Review by Fiona Jerome

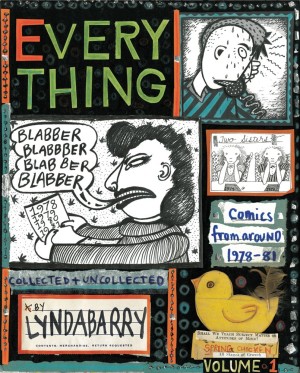

Robert Crumb is one of the most important and influential artists to have emerged from comics, with a career spanning decades. He has always been in at the start of movements, from the early rumblings of the Underground comix scene to the sudden interest in autobiographical comics in the 1980s. As an artist he has never ceased to take on new ideas and evolve. It’s therefore entirely fitting that Fantagraphics should devote a series to publishing every scrap, strip and cover they could locate by the great man but, for the average reader, it doesn’t always make for satisfying reading.

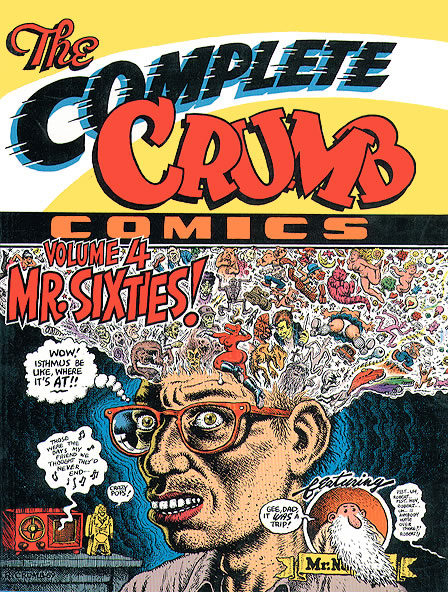

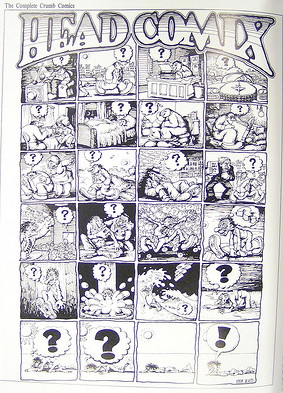

Volume 4 features material from late 1966 to 1967 when Crumb was still drawing greetings cards to make ends meet – they make up part of the colour section in this volume, along with the winsome ‘Sad Book’, and a handful of comic covers, some of which never saw light. Aged 22 Crumb was at a crossroads: his marriage had broken down, his ex-wife Dana had gone back to Cleveland, and he was experimenting with drugs, which is reflected in the weirder and rather darker nature of some of his strips, particularly those from Zap Comix dating to late 1967. He was becoming more recognised as a cartoonist, and in the middle of the year his cartooning style suddenly shifts up a gear from the scratchy and often cramped panels of his earlier work to a much more finished, rounded style. It displays the first signs of the cross-hatched approach to inking that would become his signature in later years.

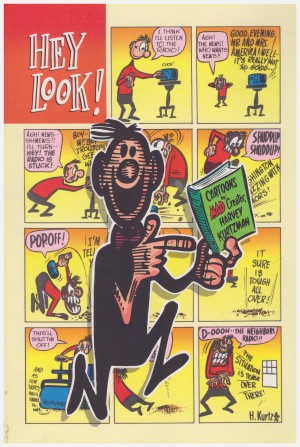

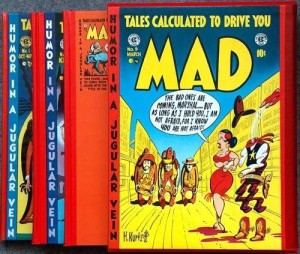

Still taking digs at the hippy scene he’s now irrevocably associated with, this period saw a great deal of creativity in Crumb’s work, with lots of new characters being experimented with then discarded and a number of seminal strips, such as ‘I’m A Ding Dong Daddy’ and ‘Keep On Truckin” appearing in Zap. Among the new raft of characters was Mr Natural, a send up of our desire to find ourselves via the egos (and purses) of gurus and philosophers. On the one hand Crumb’s strong sense of satire and the ridiculous, nurtured by his love of Mad magazine growing up, allowed him to ridicule the excesses of the counter-culture, while his free-form responses to drug culture gave the Underground movement some of its most enduring characters.

There are some of Crumb’s best early strips here, and there is some completely forgettable material. While it’s interesting to see the cartoonist’s ideas and visual style developing, it remains an unsatisfying read because of the patchy quality of the contents and the fact that you only really need to see half a dozen of Crumb’s greetings cards to get the idea of what they’re like. Not seeing hundreds will not leave you unable to appreciate the development of his style one jog. Scholastically ‘Complete’ is great, but for the general reader a more edited approach would be more appealing.