Review by Frank Plowright

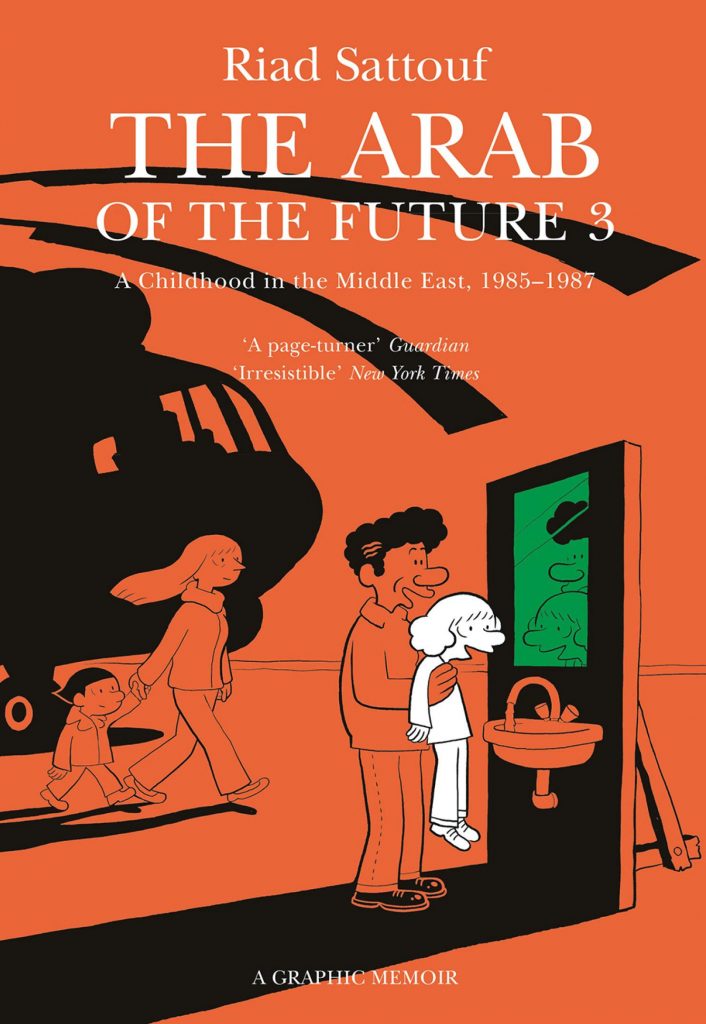

Riad Sattouf’s two previous volumes recalling his eccentric childhood in Syria have been both evocatively shocking and delightful, and this continuation matches them. It’s another tour-de-force.

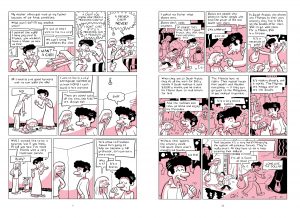

As seen on the sample art, Sattouf’s father still straddles a hypocritical line concerning his professed beliefs, which amount to paying lip service to all kinds of notions, the priority being those that give him an easy life. For the most part he manages to appease everyone other than his wife. The opening pages show how the now seven year old Riad has also learned techniques enabling him to survive at school, and his greater sensitivity to the world around him enables him to note the growing chasm between his parents. His more practical mother now realises dreams of the future aren’t reliable prediction, and Sattouf underlines this neatly as his Moslem cousins are disappointed that Santa Claus has ignored them despite his insistence Santa visits every well behaved child.

Sattouf’s cross-cultural and often contradictory influences are well explored. Five pages are spent on his startling experience of seeing the John Milius Conan the Barbarian film, not considered a masterpiece by the wider world, yet as seen at seven an influence that’s remained with Sattouf. As previously, the reality of his life almost matches the brutality of Conan. A page describes a punishment handed out, where transgressors are bound to a chair, and held down while the soles of their feet are beaten as hard as possible. This doesn’t occur in a jail, but in Sattouf’s primary school. It’s a punishment he only avoids via his father bribing the head teacher. Circumcision is a continuing theme, and the horrors aren’t confined to Syria. Sattouf’s mother constantly yearns for a move back to France, yet while there on holiday equally disturbing things occur.

Neat evocative cartooning has been the hallmark to this point, and sees Sattouf through the entire series, endearing little notes pointing out extra items of interest in the detailed panels. He has a magnificent talent for expressive people, his own younger self stoic amid some great expressions on others.

Reading about Sattouf’s father continues to be gruesomely compelling in the manner of viewing a car crash, and what had previously been admittedly large eccentricities here cross a line. It’s reported in the usual dispassionate manner, but the inescapable conclusion is that he has undiagnosed mental problems. Despite continuing to catalogue disappointments about his father, Sattouf almost makes us feel sorry for him when detailing why one of his business ventures is failing, but quickly hauls that back by revealing how compromised he really is. In previous books Sattouf’s mother has been a weaker character, but she comes into her own here, with more pointed demands and frustration with her whimsical and secretive husband, although some elements she presumably consents to are glossed over and puzzling. Having militated to leave the remote village in Syria where they live, by the book’s closure in 1987 she’s got what she wished for, but not exactly in the way she would have wanted. Sattouf concludes the recollections of his childhood by covering the years 1987-1992.