Review by Frank Plowright

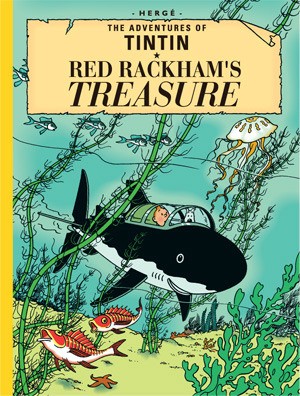

An assured Hergé was by 1942 confident enough to plot a story that was almost entirely set-up for the following volume Red Rackham’s Treasure, yet to disguise it so this wasn’t obvious, and enable it to be enjoyed individually. With the exception of Land of the Black Gold, pairing volumes in this manner was a pattern he’d follow for the next decade.

This was the first Tintin story created during the German occupation of Belgium during World War II, which removed Hergé’s option of basing his villains on real world figures. It may have seemed an unwanted restriction at the time, but it forced Hergé to become a better creator. He was also helped in achieving this by the uncredited Jacques Van Melkebeke, a writer and cartoonist employed by Le Soir. Van Melkebeke had collaborated with Hergé on two Tintin plays, and research indicates he contributed considerably to plotting The Secret of the Unicorn.

The book is a farewell to Tintin the detective, the genre that had perpetuated him since the earliest days. He’ll remain plucky and resourceful, but adventure will supplant the detection altogether (apart from a brief reprisal as years later Hergé subverted his earlier detective material in The Castafiore Emerald). The detection here concerns multiple stolen wallets, secret pieces of parchment, and clues to the location of vast plundered treasure, and unusually the exotic location so integral to Tintin stories is supplied here by a trip through time. Captain Haddock acts out the adventures of his remarkably similar looking ancestor while Hergé intersperses this with depictions of the 16th century action.

When asked, for a long time Hergé would refer to this book as his favourite Tintin adventure. His meticulous eye for detail and setting is displayed throughout from the exceptionally well recreated old ships to the first appearance of Haddock’s later estate Marlinspike, based on the Loire valley chateau of Cheverny. For all the clever interweaving of the threads, his plotting still hadn’t completely attained a matching sophistication, as convenience dictates too many elements. There’s the simultaneous arrival of three market place purchasers setting the story in motion, the odd method of leaving a bequest, let alone why a seemingly fit and healthy Sir Francis Haddock never retrieved the treasure himself.

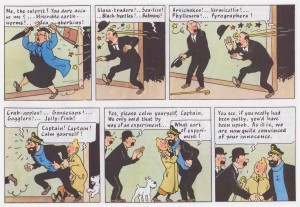

That last point is addressed in the sequel, but to carp about this is to focus too much attention on irrelevance in the face of a cracking good story. The art is fantastic, Thompson and Thomson are provided with a series of well-worked gags, Tintin’s imprisonment and escape is thrilling, Haddock is at his endearing best, and the minor character of Aristides Silk and his obscure hobby is inspired. Only one more character was required to elevate Tintin to his best, and he’d arrive in Red Rackham’s Treasure.

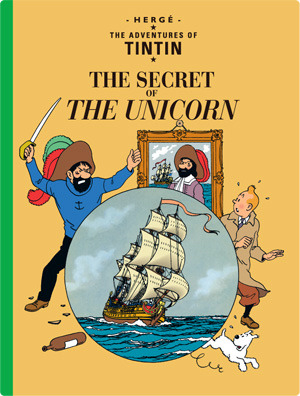

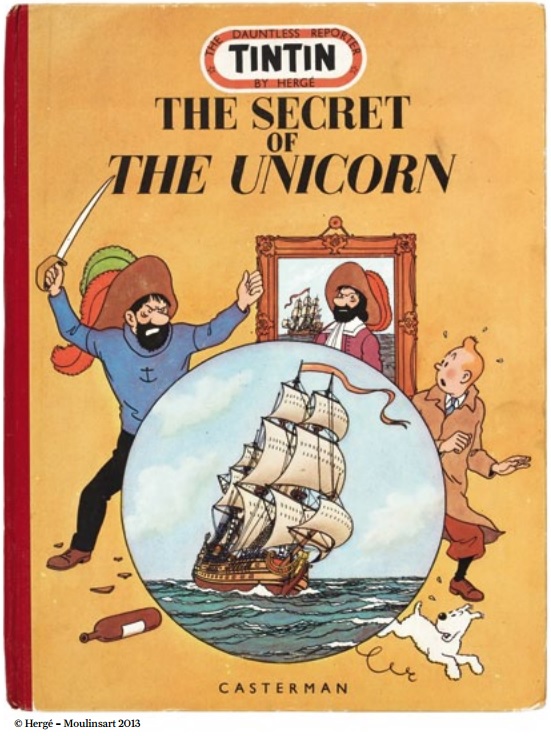

Secret of the Unicorn and its companion volume were the first Tintin books to be translated into English, as “The dauntless reporter Tintin by Hergé”, but these 1952 volumes from French publisher Casterman weren’t successful. Improved translations by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner in 1959 had a far wider appeal, and English language editions have remained in print ever since.