Review by Frank Plowright

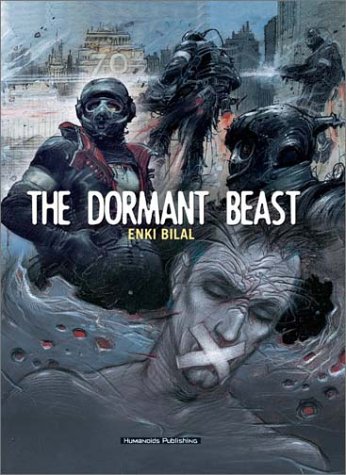

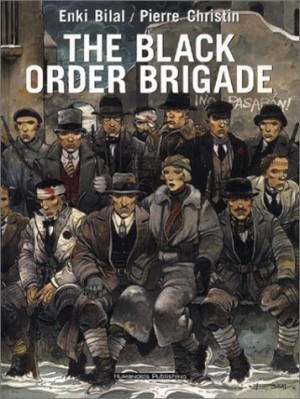

By the time Humanoids translated The Dormant Beast in 2002, Enki Bilal’s stock in the USA had fallen considerably from its 1980s peak, when his every appearance in Heavy Metal was celebrated, and he was a rare European creator whose work also sold in English. His most famous works were his collaborations with Pierre Christin (see recommendations), after which Bilal began publishing solo material and moving into film illustration, eventually also making his own films, but he never stopped drawing comics.

While serving up a complete story in itself, The Dormant Beast is actually the opening part of a four volume series produced over a decade, never completely available in English until Statix Press combined them in hardcover as Monsters. This opening chapter is a daunting proposition, events and characters never entirely explained, although dots can be joined in what seems to be Bilal processing what happened in the land of his birth through science fiction. Yugoslavia fractured into several countries in the early 1990s amid atrocities and war. What resonates even more now is the use of a religious fundamentalist group of terrorists, not just Islamic, but an aggregation of religious hardliners from across the spectrum.

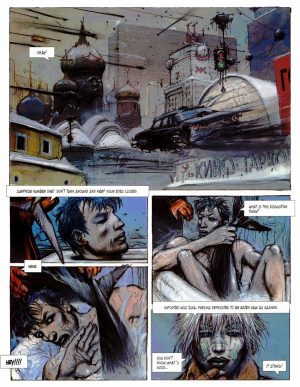

As the plot almost defies an intelligent description, perhaps the best place to start is with the art, which is prime Bilal in terms of technique. His people are distinctive and noble, some hard edged, others conventionally attractive, portraits a speciality. His visual world-building is breathtaking. Bilal sets his story in a 2026 that he knew in 1997 would be in advance of ours technologically, but one that’s already seen better days. Flying cars are converted from classic models, and never explained cables string the skies, while a scientific genius uses computerised flies as a method of control. Wherever possible Bilal avoids movement, telling his story in illustrated panels, accompanying caption boxes as common as dialogue.

The opening sequences are led by Nike Hatzfield, who we come to learn is investigating his own death, yet is also working his memory backwards, having reached eleven days after his birth in Sarajevo as the story starts. He’s one of three people from the same ward connected with each other, all of whom have a pivotal role as events unfold. The political background is one of conflict, a primary generator being one Optus Warhole. He represents the dense conceptuality apparent throughout, incredible science combined with artistic inclinations seemingly created to the template of a James Bond villain.

This is a graphic novel that needs commitment from the reader, as while Bilal eventually pulls most threads together, it should be stressed that’s not the same as revealing everything. It’s hard going, with most readers likely to struggle to get the gist of what’s happening, but for fans there’s seventy pages of stunning art.