Review by Ian Keogh

The Sandman followed the Chameleon, the Vulture and Terrible Tinkerer as Spider-Man’s fourth villain. Flint Marko was hiding on the beach at an atomic device test area when a tested device merged his molecules with sand, enabling him to switch back and forth, and transform parts of his body to sand. In introducing Sandman, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko cover this over an economical five panels, a cursory explanation all they believed necessary in 1963. While reprised in a couple of the subsequent presentations, it’s not an origin that’s been overly fleshed out. Tom DeFalco and Ron Wilson are the most detailed, adding to Marko’s pre-sand career, also factoring in a story by Roy Thomas and Ross Andru establishing that no matter what he’s done, he always visits his dear old mother on Christmas Eve.

When introduced Sandman was a relatively plain looking guy in a green t-shirt with thin black hoops that’s served him well ever since, which is just as well since it was transformed along with him. It’s something of a timeless look, and a rare instance where a Jack Kirby redesign in an attempt to jazz him up proved a mistake, although Lee and Kirby’s story is a good one. By that time Sandman had become a more familiar foe to the Fantastic Four as a member of the Frightful Four, not included here, the collection restricted to his solo appearances.

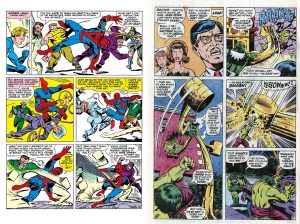

While Spider-Man fights him more than anyone else, to name the collection after him is slightly misleading as in addition to the FF he also runs up against the Hulk, and shares a pint with the Thing, without violence involved. While not every story sparkles, the Sandman poses an interesting challenge and his use keeps writers inventive. How to you defeat someone who can just change into granules of sand and be carried away by the breeze, reconstituting himself miles away? Yet also compact himself into something as hard as brick? More importantly, how can he be defeated without repeating a previous capture? It’s something already challenging Thomas in the 1970s, who produces an ending avoiding the problem entirely, repeated by DeFalco in the 1980s. By 1995 Kurt Busiek and Pat Olliffe resort to solution that probably wouldn’t have occurred to Lee and Ditko.

Lee has a hand in all the best content. He’s possibly only supplying dialogue over Kirby’s FF story, but it’s a humdinger, and will have you rushing online to discover how the cliffhanger ending was resolved. Sandman’s return in 1964 us in two parts, unusual for the time, when the pressure of being assaulted on all sides becomes too much for Peter Parker, who has other priorities, and quits as Spider-Man. Lee and Ditko exploit the melodrama well, particularly with an uncharacteristically cheerful J. Jonah Jameson sporting an ear to ear grin.

Also unusual is Herb Trimpe’s art on the Hulk appearance. His inventive storytelling methods over the first half have been influenced by looking at the work of Jim Steranko, after which he’s back to his usual style, but the interlude has layouts that stick in the head.

With the panels packed into the pages, the most recent story from 1995 (and that over a decade on from the 1982 Thing piece), and explanatory thought balloons aplenty, this collection may be too strongly rooted in the past for contemporary readers. Anyone who can overlook that will be able to while away a nostalgic hour or two.