Review by Ian Keogh

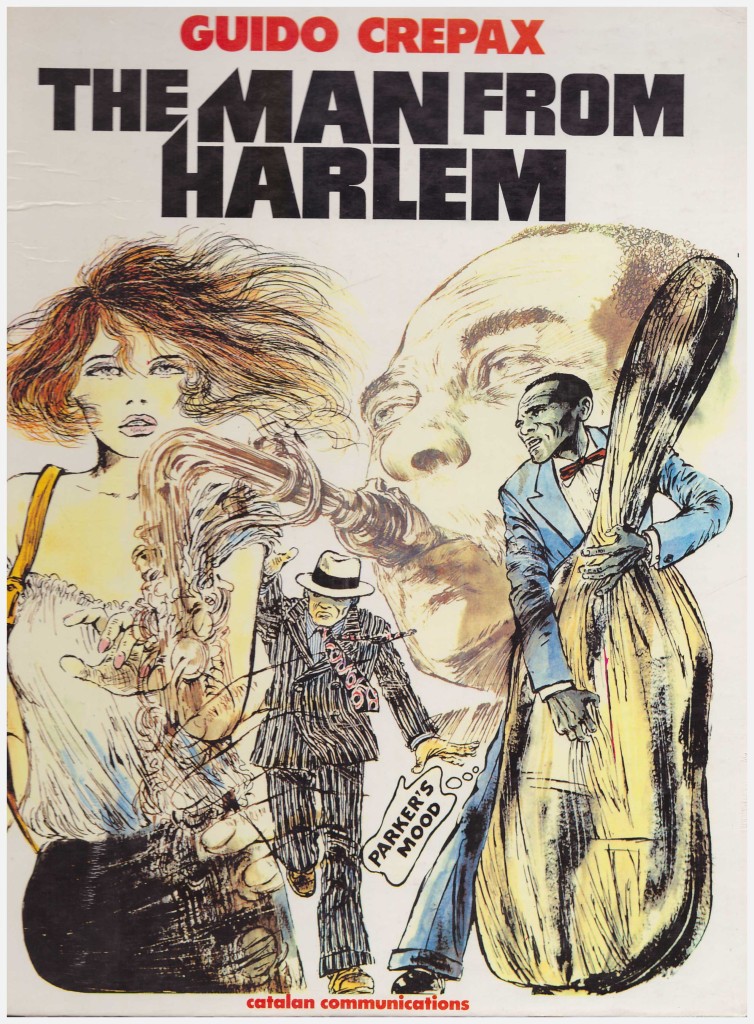

When it comes to English language translations Guido Crepax very much fell out of fashion after a mid-1980s heyday. Leaving aside the matter of a considerable erotic output presenting restricted opportunities in English, it’s easy to see why, as his strength is also his weakness. Simply put his art is utterly unique and instantly recognisable, his influences seemingly drawn from fine art, rather than previous comics material. His characters are expressionistic, viewing the world through heavy-lidded eyes, and created via loose, ragged lines. They wear their crumpled clothes, slouch and sulk, and are very rarely seen directly facing the reader. In a market that’s taken an age to move beyond an almost exclusive focus on superheroes, Crepax remains a distinctive oddity.

He studied architecture, but was a graphic artist before drawing comics, and among his notable illustrative work is a series of jazz album covers for Italian releases in the 1950s. The world of jazz held a fascination, and he feeds his love into The Man From Harlem, featuring a glimpse into the life of Little Johnny Lincoln. Little Johnny plays bass in a jazz band, and on the way to the gig one night in 1946 he punches out a guy chasing a white woman, Polly, through Harlem. The white knight in him doesn’t realise the trouble he’s just set loose, compounded when he takes Polly home to protect her.

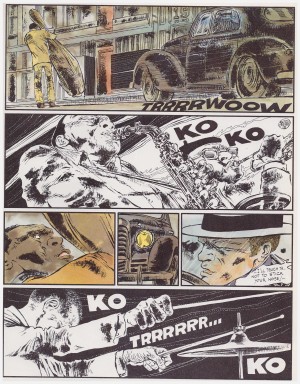

It’s a simple story underscored by the times, into which Crepax throws all the elements he loves about the era. We have boxing, photography, the mean streets of New York, glamorous dames, and hoods. Most of all we have jazz. Little Johnny plays it, and it’s the soundtrack to the times, the area and his life. Crepax signifies this by punctuating the narrative with panels of musicians performing, naming the tunes, and replicating that soundtrack for the reader.

His other storytelling methods are consistently unconventional and innovative, starting with the page designs. A half page illustration is separated from the remainder of the page by a thin strip of cameras clicking and flashing. He uses montages, diagonal panel separations and at times of greatest stress those jazz numbers come thick and fast. Lincoln is beautifully characterised by the art alone, almost always in motion, and seemingly only at peace when playing his bass. Yet, for someone so highly regarded, Crepax draws some odd bodies and poses. This isn’t just a matter of style, as there’s no consistency. A very prominent illustration has Polly draped alluringly, half sitting on a bed, yet her torso’s as long as her legs. A dozen pages later she’s standing and talking, oddly compressed with her arm bent back at a very uncomfortable angle.

The wonder is very illustratively weighted. Crepax is a spartan and emotive storyteller, and while his visual depiction of emotion is exemplary, his dialogue can be leaden. An interlude representing a century of racial oppression features almost clumsily, having little bearing on the wider plot, and the issues it highlights have already been covered in terms of social inequality and fear.

One further warning. Racial tension was ingrained in 1940s New York, and Crepax uses the derogatory language endemic to the period. This may be cause for offence today.

In 2016 Fantagraphics began a series of curated collections gathering Crepax’s complete output, and The Man From Harlem will eventually feature.