Review by Ian Keogh

There are some ideas that are just so obvious once someone’s smart enough to point them out. John Ostrander’s introduction credits then DC publisher Paul Levitz for noting that Superman’s adopted family are Kansas farmers, and Ostrander, who’d already planned a western, might want to backtrack through the generations.

So it is we meet Silas and Abigail Kent in 1854, along with their teenage sons Nathaniel and Jebediah. The family are introduced doing the right thing, scaring off a couple of bounty hunters who’ve chased escaped slaves into what’s now free territory. Shortly thereafter Silas and his sons move to the state of Kansas, and the story is told via the letters sent back to Abigail, and those to other family members. As the introduction mentions, letterer Bill Oakley put in a real shift designing the different fonts.

Ostrander’s introduction noted he intended to establish that Superman’s sense of justice was a family trait, so he reinforces this throughout, and he also salts the story with real people. These aren’t just the frontier heroes whose names have been passed down the ages, although they put in an appearance, but people whose work resulted in legislation, or that opened eyes. The problem is that it occurs so often that the Kents encountering the fruits of Ostrander’s research bogs down the narrative as they’re shoehorned in, each requiring an explanation. Some do have a bearing on the plot, William Quantrill and Jesse James in particular, but fewer historical figures, no matter how worthy, would have made for a more interesting story.

Weaving his characters into historical circumstances, Ostrander delivers a sprawling family saga with soap opera elements spanning two decades from 1856, and takes his cast in some unpredictable directions while supplying a distinctive voice for everyone whose letters relate the plot. He finds a clever way of working in the Superman chest emblem, has a down to Earth attitude regarding mythologised events, and a highlight is a character irrevocably sucked into events beyond his control. Disagreements about the justification for slavery run through the earliest sections of The Kents, prompting almost all the conflict. Ostrander conveys this well, and his abhorrence at the practice comes through, while later in the book his cast are wrapped into the equally regrettable deceitful treatment of the Native American population.

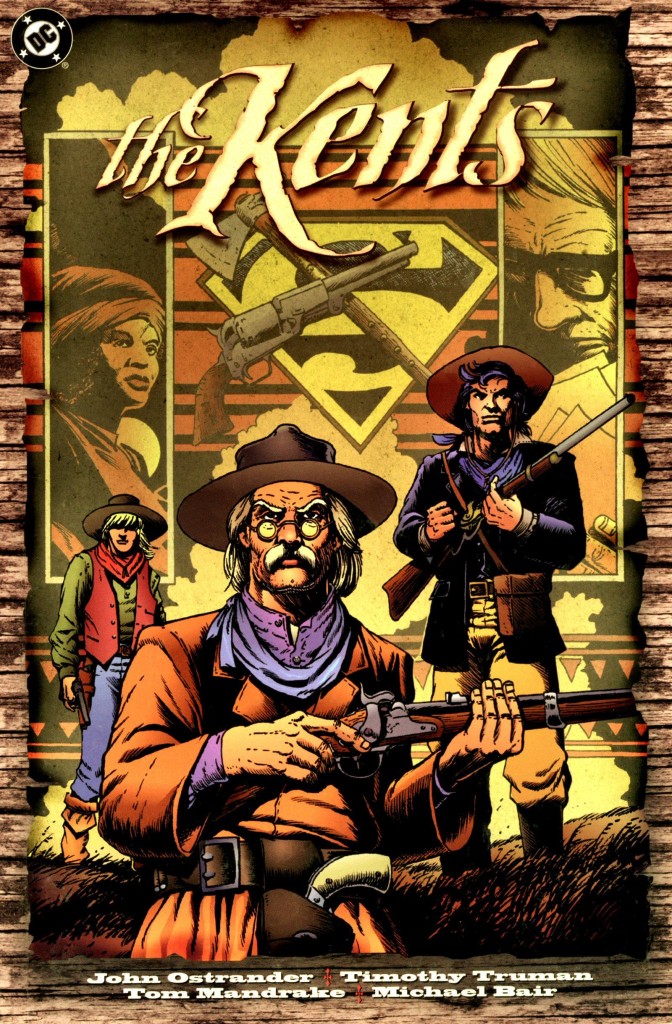

Tim Truman pencils two-thirds of the book, bringing a lived-in look to Missouri rabble-rousers, and frames his panels as if they’re overlaid on an illustration, which is a pleasant effect. His style contrasts that of the equally good Tom Mandrake who completes the book. Mandrake has a nobility and flourish about his pencils that also brings the cast to life, but in a different manner.

The Kents is an ambitious work, a graphic novel equivalent of How the West was Won, compressing its narrative slightly more. By what’s an excellent conclusion some Kents are established in Smallville and the future is nigh. For all the scope, The Kents is a dull read in places, mostly over the opening third of the book, but the plot tightens as the book continues. It’s not for everyone.