Review by Frank Plowright

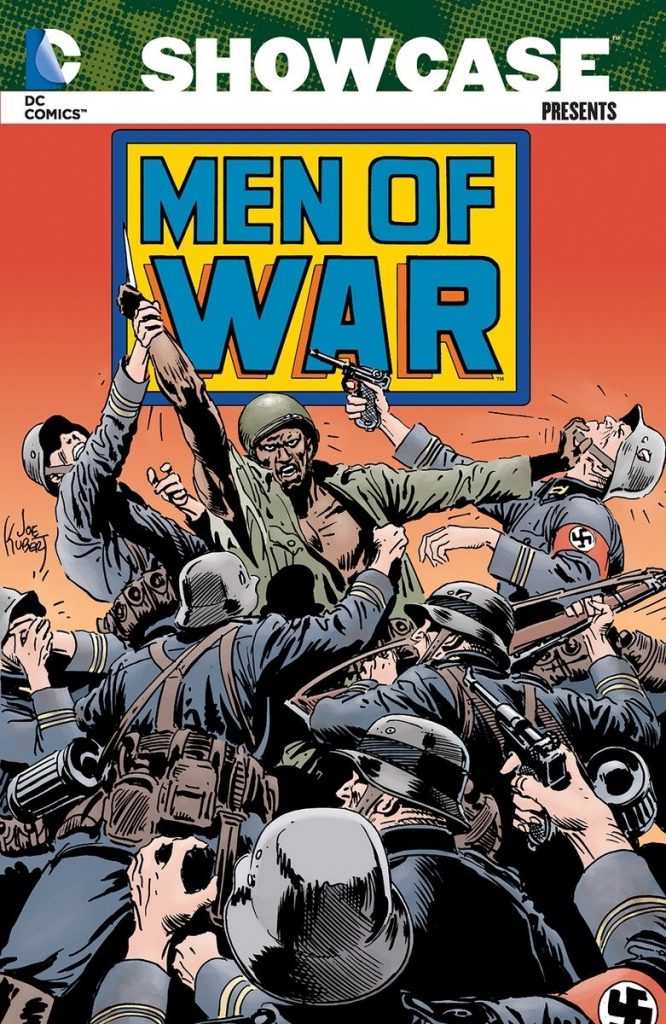

The Showcase Presents line has ostensibly the same purpose as Marvel’s Essentials publications in supplying the company’s back catalogue in affordable black and white on pulp paper. What makes the DC titles more desirable, though, is their reprinting material otherwise unavailable in book form. This is the case for Men of War’s short 1970s run.

In 1977 DC considered the future of war comics was to feature continuing characters, so four of them rotated in short stories, accompanied by a couple of tryout strips. Ulysses Hazard, Gravedigger was seen as the breakout feature. As introduced by David Michelinie, he’s a World War II G.I. angry at his talents being wasted in the Burial Corps because he’s African American, so forces the issue and becomes a specialist in missions needing a single capable man behind enemy lines. The fundamental flaw of how obvious an African American would be in wartime Europe is never addressed. Michelinie uses the language of the times in showing what Ulysses endures, dropped when Roger McKenzie takes over, but neither produce anything memorable from the premise. The later stories are written by Jack C. Harris, who still supplies the wartime adventure thrills, but at first with more thought behind them than a gung-ho soldier performing an impossible mission. The majority of the feature is drawn by the team of Dick Ayres and Romeo Tanghal, who’re astonishingly inconsistent. For every nicely laid out page as per the sample art, there’s a page that looks as if barely any time was spent producing it. However, what began as a strip with a point to make is largely ignored by Harris, whose contributions drop to barely believable sensationalism.

Men of War also found a home for Enemy Ace. Robert Kanigher had been writing about the World War I German flying ace sporadically since the 1960s, and his complete catalogue to the 1980s is collected in a separate Showcase Presents volume. Consulting that shows Kanigher coasting for these stories, revisiting old plots and scenarios, only briefly displaying why Enemy Ace is so highly regarded. Howard Chaykin’s slashing lines are a surprisingly good fit, and he draws this collection’s best Enemy Ace story of Hans Von Hammer’s family standard being stolen, and the legend about his destiny should that ever happen.

Despite Jerry Grandenetti’s mad-eyed and exaggerated people, the most consistently engaging feature is ‘Dateline: Frontline’, in which Cary Burkett has an American reporter in Britain, North Africa and Russia during the 1940s. There are only nine stories, but Burkett consistently creates interesting elements to hang them round, be that wartime censorship, a cowardly hero or the horrors of Leningrad, and he supplies enough action also, just not always the traditional war combat. Occasionally Grandenetti also comes through as per the memorably haunted face on his sample page.

Grandenetti also draws ‘Rosa’, a spy during the 1860s and 1870s, first during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, then during a Mexican revolution in which his origin is related. Confounding expectation, Rosa isn’t a woman, but despite a sense of honour he lacks charisma, Grandenetti’s pages are untidy and unclear in places, and Paul Kupperberg’s plots are high on coincidence.

Men of War is very much of its era, and war story standards have been raised considerably since. Burkett’s plots are the only ones with anything to recommend them, which makes this for completists only.