Review by Frank Plowright

This fifth collection of Sergio Toppi’s beguiling short stories offers an even greater timespan than the previous Cradle of Life, the earliest dating from 1975 and the latest from 2011, with the other four representing every decade in between. This time it’s Jason Shawn Alexander’s turn to provide an introduction extolling Toppi’s astonishing compositional skill and his virtuosity with lines.

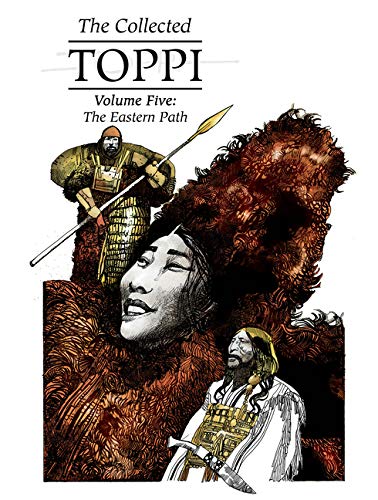

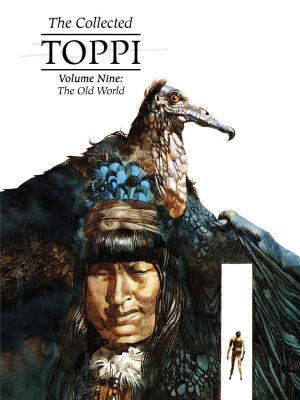

The cover features studies of what are revealed inside to be Taiga people, as three of six stories largely consider areas of Russia. As is customary for Toppi, they’re all period pieces, defined by the dress of the Western intruders and their technology into areas where clothing and custom is traditional. As ever, myth and legend play large parts, as matters to be respected, although Toppi is willing to exploit superstition. This is in the 1994 story of Kas-Cej, of an out of favour university archaeologist sent to a remote area of Siberia, allegedly on a mission of utmost importance, and one that results in a life changing experience.

Toppi’s theme is almost always the clash of the traditional with the modern, but not the modern of our era. He obviously prefers to draw the past, but the storytelling method of focussing on what at the time was considered the height of progressive thought or technology reflects back on our era and the fallacies of our certainties. It’s emphasised through a cynical boatman whose livelihood is disappearing in the 2011 piece, which could be read as Toppi’s own eulogy. The art is slightly looser than earlier stories, and features a neat visual metaphor on a tragic closing page.

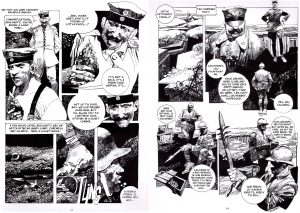

Otherwise in artistic terms, as shown by the sample pages, there’s little difference between the quality of the 1976 story of a German soldier in the World War I trenches, and the following story from 2004 featuring an Italian in much the same circumstances. The major difference is the more illustrative page composition, the Toppi of 2004 having long discarded conventional panel to panel storytelling in favour of less contained drawing, sometimes montages, but still conveying what’s necessary without any difficulties.

World War I also features in the final story, yet looks back further and is closely tied to the other stories by a consideration of what war releases. In each case Toppi provides a literal and supernatural face to events, yet the window dressing differs, attached to three separate people and their demons. The final visitation is the most memorable, in part due to the rich character portraits and the slightly more exotic setting. However, this is the first of the Toppi collections to date where standards drop a little. The drawing is marginally weaker in places, and the reworking of the same theme is a fault of the curation, the second story produced fourteen years after the first, and the third fifteen years after that. The Eastern Path is still a master at work, and still exceptional, just not quite as exceptional as volumes one to four.