Review by Frank Plowright

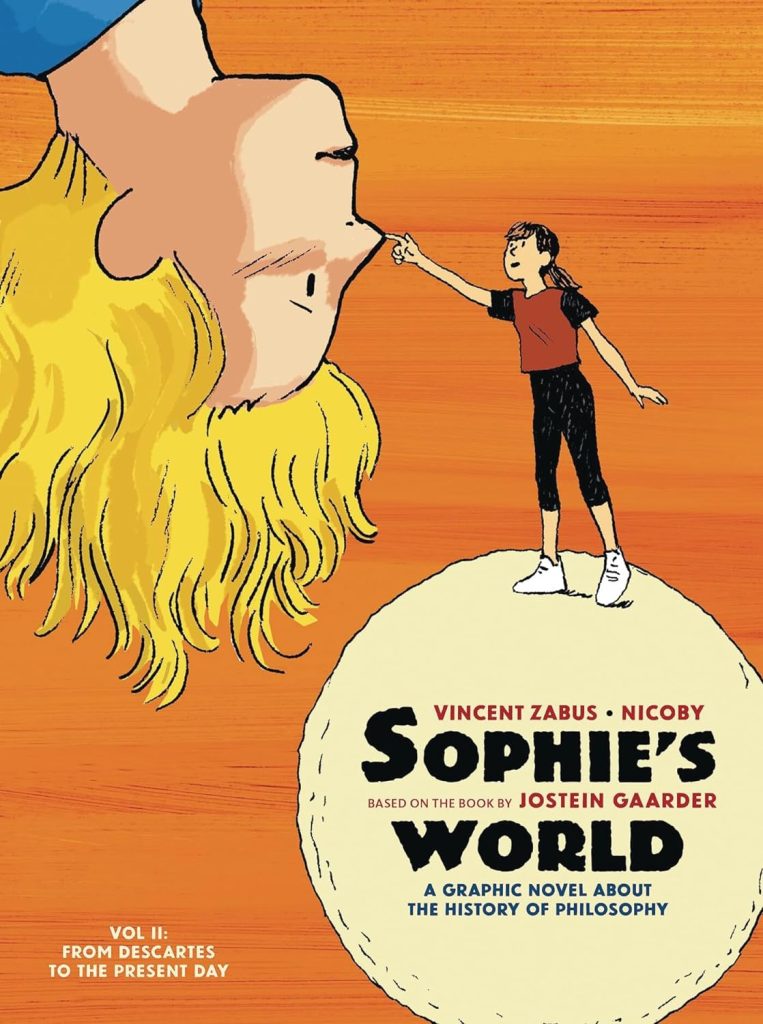

Vincent Zabus and Nicoby took on the immense challenge of transferring the bestselling Sophie’s World to a graphic novel format, eventually concluding two volumes would be required. From Socrates to Gallileo saw the teenage Sophie hearing a voice encouraging her to consider philosophical issues, and also educating her about the philosophers of the past. She eventually met her educator, and a natural break ended the first volume with Sophie’s realisation she’s a fictional character.

She spreads this self-awareness, which cleverly feeds into discussions about free will and pre-determination. The ongoing education takes picks up with 17th century French philosopher René Descartes. As we learn, he was the first to develop a system to categorise philosophies. He and others deliver their theories via visually stimulating sequences, which is important as unless you’re enthused by philosophy it can be a very dry and ethereal subject. Illustrating concepts of rationality isn’t an easy task, solved by Nicoby via lively characters moving about to make their points, and the possibilities open with the revelation of Sophie being fictional, as the all-powerful author makes their presence felt. As Sophie explores the world, the impossible begins to happen, yet if all things are possible, how can anything be impossible? Let’s just say she’s not previously encountered brick walls randomly appearing, and Nicoby’s visuals expand comically to encompass this new feature. There’s also some impressive playing about with the form of comics for a few pages midway through.

A feature of Jostein Gaarder’s original novel is the application of philosophical concepts to the advent of climate change, which is transferred to the adaptation. As Greta Thunberg is mentioned it’s logical to assume the original statistics from the 1990s have been updated, but they still make for concerning reading, such as learning humanity collectively consumes in six months what is produced in a year. It’s also worth noting this isn’t a direct adaptation of Gaarder’s novel, as to make it work in a different format Zabus and Nicoby have had to replace some of the original text and insert themselves into the narrative, and scenes with Nicoby’s daughter effectively counterpoint the philosophy.

Philosophy may seem the province of abstract thinkers, but from around the early 18th century it began to have far more social application as the rights of man came under consideration, and Western society gradually divorced from the control of the church. Names familiar from other spheres such Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx connect directly with philosophy and their influence on our lives has been immense.

Sophie’s World is exceptionally well presented. Explanations of complex theory are supplied in terms that a smart person in their early teens can understand, yet has value well beyond that audience, and the frequent use of slapstick humour and a perpetuated mystery ensure this is no dry experience. It is, however, an extremely dense graphic novel, possibly best read a chapter at a time to permit some thought about what’s been imparted. Anyone with any vague interest in philosophy is recommended Sophie’s World as a starting point.