Review by Frank Plowright

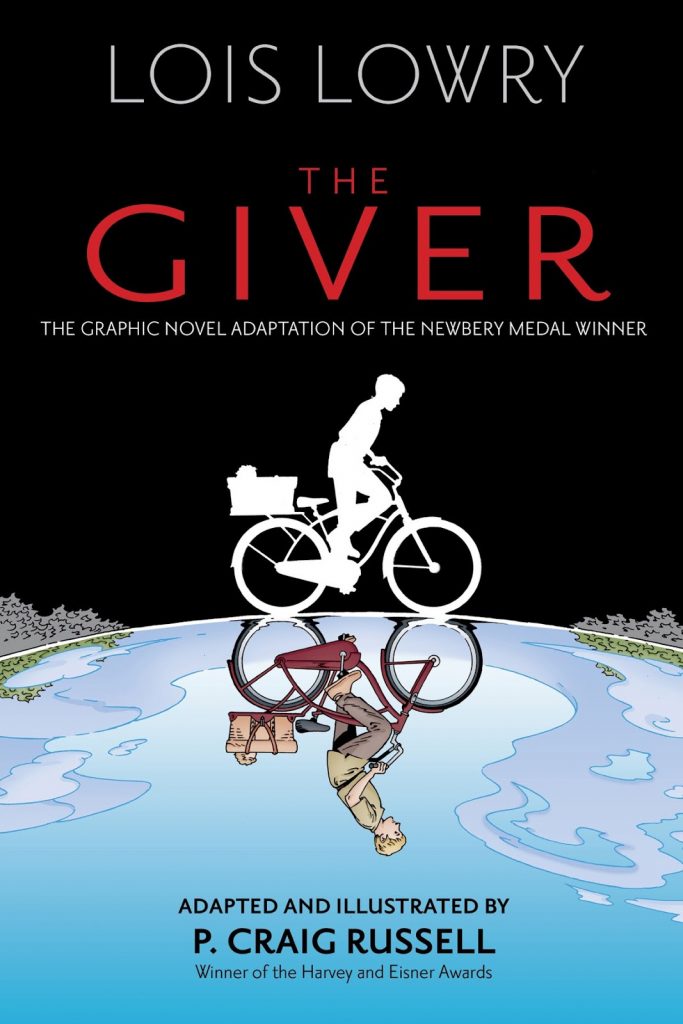

Lois Lowry’s young adult novels all have points to make about society and the way we see other people. They’re accessible, intelligent and credit readers as having capability for independent thought to sift the information and make up their own minds what’s good and what isn’t. Since its 1993 publication The Giver, the first of a quartet, has been targeted for banning on numerous occasions.

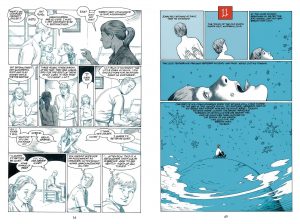

It opens in what seems an idyllic society where respect for others is considered paramount, people are encouraged to discuss their feelings and address negative issues, and children’s wellbeing is prioritised. However, early on in P. Craig Russell’s adaptation there are signs that a utopian society has a downside, with emotion suppressed and society governed by inviolable rules. Colour is used very sparingly over the opening chapters, which may be assumed to be Russell using the brightness and lack of shade to make a point. He is, but the metaphor is Lowry’s from the novel, and becomes clear later when colour plays a part.

The focus is Jonas, about to become twelve, when he’ll participate in a public ceremony where the work he’ll do for society is to be decided. The society in which Jonas is being raised has been long established, and he’s very keen to obey rules, but readers soon come to realise some of those rules are inhumane and abhorrent. Establishing that ensures The Giver is continually tense, and that’s broadened by frequent references to people being “released” without explaining the term, cleverly leaving readers to imagine the worst.

Jonas is chosen to be a Receiver, which in practice means bit by bit all the memories of the world as it once was are transferred to him, and only he and a few others have access to old books. Becoming a repository opens up all sorts of contradictions within what he’s been brought up to believe is right. These are subtle, the ills of the world as it is presented alongside what’s been more questionably sacrificed.

While Russell draws much of the adaptation, exquisitely as always, he’s chosen his collaborators well. The Giver’s separation of experiences lends itself to other artists being involved without threatening the narrative. In fact, given some of the points Lowry makes, participation of others could be considered essential, but the work of Galen Showman and Scott Hampton used to present experiences of the past has a simplicity and elegance that matches Russell’s pages.

Dystopian fiction never seems to account for children being the genetic soup of preceding generations, so allocated infants always slot in smoothly with families who understand them perfectly. Anyone who’s ever adopted knows how false that is, so it’s pleasing to see The Giver tackle that head on. By the end Jonas has also learned what the process of releasing involves, the example most distressingly featuring his father, as the result of severe emotional suppression is shockingly seen.

Although only the opening volume, The Giver doesn’t require a sequel, all its points strongly made in a satisfying, if never cheery story, although the ending offers hope. Russell’s career has almost exclusively concerned adaptations, and his version is sensitively presented keeping the intentions intact. How long will it take before it also attracts calls to be banned?