Review by Frank Plowright

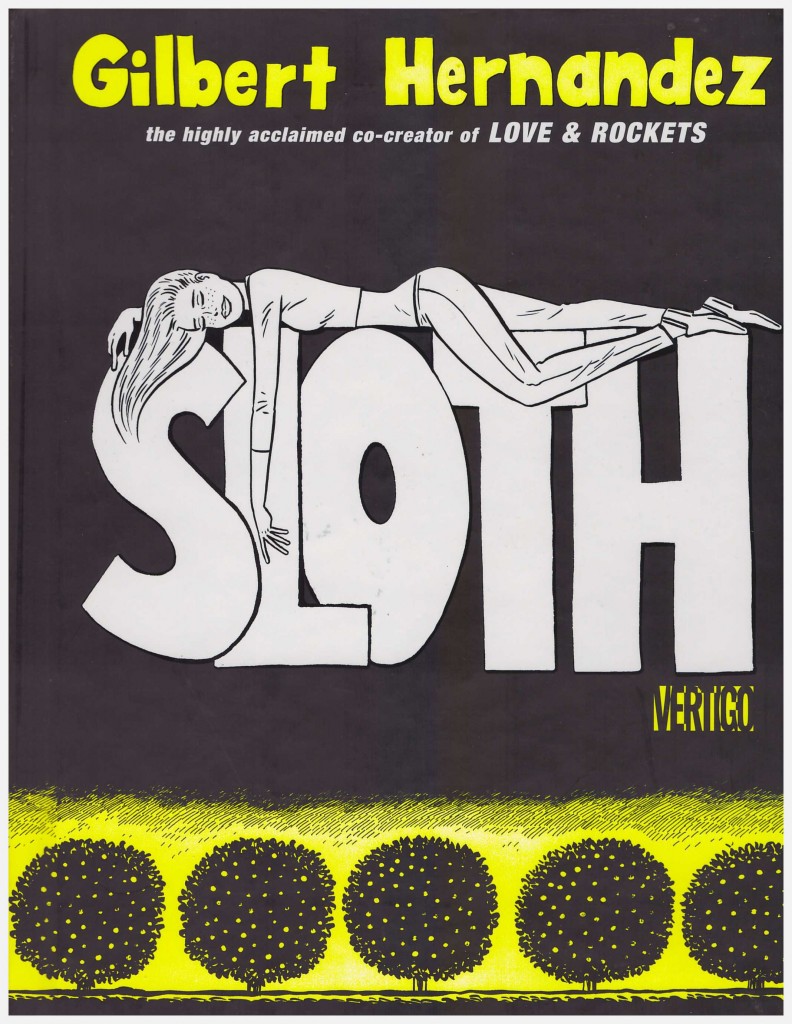

After two decades of plotting his stories for serialisation in Love and Rockets, this was a first opportunity for Gilbert Hernandez to construct an original narrative to be presented as a complete longer story without having to consider episodic breakdown.

Although it’s hardly apparent for much of the novel, Sloth considers the roles we have in life and whether they’re carved in stone. As such it’s a sort of Schroedinger’s Cat of the graphic novel world. It’s also apparent that David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive was very much in Hernandez’s mind when he set about constructing Sloth.

Yes, Sloth is a construction, bisected by a brief dream sequence after which everything is thrown into the air. It begins with the teenage Miguel awakening precisely a year after slipping into what may or may not be a self-induced coma. The only lingering effect is that he’s now unable to move at anything other than a very slow pace, an irony as his band is named Sloth. Beyond some taunting, life rapidly returns to normal for Miguel. He’s able to pick up again with his girlfriend Lita, but his new sedate pace of life is reflected in his approach to music, which is beginning to rankle with the other band member, Romeo.

While Miguel was comatose Lita and Romeo may, or may not, have started a relationship, but she has become interested in inexplicable events and local legends. Central to this is a lemon grove said to be haunted by a goatman who guards the dead but will switch places with anyone who spots them. Lita, Miguel and Romeo visit the lemon grove, have a strange experience and return with even stranger video footage.

To this point Sloth sucks in the reader with the hints of mystery hanging over what’s otherwise an endearing portrayal of teenage hesitancy and growth populated by a distinctively characterised supporting cast who drift into the narrative then out again.

The reason for this is revealed as Sloth enters its second phase, in which everything changes and the cast fall into new roles. This is initially disturbing, but rapidly offers new insight into those we’ve met before. There is, however, no neat explanation for those who prefer their stories cut and dried.

Hernandez’s art is defined by his usual use of large areas of black ink for atmospheric effect, but his characters occasionally display an uncanny vividness, as if they themselves are on occasion possessed. Moments of serenity beyond a bed are few.

The lack of resolution isn’t the failing it might be for a less accomplished storyteller. Hernandez is extremely skilful at building character via small moments, and this observational intensity familiar to readers of his Palomar and Luba material serves him well here. But this is a halfway stage between that approach and the playful and surreal work most effectively displayed in Fear of Comics. The engaged reader will find themselves mulling this over for some while after closing the covers.