Review by Ian Keogh

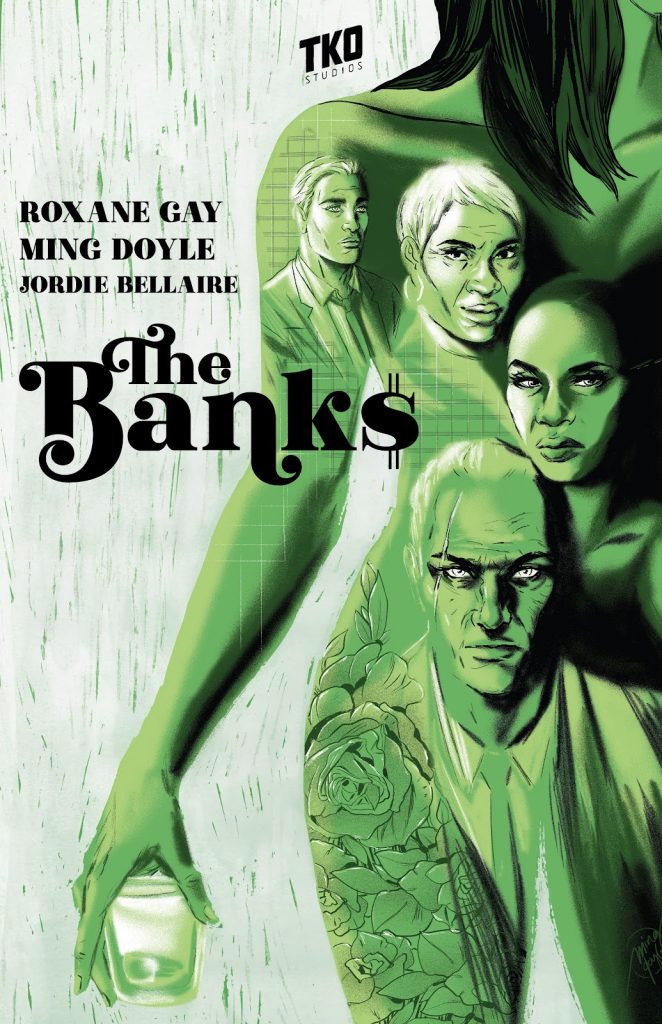

Celia Banks is employed with no sense of irony as an investment banker, and as The Banks opens she believes the hard work she’s put in over the years is about to pay off with a company partnership. For her that’s the culmination of a journey pulling herself away from the unashamed criminal activities of her mother and grandparents, whose successful thieving ensured she had the best start in life. Celia’s about to be disappointed, and it’s a hard lesson in the distressing way the world still works if you’re black or a woman. Still, it opens her eyes, and she’s always got the family trade to fall back on.

In between showing how Celia is shafted over the opening chapters, Roxane Gay takes several enjoyable journeys back into the past, supplying detail about how Celia’s grandmother Clara and her grandfather operated in the 1960s and 1970s, and how they were eventually also shafted. It didn’t stop Celia’s mother Cora from following in their footsteps, and as the family is explained, Gay also explains why they’re all in favour of taking Celia up on her suggestion. Then she throws in the complications.

The Banks is a crime caper dependent on us liking the criminals and feeling the victim deserves what’s coming to them, and on those counts Gay succeeds over the first half. Ming Doyle brings the cast and periods to life, occasionally a little stiffly posed, but convincing. She doesn’t take shortcuts, largely keeping the viewpoints at distances needing half and full figures to be drawn, and keeps a fair amount of space around them, although the houses could do with more detail to seal the illusion of people living in them. They tend to look more like show houses for sale.

While The Banks is efficiently run through, sustains tension and has an empathic cast, it’s also too obviously formulaic, and while the relationship between Celia and her family is strong and convincing, there’s not enough bolstering to other people. Celia’s boyfriend features in one nice scene, but is otherwise just there to throw a strop every fifteen pages (although not without justification) and her reactions to that are hardly realistic. When toward the end he’s needed for something else, it doesn’t ring true, and neither does much of the ending. Gay has some points to make about investment bankers and money laundering, but they’re hammered home, and in order to provide the ending she wants she overlooks numerous pitfalls concerning what’s likely to happen when one pokes a bear with a stick.

In the end it’s the family interactions and trips to the past that have the strength, and too little of the remainder convinces.