 1975 and 1976 as The Perishers Omnibus. This earliest of those is now fifty years old. It’s a shoddy fate for Maurice Dodd’s witty scripts and the masterful cartooning of Dennis Collins.

The title is a now outdated expression, in the 1950s applied to groups of unruly children, and while evocative, it’s not entirely appropriate as the cast are hardly hooligans. Maisie is an aggressive force of nature, completely unable to understand boys’ activities, yet very willing to disrupt them, and able to hear a coin drop into sand from a mile away. Marlon’s not the sharpest knife in the drawer, yet considerate, and the younger Baby Grumpling is actually the most mischievous, although often from a sense of curiosity than outright malevolence. He understands what’s said, yet pretends he can’t, and it’s only toward the end of this selection that he talks. However, it’s the genial Wellington and his sheepdog Boot providing the heart. Dodd never explains why Wellington is homeless, at first seen living in a section of construction pipe, which generates his philosophical pessimism. Boot is often mystified by human behaviour, and the venue through which several long-running supporting characters are introduced. Few of that rich supporting cast appeared early, the most prominent here being the pairing of Fred the socialist beetle and a caterpillar who stunted his growth by smoking. The rockpool crabs feature in annual Eyeballs in the Sky sequences, while rich kid Fiscal Yere and Maisie’s friend Plain Jane would only ever make occasional appearances.

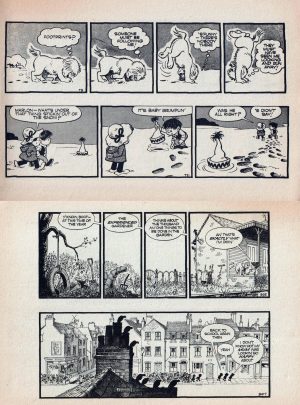

In his late thirties when The Perishers started in cruder form in regional papers, by these nationally circulated strips, Collins is an accomplished cartoonist supplying an expressive cast within tightly produced backgrounds. He’s good with movement, likes a silhouette, and even at this formative stage experiments with layout. An early strip is a continuous progression of thought balloons over a single panel until they reach Baby Grumpling. A signature technique is the single background split into different panels as seen on the sample art, accompanied by an almost Lowryesque strip, included here, but from later in the run than the remaining content.

In providing a world without adults Peanuts is an obvious starting influence, but The Perishers is something separate, decidedly British and infused with humanity, Dodd impressing as good natured as his scripts are never mean spirited. He repurposes poetry, redefines the stethoscope as an implement for scoping up steth and most importantly provides a solid joke every time.

While continuity was never a great feature of The Perishers, there were nevertheless sequences where daily strips built on their predecessors, so while this is a selection, it’s pleasingly presented in chronological order. That isn’t the case in the collections originally gathering these strips, The Perishers, The Perishers Strike Again, The Perishers Back Britain and Playtime With the Perishers.

If you can find it, treat yourself to a volume of British newspaper strip history every bit the equal of lavishly praised American strips. This selection is magnificent, yet The Perishers would improve.