Review by Graham Johnstone

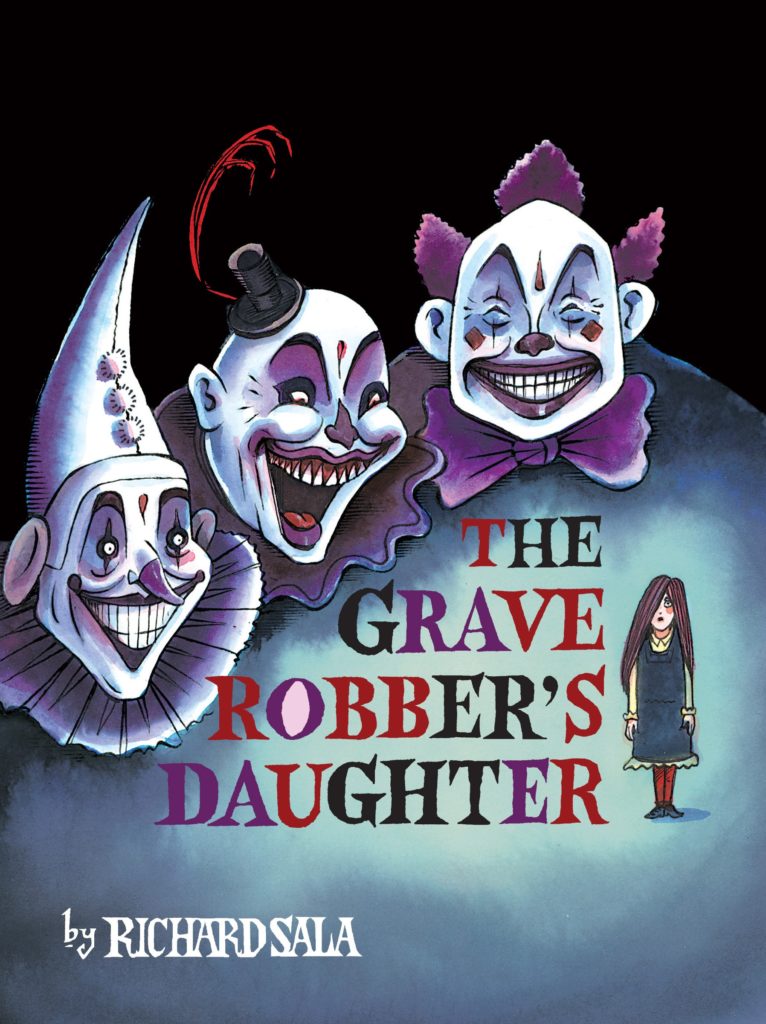

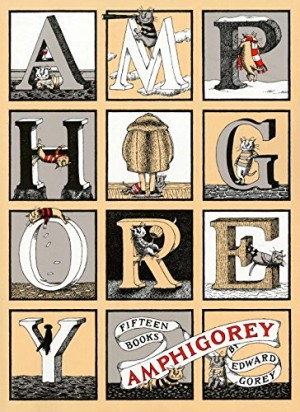

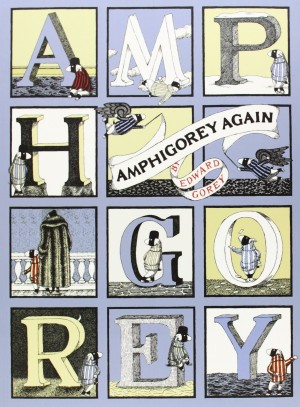

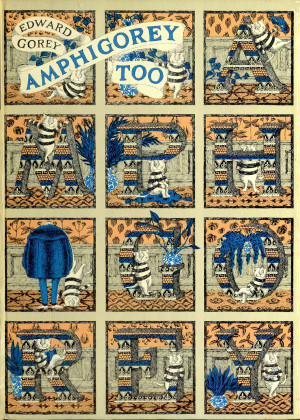

The cover of The Grave Robber’s Daughter teases its contents well. The title evokes both the supernatural and the domestic, while the clowns evince both the sweet and the demonic. The eponymous daughter is similarly ambivalent: a waif fatale we might say, her anachronistic attire pointedly signalling the unsettling Victoriana of Edward Gorey.

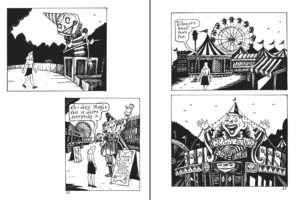

Sala is a sucker for schlock horror, which he both celebrates, and sticks pins into. The Grave Robber’s Daughter begins with young Judy’s car breaking down, necessitating a hike to the nearest settlement. This turns out to be a fairground, populated only by adolescents and the aforementioned clowns. The phones are all dead, and the cars gone, ensuring – true to form – no means of communication or escape. If that sounds somewhat Scooby Doo, it’s surely deliberate as Sala’s work is highly inter-textual. His set-ups may be familiar, but he takes them to unexpected fictional and philosophical destinations. For example in horror stories, adolescents, particularly those straying from adult authority, are often the prey, but not in these pages. Neither are they, here, the white knights riding into town like the Scooby gang in their Mystery Machine. Instead, they’re trapped in some notion of adolescent happiness that surely can’t last forever.

The story unpacks like a set of Russian dolls, with multiple tellers of stories that contain further tellers and stories. For example, the ring-leader of the young people tells Judy how he overheard the grave robber tell his daughter how his work led him to a spirit of the dead; who in turn tells her story… and so on. This unreliable narration, fragmentation, and general maximalism, is all part of Sala’s post-modern, meta-fictional, mischief-making with the machinery of story. A first glance reveals recurring genre elements and ironic humour, but a deeper look highlights the formal and narrative range within Sala’s deceptively consistent oeuvre. However, this literary depth doesn’t detract from the sheer delight of Sala’s books. He’s a confident story-teller, with fun ideas, grotesque horror/humour, snappy dialogue, and brisk pacing.

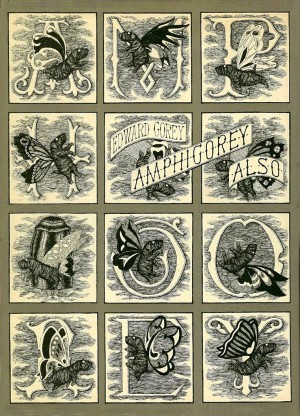

As an artist, Sala has a flair for simplification, gentle caricature, revealing posture, and telling expressions. He savours the settings of sideshow and cemetery, carny tents and crooked trees. He’s cultivated an ink technique that evokes old master engravings, and illustrations for gothic thrillers, yet, achieved in a way that’s assertively modernist. His lines create illusionistic tones and textures, while asserting their identity as ink on paper. Sala’s best pages rank with anything in comics. Other pages, though, can look more workaday, even hasty. On close inspection, some of the figures are graceless, the penmanship lacking the precision and finesse of his finest. Sala typically favours dip pens, suitably retro devices that offer unequalled modulation of line weight. Here, though, the lines look more mechanical – most noticeably on Judy’s bare pins (pictured), which seem less shapely than legs seen in Peculia. That may disappoint inking connoisseurs, but doesn’t impede the story.

This not Sala’s absolute best, but as always, it’s an artful and entertaining romp, which repays careful reading, and rereading. Next off his drawing-board would be Delphine, collected in 2012.