Review by Frank Plowright

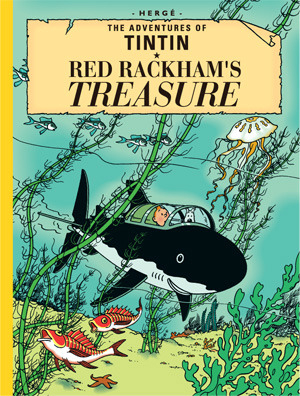

The Secret of the Unicorn depicted how Tintin and Captain Haddock learned the location of his ancestor’s sunken fortune. Red Rackham’s Treasure concerns the retrieval, introduces the final essential member of the Tintin cast, Professor Cuthbert Calculus, and definitively changed the theme of Tintin.

Tintin’s introduction established his adventurous streak, but his escapades to this point were detection-based. There was always a puzzle central to the plot and Tintin followed the clues until it was solved. The location of Red Rackham’s treasure is the conundrum of this volume, but it’s not overarching, as the bulk of the book hinges on the exquisitely worked interaction between the main cast members without a villain or cause to propel the narrative. And while there’d always been a humorous element to the series, from this point there’s a full commitment.

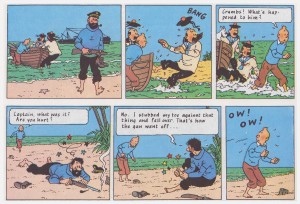

Hergé’s plots had frequently fallen back on the absent-minded professor as provider of an essential clue or information, and he’d presumably concluded a regular would aid his narrative. The result is a comic tour-de-force. Calculus distils the essence of absent-minded professors used throughout Tintin. He’s introduced in an astonishingly fine slapstick sequence as he guides Tintin, Captain Haddock and Thompson and Thomson around his lab, displaying his inventions as mishap follows mishap. His introduction is also perhaps the best example of his other major comic characteristic, deafness, with which he erodes all opposition. In addition to being deaf, Calculus is completely incapable of reading body language, blithely ignoring any impediment to his desires.

Calculus upps the gag quota, but he’s not the sole source. It’s as if Hergé aimed to provide a small dose of relief for the occupied Belgium of 1943 when this was originally serialised, with a constant stream of funny material. Haddock’s lust for drink is a richly mined seam, as is his rich language, Thompson and Thomson are more comically inept than usual, and it’s a rare page that doesn’t contain at least one good joke.

As ever, the art is stunning, Hergé expending ever more effort to ensure the accuracy of his details. The ship on which the cast sail to the Caribbean was depicted from a model constructed after extensive research at Ostend docks. Red Rackham’s Treasure contains a panel noted by Hergé as one of his best ever drawings. It depicts Haddock striding ashore as Tintin and the Thompsons drag the rowboat from the sea. Biographer Harry Thompson notes the value was in simultaneously covering several necessary actions in one illustration, so rapidly moving the plot forward. And that plot has some spectacular twists, not least the finale. This is not far shy of Hergé’s first masterpiece.

In 1952 Casterman took a punt at expanding their audience by issuing English editions of The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure. Improved translations by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner in 1959 had a far wider appeal, and English language editions have remained in print ever since. Red Rackham’s Treasure heads the sales list for the most popular Tintin book.