Review by Ian Keogh

Back in the 1980s Alan Brennert was a positive rarity as a TV dramatist who occasionally slummed it in comics, never realising he was, in fact, a pioneer. That his first submission was selected to lead off DC’s 500th issue of Detective Comics underlines how the editors regarded his talent. He manages to combine mystery, a depth of characterisation then unusual, and interesting twists in a manner that few of DC’s regular writers could match. Perhaps writing for television and knowing his dialogue and situations would be acted out provided Brennert with an inherent advantage, and he also had the editorial advantage of being able to age the characters in something approximating real time. Hawk and Dove, teenagers in the late 1960s are in their late twenties when he teams them with Batman in 1981, and ageing is integral to a story exploring the loss of idealism and innocence.

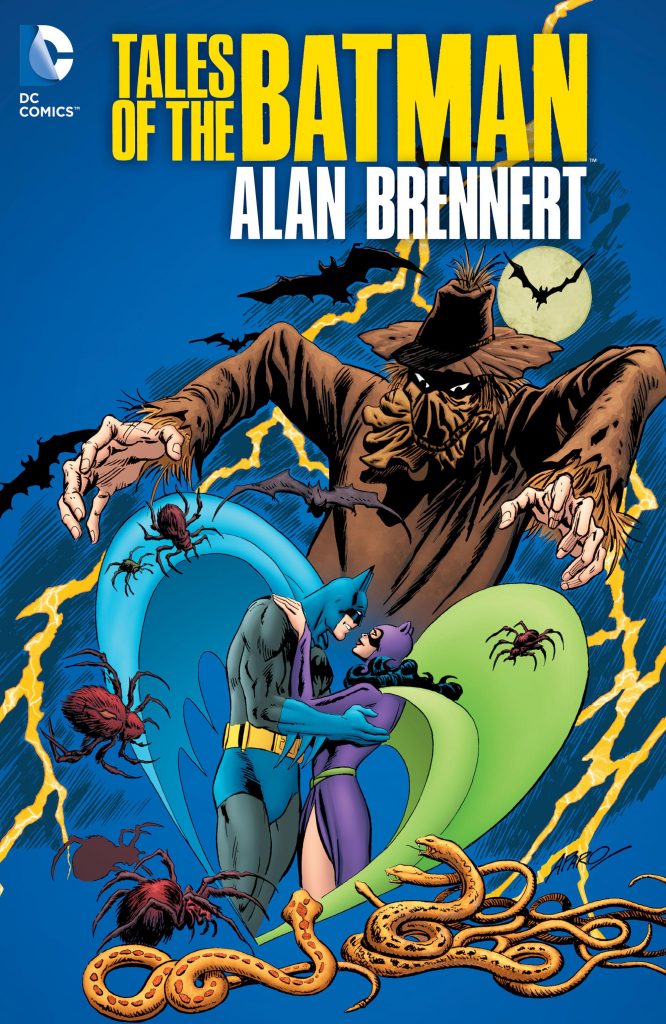

In his introduction Brennert writes of his childhood love of DC’s ‘imaginary’ stories, where alternate possibilities played out for superheroes. Given his opportunity, he produced several. The longest has Bruce Wayne in a world where Oliver Cromwell’s version of state puritanism spread well beyond England, extending to the 20th century. In this world Wayne’s parents are also murdered, but other circumstances prompt his evolution into Batman, and ‘Holy Terror’ is all the better for not improbably resolving matters shortly thereafter. That opening story toys cleverly with the ethical dilemma of Batman being given a chance to prevent the murder of his parents’ equivalents in another world, but will it thereby prevent the eventual manifestation of Batman? The most touching of these alternates spotlights the slightly older Batman of what was then categorised as Earth 2, telling the story of how this Batman met, romanced and married Catwoman. It employs the gimmicks of 1950s stories with a knowing wink, but allied with a greater realism. The introduction notes a scene indicating the toll Batman’s injuries have taken on his body, and scores points for Batman conceding a weakness and opening up. It’s sentimental without dropping into melodrama.

Brennert peppers his stories with guest stars, being fond of Justice Society of America members, but these are smoothly incorporated with purposes beyond nostalgia. Batwoman, Flash, the original Green Lantern, Robin, Starman, Wildcat and Zatanna all have decent roles. Brennert’s two non-Batman stories also feature. A great character study of Deadman was produced for a Christmas special, and there’s a run through of the 1940s Black Canary’s origin as she’s on her deathbed, also incorporating some good scenes with Green Arrow and Green Lantern. It’s very good.

When these stories were originally published they exuded sophistication compared to most monthly fodder, but the extra care Brennert took to convince is now far more common, and some elements have dated. Brennert was very true to the black or white character of the Creeper, and this leads to some predictive scenes of the hectoring TV commentators now prevalent, but the villain he and Batman face occupies far more space and is now better forgotten. Brennert’s scripts are also word heavy. It’s noticeable that several artists break the stories down into small and cramped panels to accommodate this. And this is a fine selection of artist, all good storytellers and all distinctive. Jim Aparo (sample art left), Norm Breyfogle, José Luis García-López, Dick Giordano and the combination of Joe Staton and George Freeman (sample art right).

Most of these stories stand the test of time, and at his best Brennert’s able to hone in on a topic and exploit the hell out of it.