Review by Roy Boyd

Spoilers in review

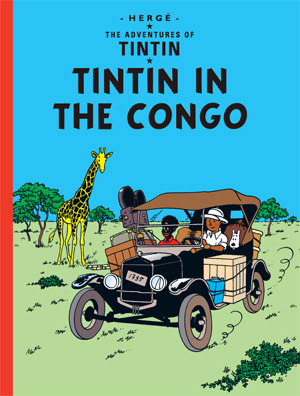

Tintin in the Congo, the second book in the series, is much more polished than the boy reporter’s maiden adventure, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The destination, a Belgian colony, was chosen yet again by Hergé’s editor and mentor, Abbé Wallez, a ‘traditional’ Catholic priest. It goes a long way to explaining the book’s politics.

The opening scene features a cameo by Thomson and Thompson, even though they would not appear properly until the fourth adventure, Cigars of the Pharaoh. They’d snuck in (alongside an appearance by Hergé himself) when he redrafted and coloured the entire book in 1946, cutting it down from 110 pages to the by-then standard 62-page format of the other books.

Michael Farr, Tintinologist, (and, yes, that really is a thing) has called this book ‘essentially plotless’, and he’s not wrong. Like the preceding adventure, this is just a series of incidents very loosely strung together. Some are quite amusing, but the most apparent thing to any contemporary reader is how wildly offensive many of them are.

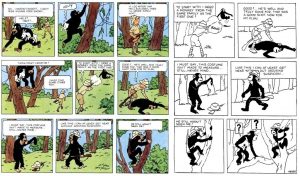

This includes, as a fairly typical example, Tintin shooting and skinning a ‘monkey’ (actually an ape) so he can wear its skin as a disguise. And this is just after he’s accidentally shot a whole herd of antelope, mistakenly thinking he was shooting at the same animal over and over again. He also removes the tusks from a dead elephant. To be fair, Tintin hadn’t actually killed it, but it was not for lack of trying.

There is some attempt at plot when it’s revealed, during a couple of noticeably wordy panels, that the Chicago gangster Al Capone (the only historical character to actually appear as himself in a Tintin book) is behind the attempts on our hero’s life and the diamond-smuggling operation that Tintin has stumbled upon. Clearly Hergé was letting the world, and probably Abbe Wallez, know that his next adventure would take Tintin to America, somewhere his creator had wanted to send him from the outset.

This – along with the Soviet adventure – were books that Hergé considered “youthful transgressions”. Because of it’s troubled past, this was the last book to be made available in English. A facsimile of the book’s original black and white 1931 version (considered less offensive than the later version) appeared in 1991, before the 1946 version finally appeared 2005. This was with later changes, including the redrafting of a scene that originally depicted our hero drilling a hole in a rhino’s back, inserting a stick of dynamite and blowing the poor beast to pieces.

This isn’t a bad book, and the artwork is pretty good. However, the depiction of the local population and the animal cruelty spread liberally throughout the book make Tintin in the Congo a difficult read. Strangely enough, in spite of its blatantly colonial and paternalistic content, this is the Tintin book that has proven most popular in Africa, especially the French-speaking countries. And the truly astonishing amount of controversy surrounding the book also helped push it into Amazon’s top-ten bestseller list and saw retailers like WH Smith and Waterstones placing it alongside graphic novels rather than children’s books. It’s also been sold with a protective band to ensure that the unwary aren’t exposed to attitudes that would nowadays be considered offensive, and a foreword inside does the same job.

So, probably not one to buy for your young niece or nephew at Christmas, but a title that has many enjoyable slapstick moments, if you can put aside modern sensibilities and appreciate it as a product of its time.