Review by Ian Keogh

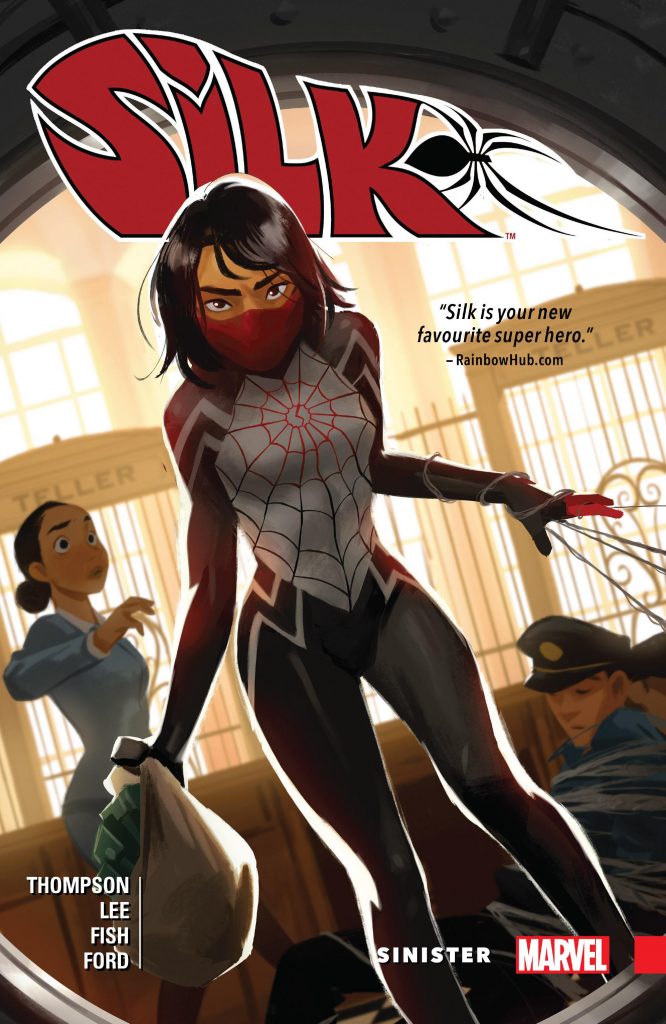

The Life and Times of Cindy Moon introduced an appealing new superhero with more obviously vulnerable side to her. Robbie Thompson’s modern day extrapolation of the Peter Parker/Spider-Man duality continues here with little change from the first book despite the end of the world occurring between volumes. In that first book the criminal Black Cat offered Silk a job, and for reasons of her own she’s signed up, which complicates her life still further, at the least burning up the hours so she has little time for sleep.

That’s one of several nice individual touches Thompson throws in while constructing a relatively unique superhero comic. Another is that Silk sees a therapist. This is understated, but the conclusions reached have an effect on her personality and the way she deals with the world. As he has been for so long in Spider-Man, J. Jonah Jameson, now back in a newsroom, is a compelling character for all his ignorant bluster. Also interesting is the way Thompson tells his stories. They involve different voices piecing the elements together, some portions told in hindsight via conversation. It’s all very smooth, but must take a lot of planning.

Not everything works. A major clue as to Silk’s missing family lies with the Goblin Nation, who’re abducting young men and transforming them into super-powered thugs. It might be different individuals, but the similar nature of their powers means that fighting assorted members of this Faginesque sewer-living society is repetitive. They long outlive their welcome, but at least avoid being still intact to plague Silk in the following The Negative (although before then there’s a sidetrack in Spider-Women, which is fun, but not essential to the main continuity).

Stacey Lee defined Silk so well over the opening volume that it’s a shame she only illustrates the opening chapters here. Tana Ford was the better of the two guest artists then, and draws the bulk of this in her decidedly odd style. It’s loose, and sometimes extremely delicate, still bringing to mind Sam Kieth in places, but character-rich and often exotic. Veronics Fish’s two chapters have Lee’s scratchy approach and her diagonal panels, but the odd viewpoints and sometimes even stranger exaggerations don’t work as well.