Review by Frank Plowright

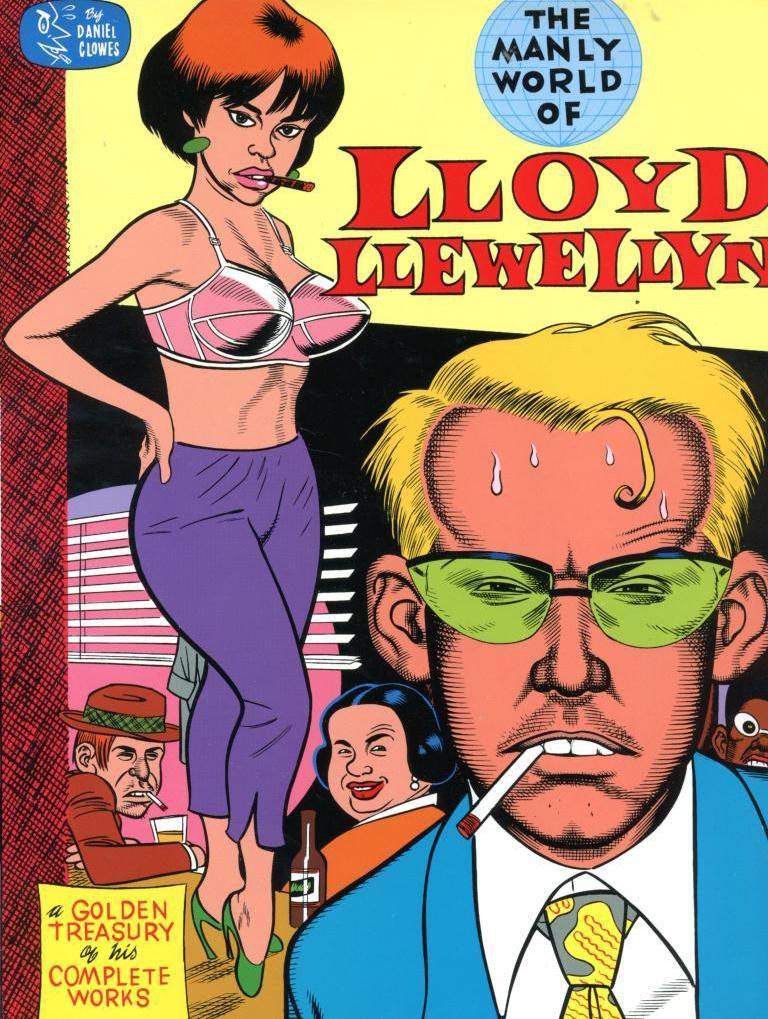

The world Daniel Clowes created for his first comic series was Lloyd Llewellyn’s offbeat and kitsch strangeness, set in the early 1960s. To give some perspective, when Clowes began publishing these stories the Hernandez Brothers only had fifteen issues of Love & Rockets under their belts, while Peter Bagge was only three issues into his Neat Stuff series. Clowes was therefore an early adherent of a largely Fantagraphics initiated movement gradually wedging their way into the awareness of people who wanted something more than Spider-Man from their comics.

#$@& provides a more selective sampling of Lloyd’s adventures, but this is the better collection for being complete, which has several advantages. The most obvious is seeing the progression of Clowes from the already talented artist of the earliest material to one adopting a thicker inking line and discarding the greytones of the first stories. Clowes drops us into a fully formed world from the start, featuring gangsters, voluptuous women from Mars and a clunky, retro-designed robot. These elements are gradually refined to prioritising mood, noir narration replacing most of the whimsy and wilder inclusions, and it’s this latter material providing all content for #$@&. Again, the variety makes this the stronger collection.

Those later stories are nearer the distanced and reflective narratives with which Clowes would make his name, and this subsequent work wouldn’t need Lloyd’s one-note personality as a magnet for the strange and uncanny, nor the sometimes forced humour. It would work more atmospherically and effectively creeping around the edges of his tales than having crazy hot-rod drop-outs from beyond Jupiter in our faces.

That said, at their best the Lloyd Llewellyn stories are a smart fusion of early 1960s chic with all the trappings and an extremely individual mind filtering the late night TV watched ten years before the stories were created. The deliberate trashiness and sleaze contrasts the always dapper Lloyd, and the occasional drop into something deeper is enjoyable. A satirical view of hollow beatnik philosophies is funny, as is the greatest horror of them all, Lloyd witnessing what he’d become later in the 1960s, in the 1970s and in the 1980s.

A clever collection title indicates this as very different from the career defining Clowes, effectively separating it, and while the art is a complete giveaway, Lloyd Llewellyn could otherwise almost be the work of a different creator.