Review by Ian Keogh

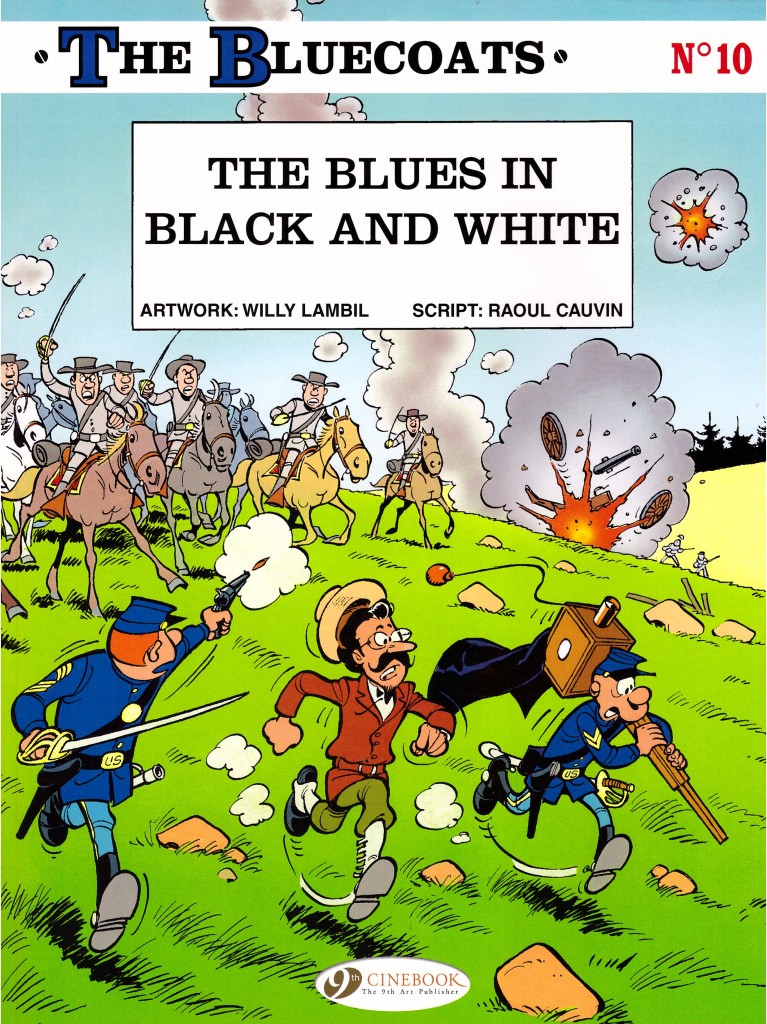

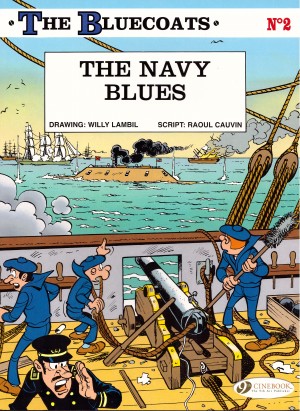

It’s difficult to imagine an era when photography was new, largely unknown and strange, yet so it was in the early 1860s, around twenty years after Henry Talbot had developed his photographic printing procedure. A decade later George Custer would be the most photographed man of his era, but The Blues in Black and White introduces Matthew Brady to the world of the Bluecoats. As in Lucky Luke, the inclusion of real people can be a distraction, but Raoul Cauvin strikes the right note with Brady, conveying his ambitious and hard-working personality, and his determination to be the pre-eminent documenter of the Civil War.

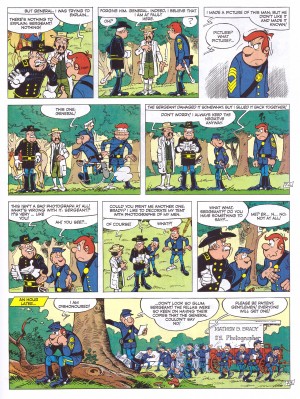

Cauvin’s storytelling is clever. He manages to construct a series of slapstick sequences that none the less result in heroic images, and because this is largely aimed at young readers (although is equally enjoyable for adults) he underplays the message about manipulation. It’s a theme toyed with throughout the book, with an iconic photograph of Captain Stark leading his ragged and wounded troops back to camp accompanied by dialogue about how they’ll charge again after reloading. Regular Bluecoats readers are aware of Stark’s reckless disregard for the lives of his troops. Toward the end Cauvin and Willy Lambil include a parade sequence of the type now more likely to echo the excess of North Korean militarism than glorify the forces of right, and again underlines this in subtle fashion.

In a book that concentrates on images, Lambil produces his usual strong work. He’s very effective in packing his panels with detail, yet without ever having them seem crowded, or drawing the eye away from what needs to be seen. As ever, the story is punctuated by wonderful half page illustrations that don’t hold back on showing the true cost of war, yet do so in a manner consistent with the age group at whom the stories are aimed.

The supporting cast are beginning to be fleshed out a little more from their previous single characteristics, Stark as an example now exhibiting additional glory-hunting tendencies, and Cauvin’s plot ensures Blutch has his dearest wish. He becomes a civilian again, although this doesn’t displace him from the dangers of battle, and we also see a version of Abraham Lincoln who’s far removed from the great statesman he usually appears as.

That The Bluecoats can be read in any order is underlined by the conclusion to this book. The next album both in terms of original European publication dates and Cinebook’s numbering is The Cossack Circus, by which time everything has been re-set.