Review by Ian Keogh

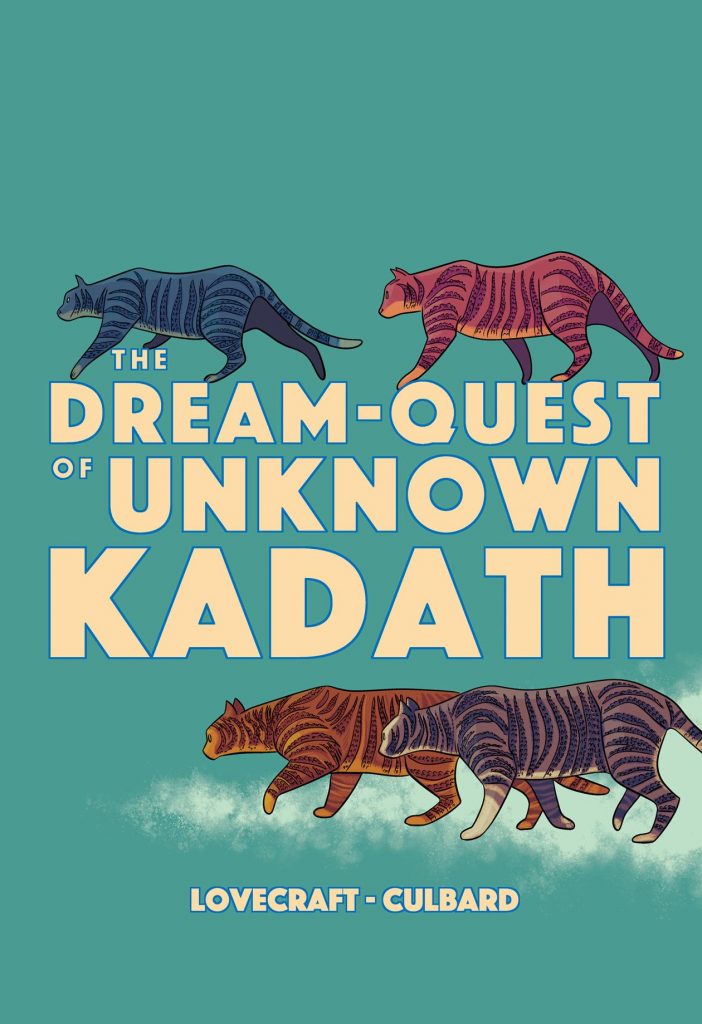

Not every author is the best judge of their own work. H. P. Lovecraft wrote The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath and discarded it, not even bothering to make revisions to a first draft. Like The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, it was only published posthumously, yet is regarded by fans as a supremely imaginative blending of fantasy and horror.

Randolph Carter features in several of Lovecraft’s stories, and is considered by scholars to be Lovercraft’s alter-ego, conceived at the time when he was also a struggling writer and experiencing vivid dreams. In what’s one of Carter’s longest stories he strives to reach a place he’s dreamt of since childhood where he will meet the gods, having an awareness that while he’s dreaming, the consequences of his dream may harm him in reality. With that threat hanging over him we wonder whether Carter is inordinately brave or inordinately foolhardy.

In his search for Kadath, Carter travels through many different landscapes, each with their own threat, and each drawn differently by I. N. J. Culbard within his own precise style. Lovecraft’s fiction perpetuates tension via what’s hinted at, but barely seen, and this story does so more than most, everyone Carter meets warning him and relating their experiences. Culbard mixes often dry conversations with flashbacks over the opening third of the book before being able to expand the scenery and the personnel, making good use of colour.

On several occasions Carter apparently awakens, only to realise he’s still dreaming, and beyond those opening conversations his experiences have a greater dreaming quality, with sense sometimes sidelined. It’s a difficult story to adapt, but Culbard’s restrained manner sustains the tension. Almost everything is delivered as matter of fact, whether it’s an ordinary ship sailing a sea or the creepy eyes beyond a door. To supply the story in action fashion would destroy the cultivated mood, and Culbard helps out with some of Lovecraft’s obscure references to other stories by noting the events of Pickman’s Model, for instance.

For all the skill of the adaptation, though, Lovecraft’s story is one that promises much and delivers little, although the influence has trickled down into numerous fiction narratives, so short of altering it considerably, there’s little Culbard can do about that. Carter learns something from someone in one place, journeys elsewhere and picks up another hint. Described horrors are largely unseen, and those presumed to have seen them have never returned. It leads to an ending that’s drily funny, but perhaps not the most satisfying after all that’s been suggested. Perhaps Lovecraft was right to consider this an exercise not for publication.