Review by Karl Verhoven

The first thought prompted by the title is whether Frank Miller really worked on enough Spider-Man stories to warrant this publication. It turns out he did. Six are included, four of them longer than the usual 22 pages.

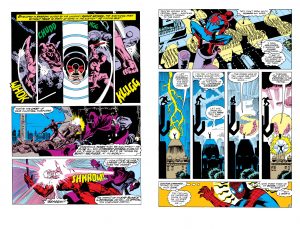

Miller’s earliest Marvel work was on Spider-Man, illustrating a two part story immediately prior to becoming Daredevil’s regular artist, and getting in some practice as Daredevil drops by to help a temporarily blinded Spider-Man. Bill Mantlo’s story is melodramatic cliché: “Daredevil you don’t understand! I may see again… I may not, and while I “rest” the Masked Marauder’s getting ready to strike!”. Any novelty is purely Miller’s sense of visual creativity, displayed by the sample page, despite it featuring Daredevil.

It’s astonishing to see how far that visual creativity leapt in just a year when Miller draws the 1980 Spider-Man annual, guest-starring Doctor Strange. The importance of atmosphere has been a lesson taken in, and Miller makes the most of then relatively new visual effects, but most surprising is how so much of the art references other artists. Steve Ditko’s designs are the most prominent, but the constant downpour comes from Will Eisner, some action sequences look like Jim Starlin, while chapter separating illustrations draw on church architecture. The story’s daft fun.

Infatuation with the borderless colour overlay continues in the introduction of future X-Man Karma, Chris Claremont validating the filled thought balloons by her adjusting to Spider-Man’s body and power set after taking him over. More impressive now is the grainy effect used for depth on the flashback sequence, and a page of vertical panels. The credits are ambiguous, but if taken at face value Miller seems to have had plot input into both this story and the previous one, although they bear few hallmark grace notes.

The final two inclusions provide a study in contrast and an object lesson about the importance of artwork. There’s not actually much to choose between the plots, both relying on thought balloons and an element of contrivance, but that isn’t the conclusion you’d reach from just looking at them. Best standing the test of time is the closer in which O’Neil provides a script playing to the strengths of what Miller was then achieving in Daredevil, and it’s greatly helped by the sympathetic gritty inking of Klaus Janson. For the other Miller only writes a smart, twisting crime drama featuring the Purple Man, an old Daredevil villain Miller didn’t use during his run there, and the trouble he causes assorted heroes. Herb Trimpe draws that as standard 1970s Marvel work, efficient storytelling with no sparkle, whereas Miller’s pages for O’Neil’s story ooze atmosphere. Trimpe’s Kingpin resembles a Weeble, wobbling but not falling down, while Miller’s Doctor Octopus, on paper an even more ridiculous looking villain, is threatening. It’s because Miller rarely shows him full figure, instead accentuating the sinuous nature of his pliable electronic arms, using silhouettes and shadows effectively. There is some dodgy figurework, but the noir atmosphere ensures the story still holds up. O’Neil’s narrative device of repeating newspaper front pages is also clever.

While a collection of Miller’s Spider-Man assignments might be seen as desirable, in practice it doesn’t meet expectation, and it’s Miller’s art pulling it up to average overall. The collaborations with O’Neil are both enjoyable, but too much else is ordinary. Nicely freshened-up digital copies of Amazing Spider-Man Annuals 14 and 15 are your best bet.