Review by Karl Verhoven

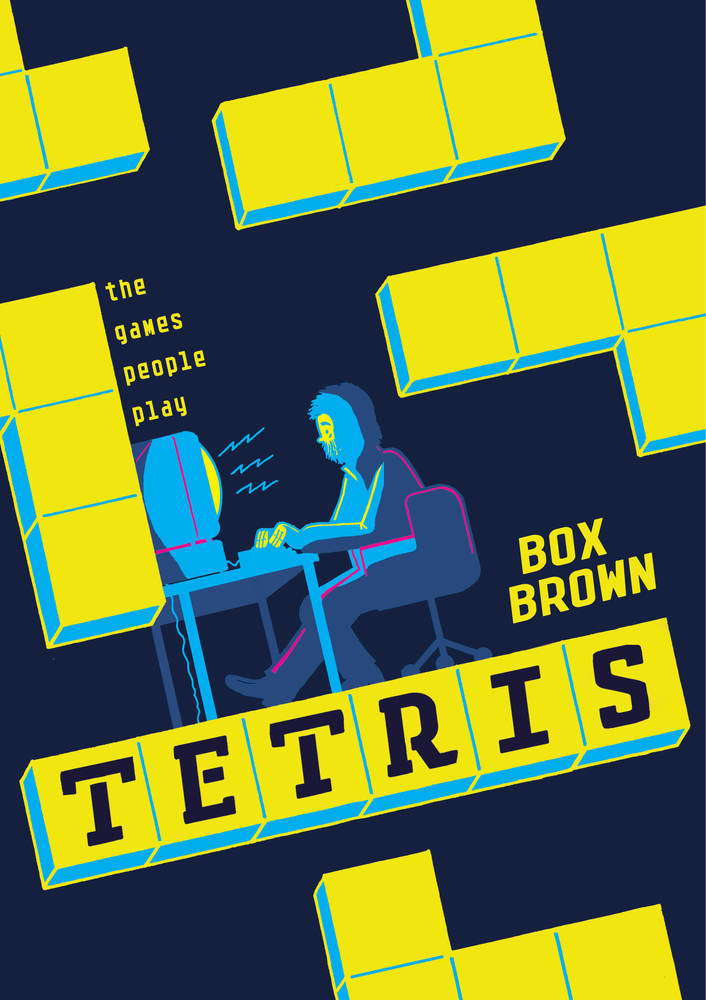

There can be very few people in the Western world who’ve not idled away time playing Tetris, but in case you’re one of them, it’s an addictive computer game involving slotting various shapes together as they descend from the top of the screen. This moving version of pentominoes was created by Russian Alexey Pajtinov in 1984, and this graphic novel promises the creation of Tetris, the battle for it, and its social impact.

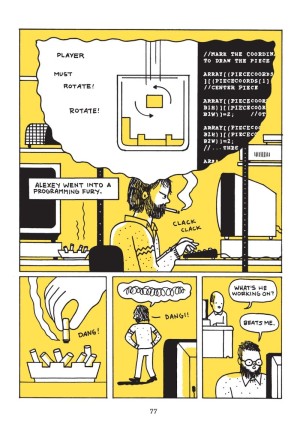

Author Box Brown casts a far wider net, gathering in the human need to play games and its existential purpose, the long and confusing marketing negotiations and assorted other worthwhile sidetracks. Pajtinov created the game while studying at the Russian Academy of Science, frequently considering our place in the universe until late in the night in the company of his friend Vlad Pokhilko. He justifies his interest by observing that games and sport have informed life since the earliest days. From there Brown explores the application of skills learned while having fun, and vastly more.

To anyone with a curious mind, the handicap of Brown’s very basic art is rapidly overcome as he throws in one fascinating anecdote after another. The creation of Nintendo, for instance, the company most associated with Tetris, began as an attempt to perpetuate Hanafuda, during a period when certain card games were outlawed to prevent gambling in Japan. Organised crime found a method of circumventing this using the hand-stencilled Nintendo cards, and for decades until the 1960s the company’s output was exclusively Hanafuda cards. Brown diverts skilfully for thirty pages to chart the growth of Nintendo, and by the time he works his way back to Pajtinov there’s almost a disappointment.

As much as Patjinov, this is the story of two other a remarkable people. Dutch businessman Henk Rogers might have a cowboy’s name, but he was astute and persistent, and seemingly charismatic enough to cut through the harsh façade of Russian negotiation. That was eventually led by Evgeni Berikov, a man able to remain unswerving in the face of considerable state pressure and to think on his feet. Bit players include the later thoroughly discredited newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell.

It would have been nice had Brown included more dates, nailing down, for instance, when Pajtinov sent his dos-based version of Tetris to Hungary from where the global spread really began. He parallels the distribution of the game via world events, but this still requires some co-ordination on the part of the reader until we reach 1988. He also has a problem relating the legal complexties of a case involving Atari and Nintendo in the book’s dryest section.

Throughout the graphic novel as the value of Tetris to others continually inflates, Pajtinov becomes an increasingly irrelevant figure, not in line to benefit from his creation beyond a one-time beano to Las Vegas. By relating the story of Nintendo developer Gunpei Yokei, Brown highlights the contrast, but another failing is never really clarifying Rogers’ conscience. He considers Pajtinov a friend, so how does he reconcile making millions from his creation while Pajtinov requires a day job after moving to the USA? “Wanna see photos of Henk’s place in Hawaii?”, asks Pajtinov, while Rogers later offers “You know I could help you guys out with money any time” after Pajtinov and Pokhilko have founded their own business in Seattle. Rogers eventually does the right thing, but it comes across as a strange relationship.

What might be considered a graphic novel with limited appeal is consistently attention grabbing, but may have been more so had Brown surrendered the art.