Review by Frank Plowright

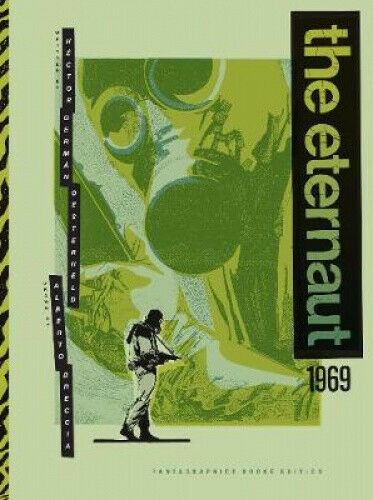

As explained in the introduction, The Eternaut’s original run was considered a seminal piece of Argentinian fiction a decade after its conclusion, while the country was still experiencing turmoil and political instability all those years later. It was under those circumstances that Héctor Germán Oesterheld chose to revisit his creation, this time in the company of artist Alberto Breccia.

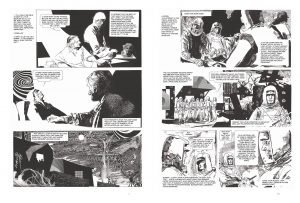

Rather than a continuation, this is a compacted reworking of the earlier story, produced as comic pages in three page instalments rather than as a three tiered comic strip. Breccia is a far more textured artist than Francisco Solano López, and more given to flourishes adorning a story, and Oesterheld recognised an alternate version could have equal validity. He’d also developed as a writer, and there’s a greater poetry about the narrative captions, which capture a fatalism not always apparent in the original version.

As before, Oesterheld supplies a very personal opening, Breccia picturing him at work as the Eternaut manifests at his table with the story of his experiences ready for the telling. In its essence, the plot doesn’t depart greatly from the original, a strange snow descending on Buenos Aires, killing those who walk out into it, and necessitating the hastily cobbled together protective suit providing the story’s defining image. However, Breccia changes the goggles for a gas mask, something more practical in the circumstances, but lacking the visual immediacy of the original. The philosophical pondering, existential questioning and political allegory is raised, with Oesterheld considering South America’s place in the world, and Argentina’s within that. The militia of this story is far harsher, and there’s an extremely rushed ending.

Superhero comics thrive on the retelling of iconic moments, but a complete retelling of the same story is rare, and The Eternaut 1969 perhaps shows why. There’s no denying the greater insight and passion to Oesterheld’s script, nor his recognition of how it could be adapted as more directed commentary, and he’s working with an even better artist. There’s some remarkable art among the abstracts and tones, but Breccia’s approach isn’t that of the action artist, and the whole is nowhere near as compelling as the original version. The tension of the adventure strip that was the engine of the original story is neutered, replaced by a ghostly echo. The readers of the time apparently felt the same way, and while Eternaut 1969 is an ambitious attempt to extend the boundaries of comics, it leaves the audience behind.