Review by Graham Johnstone

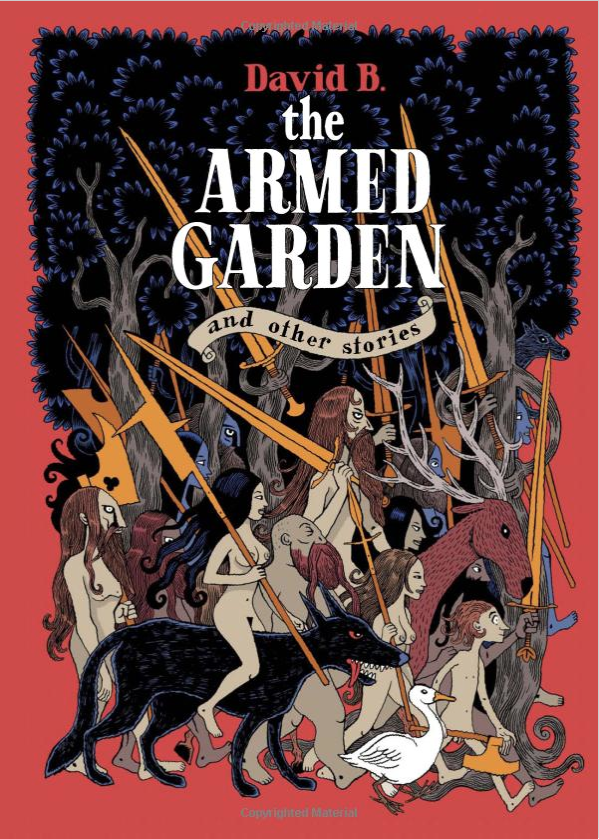

The Armed Garden comprises three thematically linked ‘graphic novellas’ by French creator, David Beauchard, better known as simply David B.

These stories may seem entirely from the realm of mythology and folk tales, but in fact have their roots in documented people and events. The common theme is visionary individuals promoting radical (if not necessarily sound!) challenges to the religious and social norms of their times. These are no peaceful mystics, these ‘prophets’ build armies of followers, and pursue their causes with military might.

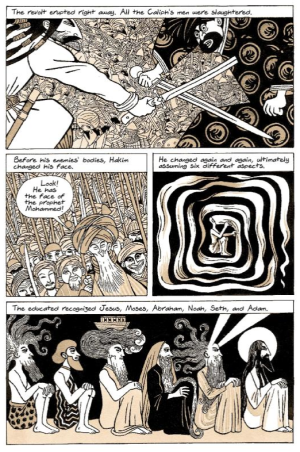

‘The Veiled Prophet’ is based on 8th Century Hashim Ibn Hakim, who became known as Al-Muqanna – ‘the veiled one’. Beauchard locates his story chronologically in the era of the Tales of the Arabian Nights – more correctly known as the 1,001 Nights. Stylistically it belongs there too. As it’s told here, a shape appears in the sky, thought to be a legendary and portentous bird. It turns out to be a huge piece of cloth which wraps itself around the face of a lowly dyer. People identify his obscured face, first as an earlier local hero, then as various prophets, and ultimately able to assume a variety of forms. He’s said to be able to call forth an army of the martyred dead.

The other two stories are set in the Hussite Wars of rival Christian sects in 15th Century Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic). In ‘The Armed Garden’ the blacksmith Rohan has a visitation that convinces him he is a modern Adam. He gathers followers around a belief in Garden of Eden innocence, nudism, and opposition to property and hierarchy. Yes, like the hippies in USA and elsewhere 500 years later! Inevitably this brings them into conflict with those of different views.

‘The Drum Who Fell in Love’ is made from the skin of a fallen leader, whose consciousness lives on in the drum. At first it’s drummed to rally troops to battle. It’s channelling of the dead leader is powerfully effective, leading to great victories, but the drum grows tired of this and yearns to hear a different tune. Eventually a young woman from the camp is drawn to the drum, providing a more tender relationship.

These are powerful narratives, full of arresting imagery, and the perfect vehicle for Beauchard’s art. His clarity and elegance of visual communication, here, recalls the orderly flatness of Persian or Ottoman miniatures. He adds to this a seemingly effortless knack for apposite symbolic representations. He doesn’t just show us the story: he expresses the ideas.

Take for example the depictions of the Veiled Prophet. At first we see the veil spiralled around Hakim floating like a maze or trap (pictured). Then it becomes a turban, growing larger until it has a fortified city on top. Later the cloth snakes out in tendrils towards various figures whose forms he might take, then becomes rolling hills, and then a raging flood. In another panel we see his torso filled with “the martyred bodies of all those oppressed”.

It’s beautifully rendered in black and washes of umber. The nearest comparison, in both imagery and rendering is innovative British creator Ed Pinsent, though in comparison B is smoothed off for mainstream consumption.

This is an accomplished creator at the height of his powers. The content also has few comparators outside his own work. You can see it in the historical/fantastic interludes of his autobiographical Epileptic, and the Middle East focus of the first story points toward his more documentary Best of Enemies.

Each of these stories also appeared in Mome – in volumes 4, 3, and 12 respectively.